Write! Draw! Move!: Investigating the Effects of Positive and Negative Self-Reflection on Emotion through Self-Expression Modalities

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3716553.3750798

ICMI '25: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Canberra, ACT, Australia, October 2025

Emotional self-expression positively impacts people's well-being by reducing stress and contributing to overall well-being. As digital mental health interventions become more prevalent in assisting graduate students with stress management and emotional awareness, it is important to understand how self-expression modalities can be effectively integrated. We conducted a study in which graduate students reflected on a positive experience and a negative experience, separately through three self-expression modalities (visual art, writing, and movement). Our results showed that negative reflection elicited a sense of relief as it felt calming and therapeutic. The visual and movement modalities helped participants express themselves creatively, whereas writing pushed them to face their emotions head-on. Our findings contribute to the multimodal interaction community and the field of HCI toward developing intelligent, affective multimodal digital technologies to encourage enhanced well-being through emotional and creative expression and reflection for graduate students.

ACM Reference Format:

Golnaz Moharrer, Kavya Rajendran, Rowena Pinto, and Andrea Kleinsmith. 2025. Write! Draw! Move!: Investigating the Effects of Positive and Negative Self-Reflection on Emotion through Self-Expression Modalities. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (ICMI '25), October 13--17, 2025, Canberra, ACT, Australia. ACM, New York, NY, USA 10 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3716553.3750798

1 Introduction

Digital self-reflection tools provide the space to recognize and understand emotions and gain cognitive insight and personal growth by developing interpersonal skills, building confidence, and sustaining motivation [4, 25, 45]. Graduate students are a population at high risk of mental health issues as they face more struggles with work-life balance, mentorship quality, and research and job demands [17, 26, 38]. Emotional awareness is particularly crucial for them as it enhances academic performance while reducing counterproductive rumination, and therefore may enable more effective navigation of their unique challenges [20, 62]. Ineffective stress and emotion management can deplete the emotional, social, and psychological well-being [2] of graduate students, leading to burnout and potentially causing them to drop out [19]. While there are a number of self-reflection tools aimed at stress management, there are few specifically geared toward graduate students [52]. Furthermore, the majority of tools that exist for the general public employ text as the most common modality. Research has shown that movement-based activities positively influence the emotional and mental well-being of graduate students [42]. Integrating mindfulness with visual art has also been linked to a reduction in graduate students’ stress [70] by reducing mental pressure [51].

While psychology research shows enhanced emotional well-being and stress relief following dance and other forms of body movement, these studies are limited to individuals experienced in dance and other physical activity [44]. There is a need to explore non-verbal expression modalities [61] and to integrate support for multimodal self-expression within digital self-reflection tools [69]. Moreover, technology-mediated reflection often focuses on negative aspects of life experiences, risking a rumination cycle that results in maladaptive emotions for users [16]. Research recommends that technologies integrate positive, embodied, and tangible reflection to regulate emotions and enhance mood [13, 29], an area that is still underexplored.

We conducted a study to address the following two research questions: RQ1 - What are the effects of self-expression modalities on graduate students’ emotions? and RQ2 - To what extent do positive and negative self-reflection affect self-expression in different modalities? Graduate student participants engaged in self-reflection through three modalities separately—traditional journaling, visual art, and body movement—in two conditions, reflecting on a positive experience and reflecting on a negative experience. The goal is to understand students’ perspectives on the different modalities and how positive and negative reflection impacts their emotions in each modality to inform the future design of digital self-reflection technologies. The results revealed differences between the emotional impact of positive and negative self-reflection experiences: participants embodied intense positive emotions while reflecting on positive experiences, and felt emotional relief after reflecting on negative experiences. While the writing modality helped them confront their thoughts and feelings, the more embodied modalities of visual art creation and movement expression helped participants engage with their emotions and focus on the activity at hand. This research contributes to Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) by exploring emotional experiences during verbal (written) and non-verbal (visual art and movement) self-reflection modalities among graduate students, offering insights for designing emotionally intelligent, multimodal technologies that encourage self-expression, increase self-awareness, and support the emotional well-being of users over time. Future research could explore strategies to enhance the reflection experience by providing structured guidance and making movement-based modalities more intuitive.

2 Related Works

2.1 Self-Reflection and Emotional Expression

Self-reflection is understood as a mental process of examining inner experiences to evaluate thoughts and emotions, leading to increased self-awareness and understanding [25, 54]. For graduate students, self-awareness of their emotional state and mindset is crucial for navigating the unique challenges of their academic journey [17, 20, 62]. While most models of self-reflection emphasize recognizing and addressing difficulties, recent research suggests that focusing exclusively on problems may inadvertently reinforce negative emotional states and rumination [16]. Expanding the scope of reflection to include positive experiences can foster resilience and emotional growth [29]. Positive psychology offers a complementary perspective, highlighting the benefits of focusing on positive self-reflection of past experiences. This approach is linked to lower negative affect and increased positive affect, described by Fredrickson and Joiner as an "upward spiral" of emotional well-being [22]. Research suggests that reflecting on positive emotions related to upsetting events can be as therapeutic as expressing negative feelings [55]. This aids in emotion regulation [37], promotes perspective shifts, and fosters openness to new experiences [53].

Since emotional self-expression can reduce stress, offer valuable insights, and contribute to students’ academic development [32, 40], innovative approaches where users connect with challenges and emotions from multiple perspectives exemplify the benefits [31, 67, 68, 69]. For instance, SelVReflect [69] offers active voice-based guidance in a virtual reality setting, providing users with a space to freely express themselves and reflect on personal challenges. Similarly, MoodShaper [68] enables users to manage negative emotions by creating personalized virtual environments to incite emotional regulation and resilience. Recent advances in ambient biofeedback systems have inspired tools like DeLight and MoodLight which use physiological data, such as heart rate variability, to adjust ambient lighting based on users’ arousal levels. These subtle environmental cues promote emotional awareness, self-regulation, and well-being [60, 72].

2.2 Verbal and Non-Verbal Self-Expression Modalities

Research shows that verbal expression, particularly through expressive writing [74], can effectively reduce academic stress and negative emotions [3, 30]. Studies show that students who regularly engage in expressive writing experience a gradual reduction in stress and an ability to articulate emotions in writing rather than through speech [3]. Expressive writing enhances emotional awareness and cognitive processing. Research by Maslej et al. indicates that it fosters analytical rumination and causal exploration, aiding problem-solving in undergraduates [43]. Additionally, research suggests that expressive writing contributes to subjective well-being by increasing happiness and life satisfaction, as students who engage in this practice report greater emotional clarity and self-understanding [10].

Visual art provides a powerful outlet for stress relief. In Yamamoto et al.’s study, graduate students used "Stress Monsters" to externalize their stress, which helped them understand and manage it through strategies like control, detachment, and normalization. [52]. Mols et al.’s study explored how visual and other self-expression modalities influence reflection and fit into daily life. Their in-the-wild deployment of three interactive prototypes – Balance (audio modality), Cogito (textual modality), and Dott (visual modality) – revealed that visuals and text were more easily integrated into daily routines, with visuals supporting deeper emotional expression [47].

Movement is a powerful form of self-expression, with research showing it both reflects and regulates emotions through a bidirectional link. [56]. Shafir et al. further explored this connection, identifying specific movement characteristics associated with particular emotions, demonstrating how intentionally choosing or avoiding certain movements can embody happiness and manage negative emotions like anxiety [57]. While technologies like the Affective Diary capture "bodily memorabilia" through sensors mapping movement and arousal levels, these technology-driven interpretations can sometimes be severed from the user's actual emotional experience [61]. This suggests that intentional self-expression through body movement, rather than reflecting on passively captured data, might be more beneficial for embodying emotions.

As demonstrated by Shafir et al. [56] and Mols et al. [47], more research is needed to compare modalities, especially expression through movement. There is also a need to focus on positive reflection, rather than solely on negative experiences. To address these gaps, we investigated self-expression in different modalities and the impact of reflection on both negative and positive experiences. This work aims to inform the development and implementation of digital technologies that better support the specific needs of graduate students in managing their emotional well-being.

3 Method

3.1 Experimental Design

We implemented a counterbalanced within-subjects experimental design with two conditions: reflecting on a positive experience and reflecting on a negative experience. Task instructions were minimal and explicit examples or prompts were not provided to ensure participants considered their own interpretation of reflecting on positive and negative experiences. To encourage participants to be as open as possible, they were asked to reflect on experiences that they were comfortable sharing and expressing through each of the three modalities, i.e., writing, visual art, and body movement. The order of modalities was randomized to minimize bias [8].

3.2 Study Setting and Procedure

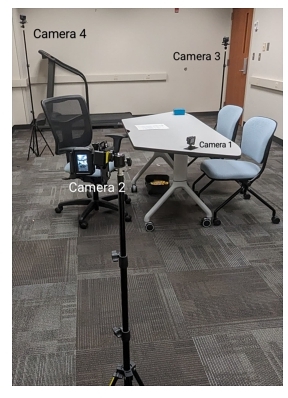

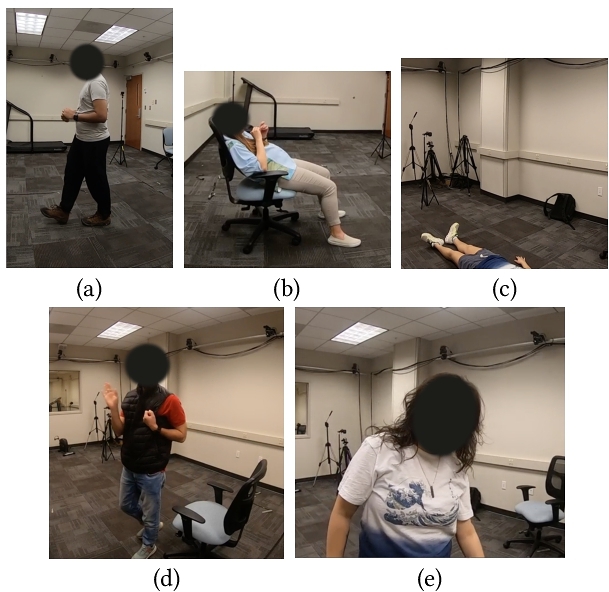

The study was conducted in a large user studies lab with a separate observation room with a one-way mirror. A small table and chairs were placed in the center of the room. A GoPro camera was placed on the side of the table facing the participant. Three more GoPros were placed at different distances from the participant to capture different angles of the entire scene (Fig. 1).

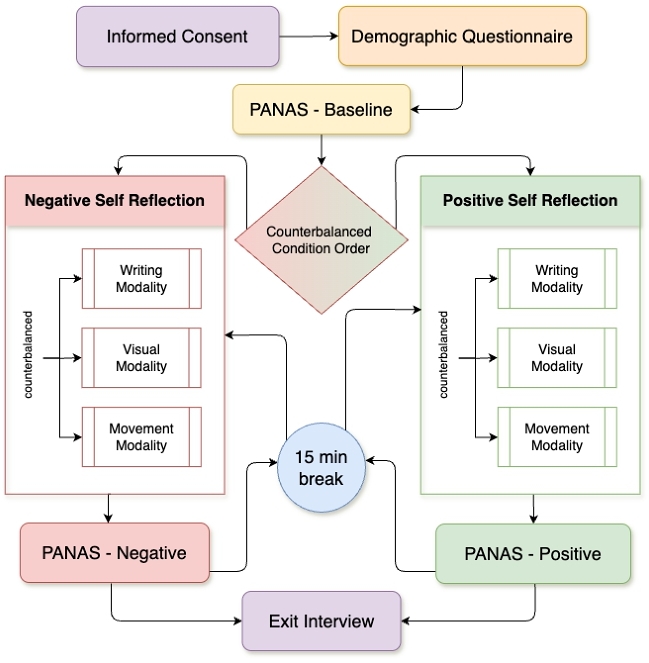

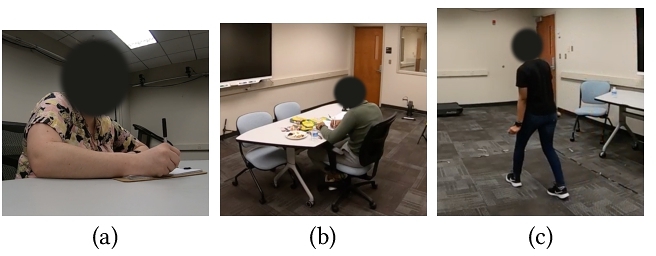

Fig. 2 illustrates the counterbalanced study design. Upon arriving at the lab, participants reviewed and signed the consent form. Participants then completed a demographic questionnaire and the PANAS questionnaire [15], after which they engaged in positive and negative self-reflection separately (i.e., two conditions) through each of the modalities (Fig. 3).

After participants completed one condition (i.e., the positive or negative experience), they completed the PANAS questionnaire for a second time. Participants took a 15-minute break between conditions, during which we provided snacks. We intentionally avoided providing sugary snacks or caffeinated beverages that could affect their mood for the second half of the study [66]. After completing the second condition, participants completed the PANAS for a third time. The session ended with a semi-structured interview about participants’ experiences. To mitigate potential negative emotional effects of ending the study on a negative experience [16], we offered participants additional time to reflect on another positive experience through their preferred modality. This was not recorded and was entirely optional.

3.3 Participants

We recruited participants via emails sent to their university accounts and snowball sampling [48]. Prospective participants completed a Google form to determine eligibility. Participants were required to be graduate students at our university, between 18-35 years of age, and willing and able to express themselves through body movements. We sent the consent form to eligible students to review ahead of the session. Fourteen graduate students consented to participate (9 women, 5 men), of which 8 were majoring in Human-Centered Computing (3 PhD and 5 MS), 3 in Engineering Management (MS), one in Computer Science (PhD), one in Data Science (MS), and one in Biology (MS). Participants self-reported their ages according to ranges: 18 - 23 years (n=2), 24 - 29 years (n=11), and 30 - 35 years (n=1). The majority of participants were Asian (n=11), two were Middle-Eastern, and one was White. The single study session took an average of 1 hour and 52 minutes to complete (± 29 mins). The study was approved by the university's institutional review board.

3.4 Data Collection

3.4.1 Video Recording. Four GoPro Hero7 Black cameras recorded audio and video of the sessions.

3.4.2 Questionnaires. Participants completed three questionnaires. A demographic form collected information about participants’ age, gender, and education. The PANAS [15] was administered three times. It contains 20 different emotional descriptors: ten positive, e.g., Interested and Proud; and ten negative, e.g., Guilty and Afraid. Participants rated the general extent to which they felt each of the emotions according to a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Very slightly or not at all) to 5 (Extremely). The PANAS is scored by summing the ratings for positive emotion descriptors and the ratings for the negative emotion descriptors separately, yielding two separate scores.

3.4.3 Semi-structured interviews. We conducted semi-structured interviews at the end of the entire session to understand participants’ emotions and overall experience during each modality in each condition. Questions asked included “Describe the emotions you experienced during each modality” and “Which modality (writing, visual art, movement) did you prefer for self-reflection?” (Refer to the Appendix).

3.4.4 Artifacts. Participants were given ruled paper and pens for writing modality, and more art supplies were provided for visual arts, including markers, colored pencils, and magazine cutouts. In the movement modality, they silently expressed emotions through mime or dance, recorded by GoPro cameras. While no props were explicitly provided, some used the room's furniture for expression.

3.5 Data Analysis

3.5.1 Qualitative Analysis. We performed inductive qualitative analysis [64] to understand the emotions experienced by participants while reflecting through each self-expression modality in the positive and negative reflection conditions, partially addressing both of our research questions. Interviews were transcribed using Otter.ai and error-corrected by the first three authors. The corrected transcripts and photos of participants’ writing and visual art artifacts were then uploaded to Dovetail for collaborative thematic analysis. A codebook was established by the first three authors, who open-coded two participants and met virtually to resolve disagreements until consensus was reached. Example codes include writing is accurate, writing is for analyzing self, happy during visuals, cutouts inspire creativity, movement to recall memories, movement feels awkward, and benefits of self-reflection. The remainder of the transcripts were then divided among the first three authors who independently coded the data. Once coding was complete, we met again in three virtual sessions to resolve any disagreements, collapse codes, and identify themes. Artifacts were selectively reviewed to add narrative. The following four themes were identified: Different Modalities Allow for Different User Experiences; Happy in Positive and Relaxed in Negative; Beauty Lies in the Processing and Analyzing; and Make Creative Self-Expression Easier.

3.5.2 Quantitative Analysis. To investigate overall differences between negative and positive reflection conditions, we conducted two separate one-way repeated measures ANOVAs, one with the PANAS positive scores and one with the PANAS negative scores to determine whether there were statistically significant differences across the three times it was administered (Fig. 2).

4 Results

4.1 Different Modalities Allow for Different User Experiences

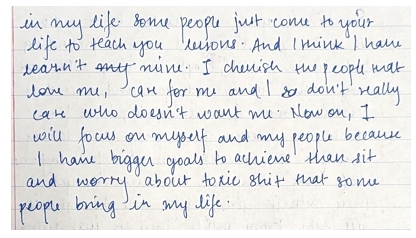

4.1.1 Let Negative Emotions Go by Writing Them Down. Writing was the top-ranked modality. Many participants preferred it because it was most familiar, primarily due to their previous journaling experience, as well as the space it provides to express and process their thoughts, emotions, and experiences. : “[I prefer] writing because I like to write. I find it a lot easier to write down my thoughts and to process what I- putting through what's going through my head through writing. So I just I enjoy it. It's a lot more comfortable for me just to write what I'm feeling.” – P03.

Participants were also able to vent their emotions through writing, especially negative emotions, as P08 stated, “About the writing section – that was interesting because I noticed that I have more, more interested to write my negative like feeling than positive, really. I started just nagging like I just complaining about everything.” Reanalyzing their emotions gave participants a sense of control and calm; for instance, P12 organized their negative thoughts while writing about an anger-inducing experience: “It made me realize that while writing and then at the end of the writing, I was like, I was very calm; my tone changed suddenly while writing.” While P06 preferred writing over the other modalities, they countered that “If I write, I'm always afraid that, oh, someone might read it. If I do something, I, I feel like a little embarrassed like, oh, what if someone sees me? I'll always be thinking about that.” This raises the important, ever-present issue of privacy concerns with digital tools, particularly when sensitive data around emotions is involved.

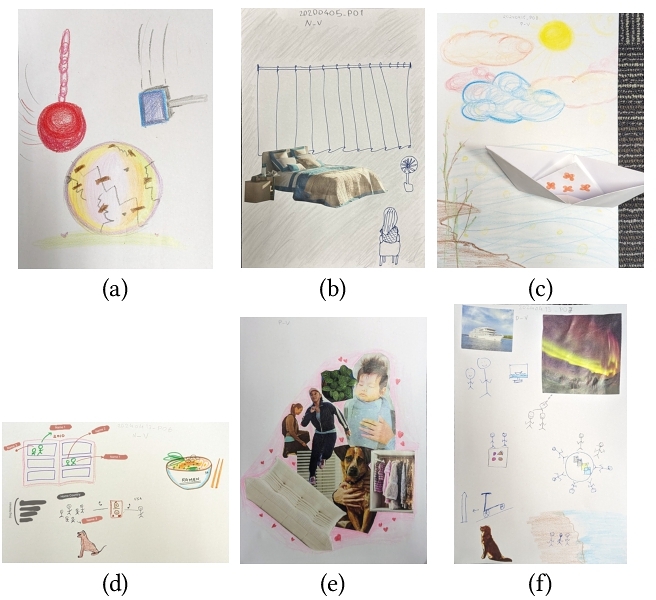

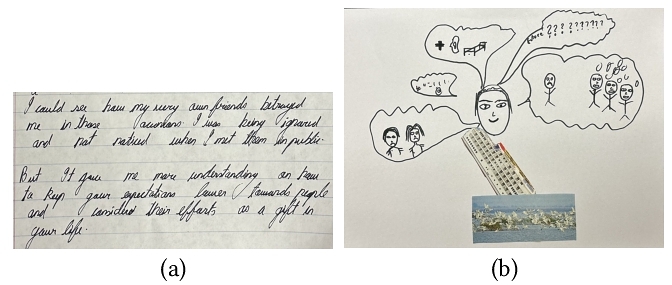

4.1.2 Collaging my Emotions Creatively Makes Me Smile. Visual art was the middle-ranked modality. Many participants enjoyed reflecting through the visual art modality as they felt “happy,” “calm,” "meditative," “amusement,” and “freedom,” irrespective of their previous experience with visual self-expression. The visual medium provided an opportunity to depict their indescribable feelings symbolically as noted by P03, “Some things are harder to describe. Yeah. You know, sometimes you just want to draw it.” This participant sketched the artifact in Fig. 4(a), in which they colored a cracked stone with band-aids being attacked by a hammer and a wrecking ball to depict a difficult time they had experienced. Integrating cutouts into drawings (Fig. 4(b) and (f)) also boosted creativity and engagement as revealed by P02: “It (the overall experience) was interesting. Especially with the cutout papers that I didn't think I can make anything with them. But then I became the most creative with those, I guess.” For P12, the cutouts (Fig. 4(e)) helped them explore their emotions: “And in the visuals part, it was like I was discovering the emotions myself when I was looking at the pictures. So the ‘Oh, with this I can do here. I can do that.’ Like, I was feeling it while I was looking at the pictures.” Collaging, particularly, was “very relaxing” for participants as P10 described, “I feel like the collaging is just like a little bit more meditative, almost like you're just kind of like drawing and gluing things. And maybe you have like an initial thought, that's why you're making it. But at a certain point, it's just kind of like, a nice, like meditative activity.” The tangible aspect of the visual art modality appealed to P08 (Fig. 4(c)), "I would choose drawing. Drawing or, like making something. It's not only about drawing. Just like I made the boat, it can be just making something just doing something with my hand." One participant, P05, who was reluctant to write details during their negative condition, preferred the visual modality as an abstract form of self-expression, “The second (visual modality) was somewhat helpful because it's a bit more abstract. So for some reason, it's a bit more approachable. Because you don't really need to go down into the details.” Similarly, referring to the negative reflection condition (refer to (Fig. 4(d)), P09 highlighted that “For at least the negative drawings, it would only make sense to someone, make sense to someone if they were to read what went with it kind of thing, like have a text.” Quite a few participants said they enjoyed writing and drawing equally and wanted to combine them in future reflections.

4.1.3 Go with the (Emotional) Flow of Your Body Movements. Body movement was the lowest-ranked modality. Participants reported feeling “shyness,” “uncomfortable,” or “awkward,” particularly because this was the most unfamiliar modality for many of the participants. Thus, they were unsure of how to physically express their emotions, as P12 said, “So for the movement, as I said, I was a bit shy. I mean, I don't, I couldn't figure out, how do I express it in movement.” Similarly, P03 said, “I just, I've never tried to express myself through movement. This was probably one of the first times so that was awkward, but fun. Not awkward like I don't know if I'll ever want to do it again. But awkward.” Participants like P02 were vocal that movement was their least favorite modality, “The movement was very weird for me. It might be, maybe, that I'm not comfortable - just using my body as an instrument.”

Although the novelty of the modality brought discomfort, for some, it was due to camera shyness or the knowledge that they were being recorded for the study. However, other participants were less shy and anthropomorphized the cameras as they mimed for or interacted with them during the movement modality (Fig. 5(d) and (e)).

On the other hand, other participants felt more positive about the movement modality, such as P14 (Fig. 5(a)), enjoyed it for the sense of freedom they felt it prompted while allowing their emotions to flow through their bodies: “So I would say that and the movement itself that the ability to just move around and just if you don't like something, you can just shake that thing off your body like that. That ability of just the just physically shaking something off was was nice feeling in that moment.” This physicality provided a unique reflection experience as P03 added, “I think maybe trying the movement one would be more fun, like, be more expressive, more active. I think that would be fun. Just because, you know, writing and drawing, you're sitting all the time. And sometimes you need to be active and sweat and get the blood pumping and feel better too.”

4.2 Happy in Positive; Relaxed in Negative

The participants noted a stark contrast between reflecting on positive and negative experiences. P02 explained the dichotomy between the positive and negative conditions as, “Thinking about the negative one make, make me like more sad but thinking about the positive experience made me more proud and strong.” Participants reported the positive reflection condition to be “exciting,” “interesting,” and “easier to express” while they recounted various interlinked positive moments, such as P06 who expressed a “truly happy” memory with “exhilarating” nostalgia. P07 recalled multiple happy instances, “First I thought I will have one positive like experience, but I started like writing many positive experiences. I didn't know. Like, it kind of made me excited.”

Although some participants felt sad or frustrated during the negative condition, the majority described feeling a sense of emotional relief and calmness by the end, as explained by P07, “The negative experience like start, like putting all the excitement down. Yeah. And I'm now like, in a calm state.” P08 expressed feeling more “concentrate in the second study [negative self-reflection condition], rather than the [positive self-reflection condition]. And that was interesting because after [negative self-reflection], I felt more calm and how to say something like when you release your stress, right? Like that.” This corresponds with the fact that only one out of the seven participants who ended the session on the negative condition chose to reflect on an additional positive experience. Participants also felt they gained valuable insights from evaluating their behavior through new perspectives, as illustrated in Fig. 6 and explained by P04, “And in the negative ones, I didn't give quite a thought about what happened to me. It was more about how I am as of now because of that, and how we can just learn to strive in a positive manner, and how it actually made a significant impact in my life.”

4.3 Beauty Lies in the Processing and Analyzing

Engaging in self-reflection, regardless of whether it is positive or negative or the modality through which it is expressed, provided space for participants to process and analyze their emotions. Negative reflection, in particular, helped participants understand their past reactions and aim to improve future responses, adding to personal growth as noted by P04, “I would prefer more on my negative modality (over positive reflection modalities). Because that's when you can see what happened and why you were reacting in a way back in the time” (Fig. 6). Participants gained positive insights from negative reflection, potentially shaping future actions. Writing was especially helpful, as P14 explained, “For writing, I would say it's a, it's a good way of um seeing like, like like having a kind of a log of all of your thoughts would be the right way of saying it. Like you can, you can log every single thought of any emotion that you're having and you can check them: how right they are, how wrong they are and stuff.” For example, P12 recognized self-love and valuing supportive relationships as a transformative learning experience (Fig. 7).

Many participants also recognized the importance of positive reflection, emphasizing that it leads to personal growth. As explained by P01, “What I learned was, I reflect a lot on negative stuffs. But I do think I have to reflect a lot on positive things also, because you, I can't take it for granted. And it's like, you know, sometimes people go wrong on positive things also. So I learned that I have to reflect on my positive stuffs also, and see how my character has improved.” P04 expressed similar sentiments, “In positive thinking, it was more about looking out and thinking more about what I had back in the days and then how I could have enjoyed it more and live my life more better. And negative, it was like how I can be inspired with that and take it to my future lives.”

4.4 Familiarity Breeds Comfort and Appeal

Participants often identified the most familiar modality as the easiest or most comfortable for engaging in self-reflection. P03 exemplified this contrast regarding writing and drawing, specifically, “I do write and I draw on my hobby. So those two were like, both for the negative and positive, it felt more natural to me to write and draw because that's what I do.” However, referring to the less familiar modality of movement, P03 described the experience as “one of the first times - so that was awkward but fun.”

Familiarity also shaped how participants handled positive or negative experiences. Most found expressing positive experiences easier, like P05 who stated, “it was easier to express positive emotions than the negative emotions.” However, a few participants, like P08, who were not used to openly sharing positive experiences, found positive self-reflection harder, “Most of the time, I never share my happiness. Okay, if something would happen to me, I never share. So that's why maybe the I'm, that's not a reason. I'm just thinking. That's maybe why I didn't write anything in my positive emotion because I don't know. I never learned how to express my positive emotion.” Sharing their experience with friends or any support system was also brought up by quite a few participants who went on to suggest integrating a conversational space: “I don't know it's my preference, but I prefer somebody to talk to. Like, I'm kind of person who express from my words, like talk and it comes out, otherwise, it's pretty hard to express" – P04.

Repetition of reflection through varied mediums provided emotional context and a deeper understanding. P14 appreciated “exploring the same memory again” through multiple modalities. Participants such as P03 also suggested including a tutorial as well as props to interact with to make the movement modality easier to approach:

P03: Maybe showing them a video of what it could be like, for people that don't know what it means to express yourself through movement. Or it could you can give them a prop, very neutral prop, like a piece of papers and kind of just fumble around with a newspaper, a ball, give them something to get going. The whole recognition recall, it's easier to- Researcher: Maybe like the cutouts we had for visual? P03: I think the cutouts too would be really good. Be it something as simple as just like clicking a pen to just kind of get them moving.

A few participants desired the addition of music, as highlighted by P06, “When I was doing mime, I was ok; but when I was doing the dance thing, I was missing music,” and further emphasized by P10, “If there's music, Sure! Yeah, I'll like move and dance. But yeah, it's like if there's no music, just kind of like what am I doing?”.

Overall, prior experience, familiar objects, and repeated practice enhanced comfort and creativity in different modalities in the positive and negative reflection conditions. This highlights opportunities for digital technologies to incorporate familiar elements or leverage metaphors in their design. Meanwhile, offering new experiences, such as self-expression through movement or positive reflection, can provide fresh perspectives that support well-being.

4.5 Statistical Analysis

4.5.1 PANAS. The ANOVA results comparing the positive and negative PANAS scores separately are presented in Table 1. The ANOVA conducted with the positive PANAS scores showed moderately significant differences across the three times it was administered, $F(1.294, 16.828) = 3.354, p = 0.086, \eta ^2_p = 0.205$. Post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant increase in positive scores from the baseline PANAS (M = 31.50, SD = 5.653) to the positive condition PANAS (M = 34.29, SD = 6.170) p = 0.044. These findings show that positive affect significantly increased after positive reflection, while no change occurred during negative reflection, regardless of its order. This may be due to positive emotions expanding cognitive and emotional resources, sustaining mood improvement [22].

| Positive PANAS | Negative PANAS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison | Diff | SE | p | Diff | SE | p |

| Baseline vs Pos | -3.02 | 1.09 | .044 | 4.50 | 1.49 | .029 |

| Baseline vs Neg | 2.21 | 2.25 | 1.000 | -1.64 | 2.37 | 1.000 |

| Pos vs Neg | 5.29 | 2.52 | .168 | -6.14 | 2.19 | .044 |

The results of the ANOVA conducted with the negative PANAS scores revealed statistically significant differences across the three times it was administered, $F(2, 26) = 4.824, p = 0.017, \eta ^2_p = 0.271$. Post hoc analysis revealed that negative scores significantly decreased between the baseline PANAS (M = 16.50, SD = 6.273) and the positive condition PANAS (M = 12.00, SD = 2.038) p = 0.029 while they significantly increased between the positive condition PANAS and the negative condition PANAS (M = 18.14, SD = 9.502) p = 0.044. Negative affect decreased significantly after positive self-reflection and increased when shifting from positive to negative reflection, with no significant change when negative reflection was the initial condition. This suggests positive reflection may help reframe negative thoughts, while switching to negative reflection reverses the effect [65].

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

In this work, we contribute to the design of future self-reflection technologies by examining how each of the three self-expression modalities—writing, visual art and movement—impacts graduate students’ emotions (RQ1) and the differences apparent under the negative and positive reflection conditions (RQ2). In the remainder of the section, we discuss our findings in relation to the current literature, along with limitations and future.

5.1.1 Write! Draw! Move!. The highest-ranked modality for self-reflection was writing, which facilitated emotional release by allowing participants to express their thoughts and analyze their experiences objectively. This aligns with research supporting self-reflective journals as a psychotherapy tool for enhancing emotional awareness [18, 49]. Participants felt a sense of calm after exploring and unburdening their feelings, akin to the anxiety-reducing effects of expressive writing through emotional processing [3, 28, 71].

In the visual art modality, participants felt happy just engrossing themselves in the activity, irrespective of whether they were reflecting on a positive or negative experience [34]. This aligns with prior research results demonstrating that participants experienced short-term happiness and arousal improvement while painting [14]. The coloring materials and magazine cutouts also play a part in relieving negative emotions and engendering immediate child-like joy in the moment [14, 47, 63]. The modality was regarded as a meditative activity, aligning with research in art therapy, well-known as an effective mental health intervention for mood disorders and older adults suffering from dementia or schizophrenia [59].

Participants often felt awkward in the movement modality due to its unfamiliarity and the absence of guiding prompts during the task. However, this was intentional in the experimental design as we aimed to understand the boundaries of embodied reflection through each modality toward designing and developing a digital reflection system. Although most participants were less familiar with the movement modality, they attempted some sort of physical movement which allowed them to be open to different perspectives of their experience [35]. Similar to dance therapy, they embodied emotions relating to their experience before cognitively processing them [36]. Moreover, minimal instructions encouraged exploration, supporting findings that unrestricted movement nurtures creativity [23].

5.1.2 Take the Good within the Bad. Negative self-reflection facilitated emotional release and relaxation for students while positive self-reflection evoked excitement and nostalgia, with participants experiencing a snowballing effect, where recalling one memory led to others, intensifying positive emotions [43, 55]. One-way repeated measures ANOVAs confirmed significant increases in positive affect and decreases in negative affect when participants engaged in positive reflection first. This aligns with positive psychology findings that revisiting pleasant experiences enhances mood and well-being [39]. This cascading recall effect holds promise for mental health tools designed to improve mood and reduce stress [22]. Repeated reflection on the same negative or positive experience further improved emotional and cognitive processing as they confronted it through a new medium each time [11]. Participants also tended to end their negative reflections on a positive note, showing potential for transformative critical reflection [6].

5.2 Design Implications for HCI

5.2.1 Multimodal Reflection. Across all modalities, participants exhibited affective awareness and emotional regulation through reflection. Writing proved the most effective for processing emotions, offering a clear, intuitive way to express thoughts. However, through the visual art and body movement modalities, participants reported a sense of observing the experience from a bird's-eye view, which helped them confront it.

Our study highlights the benefits of repeated reflections. Reflecting on the positive and negative experiences through each of the different modalities helped participants glean new perspectives and gain emotional control [12] as a result of the repeated reflections. While we counterbalanced the modality order, qualitative ordering effects were observed, such as writing before movement seemed to ease the process and participants gained a sense of mastery through repetition, regardless of prior familiarity with the modality [4]. Moreover, rumination over past negative experiences or indulgence in nostalgia without confronting the past are both extremes of emotional valence, which can be balanced by performing both reflection conditions in moderation [29]. Thus, multimodal self-reflection tools that support both positive and negative reflection through multiple modalities can offer a balanced and holistic approach [24].

5.2.2 Familiarity and Signifiers. Familiarity or prior experiences with each modality influenced participants’ comfort and engagement. For example, graduate students in our study who were accustomed to writing found it to be a more intuitive medium. Conversely, participants unfamiliar with the movement modality faced initial discomfort but indicated that introducing familiarity through guided practice could be beneficial. Participants suggested adding props or music to enhance intuition and engagement. Such elements help users connect emotionally and feel comfortable with new modalities [46]. Scaffolding the experience or demonstration videos can further support engagement [69]. In the visual modality, participants relied on the cutouts, colors, and shapes provided as starting points or triggers for creativity or emotions provoked from memory recall [5]. This aligns with UX design principles of providing signifiers that promote ease of use and encourage desired actions [41].

Cultural background may have also influenced ease with modalities, as participants from dance-emphasizing cultures felt less awkward with movement [33, 73]. Cultural stigmas around mental health could have impacted sharing: one participant submitted a blank artifact, hesitant to disclose personal details [1]. While this represents a limitation of the study, it also highlights the need for culturally sensitive designs that respect privacy. Personalized interfaces and transparent data policies can build trust and encourage authentic self-expression [27].

5.3 Limitations and Future Work

Our sample of participants was somewhat small and lacked racial and ethnic diversity which may increase the risk of Type II errors in the quantitative analysis [58]. While this limitation may affect the generalizability of the quantitative results, our primary focus was on qualitative analysis, which prioritizes transferability [50]. Moreover, the sample size aligns with the median reported in qualitative research in HCI [9] and the racial and ethnic diversity is representative of the graduate student population at our institution. Our quantitative results primarily support and contextualize the qualitative findings and may apply to institutions with similar demographics. However, to understand the implications of multimodal reflection tools for graduate students more broadly, future research should recruit a larger, more diverse sample to capture a wider range of experiences. Studies should also address graduate students’ specific challenges to explore how self-expression modalities support academic and personal growth.

As the goal of the study was to inform the design of future digital self-reflection tools, we did not develop a user interface [7]. Building on current results, our future work will develop and evaluate a digital self-reflection prototype that supports the specific needs of graduate students in managing their emotional well-being. Co-design sessions with a diverse group of graduate students will be conducted. Additionally, including physiological measures like heart rate variability and skin conductance with self-reports can provide objective emotional insights.

6 Conclusion

This study explored how writing, visual art, and movement impact self-reflection and emotional well-being in graduate students. Positive reflection evoked excitement; negative reflection brought relief. Writing fostered introspection, visual art sparked creativity, and movement enabled embodied emotional processing. Participants felt most creative with writing and visual art. Each modality played a complementary role in self-expression. A flexible, multimodal approach can enhance reflection, creativity, and stress management [21]. Future work should integrate intelligent, affective, and multimodal technologies to support graduate student well-being.

7 Safe and Responsible Innovation Statement

All data were collected with informed consent under IRB approval, and care was taken to avoid emotional harm by including an optional positive reflection at the study's end. The work promotes inclusive mental health technologies by offering diverse non-verbal options for self-expression, acknowledging cultural variation in comfort and access. While no digital system was developed, the findings guide future multimodal tools that respect privacy, encourage emotional autonomy, and support well-being without reinforcing rumination or emotional bias.

References

- Ahmed A. Ahad, Marcos Sanchez-Gonzalez, and Patricia Junquera. 2023. Understanding and Addressing Mental Health Stigma Across Cultures for Improving Psychiatric Care: A Narrative Review. Cureus 15, 5 (May 2023), e39549. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39549

- Surely Akiri, Vasundhara Joshi, Sanaz Taherzadeh, Gary Williams, Helena M Mentis, and Andrea Kleinsmith. 2024. Design and Preliminary Evaluation of a Stress Reflection System for High-Stress Training Environments. In Companion Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction. 11–15.

- Juanita Argudo. 2021. Expressive writing to relieve academic stress at university level. Profile Issues in TeachersProfessional Development 23, 2 (2021), 17–33.

- James Arnéra, Chun Hei Michael Chan, and Mauro Cherubini. 2024. Digital, Analog, or Hybrid: Comparing Strategies to Support Self-Reflection. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. 3435–3452.

- Agnese Augello, Ignazio Infantino, Giovanni Pilato, Riccardo Rizzo, and Filippo Vella. 2013. Binding representational spaces of colors and emotions for creativity. Biologically Inspired Cognitive Architectures 5 (July 2013), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bica.2013.05.005

- Eric PS Baumer. 2015. Reflective informatics: conceptual dimensions for designing technologies of reflection. In Proceedings of the 33rd annual ACM conference on human factors in computing systems. 585–594.

- Mela Bettega, Raul Masu, Nicolai Brodersen Hansen, and Maurizio Teli. 2022. Off-the-shelf digital tools as a resource to nurture the commons. In Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2022 - Volume 1(PDC ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1145/3536169.3537787

- Stephen Burgess, Simon G Thompson, and Crp Chd Genetics Collaboration. 2011. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. International journal of epidemiology 40, 3 (2011), 755–764.

- Kelly Caine. 2016. Local standards for sample size at CHI. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 981–992.

- Ryan Francis O Cayubit. 2017. Effect of expressive writing on the subjective well-being of university students. Studies in Asia 25, 1 (2017), 60–68.

- Félix Cova, Felipe Garcia, Cristian Oyanadel, Loreto Villagran, Dario Páez, and Carolina Inostroza. 2019. Adaptive Reflection on Negative Emotional Experiences: Convergences and Divergence Between the Processing-Mode Theory and the Theory of Self-Distancing Reflection. Frontiers in Psychology 10 (Sept. 2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01943 Publisher: Frontiers.

- Patrick J. Curran and Daniel J. Bauer. 2011. The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology 62 (2011), 583–619. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356

- Claudia Daudén Roquet, Nikki Theofanopoulou, Jaimie L Freeman, Jessica Schleider, James J Gross, Katie Davis, Ellen Townsend, and Petr Slovak. 2022. Exploring situated & embodied support for youth's mental health: design opportunities for interactive tangible device. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 1–16.

- Kristen A. Diliberto-Macaluso and Briana Lyn Stubblefield. 2015. The use of painting for short-term mood and arousal improvement. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 9, 3 (2015), 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039237 Place: US Publisher: Educational Publishing Foundation.

- Amanda Díaz-García, Alberto González-Robles, Sonia Mor, Adriana Mira, Soledad Quero, Azucena García-Palacios, Rosa María Baños, and Cristina Botella. 2020. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): psychometric properties of the online Spanish version in a clinical sample with emotional disorders. BMC Psychiatry 20, 1 (Feb. 2020), 56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2472-1

- Elizabeth Victoria Eikey, Clara Marques Caldeira, Mayara Costa Figueiredo, Yunan Chen, Jessica L. Borelli, Melissa Mazmanian, and Kai Zheng. 2021. Beyond self-reflection: introducing the concept of rumination in personal informatics. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 25, 3 (June 2021), 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-021-01573-w

- Teresa M Evans, Lindsay Bira, Jazmin Beltran Gastelum, L Todd Weiss, and Nathan L Vanderford. 2018. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature biotechnology 36, 3 (2018), 282–284.

- Elena Faccio, Francesca Turco, and Antonio Iudici. 2019. Self-writing as a tool for change: the effectiveness of a psychotherapy using diary. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome 22, 2 (July 2019). https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2019.378 Number: 2.

- Samira Feizi, Bärbel Knäuper, and Frank Elgar. 2024. Perceived stress and well-being in doctoral students: Effects on program satisfaction and intention to quit. Higher Education Research & Development 43, 6 (2024), 1259–1276.

- Connor L Ferguson and Julie A Lockman. 2024. Increasing PhD student self-awareness and self-confidence through strengths-based professional development. In Frontiers in Education, Vol. 9. Frontiers Media SA, 1379859.

- Andreas Foltyn and Jessica Deuschel. 2021. Towards reliable multimodal stress detection under distribution shift. In Companion Publication of the 2021 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction. 329–333.

- Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2001. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist 56, 3 (2001), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218 Place: US Publisher: American Psychological Association.

- Emily Frith and Stephanie E. Miller. 2024. Creativity in motion: examining the impact of meaningful movement on creative cognition. Frontiers in Cognition 3 (Aug. 2024). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcogn.2024.1386375 Publisher: Frontiers.

- Debasmita Ghose, Oz Gitelson, and Brian Scassellati. 2024. Integrating Multimodal Affective Signals for Stress Detection from Audio-Visual Data. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction. 22–32.

- Michaela Gläser-Zikuda. 2012. Self-Reflecting Methods of Learning Research. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, Norbert M. Seel (Ed.). Springer US, Boston, MA, 3011–3015. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_821

- Rebecca K Grady, Rachel La Touche, Jamie Oslawski-Lopez, Alyssa Powers, and Kristina Simacek. 2014. Betwixt and between: The social position and stress experiences of graduate students. Teaching Sociology 42, 1 (2014), 5–16.

- Anatoliy Gruzd and Ángel Hernández-García. 2018. Privacy Concerns and Self-Disclosure in Private and Public Uses of Social Media. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 21, 7 (July 2018), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0709

- Shawn Joseph Harrington, Orrin-Porter Morrison, and Antonio Pascual-Leone. 2018. Emotional processing in an expressive writing task on trauma. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 32 (Aug. 2018), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.06.001

- Victoria Hollis, Artie Konrad, Aaron Springer, Matthew Antoun, Christopher Antoun, Rob Martin, and Steve Whittaker. 2017. What does all this data mean for my future mood? Actionable analytics and targeted reflection for emotional well-being. Human–Computer Interaction 32, 5-6 (2017), 208–267.

- Zartashia Kynat Javaid and Khalid Mahmood. 2023. Efficacy of expressive writing therapy in reducing embitterment among university students. Pakistan JL Analysis & Wisdom 2 (2023), 136.

- Tyler Kay, Meghna Raswan, Hector M Camarillo-Abad, Trudi Di Qi, and Franceli L Cibrian. 2023. Using Virtual Reality to Foster Creativity for Co-design a New Self-Expression and Relaxation Virtual Environment for Students. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Creativity and Cognition. 365–367.

- Eileen Kennedy-Moore and Jeanne C. Watson. 2001. How and when does emotional expression help?Review of General Psychology 5, 3 (2001), 187–212. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.3.187 Place: US Publisher: Educational Publishing Foundation.

- Heejung S. Kim and Deborah Ko. 2007. Culture and self-expression. In The self. Psychology Press, New York, NY, US, 325–342.

- Mustafa Koç, Tuğba Seda Çolak, Betül Düşünceli, and Samet Makas. 2019. Investigation of Emotional Expression as a Predictor of Psychological Symptoms. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies 6, 3 (Sept. 2019), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.17220/ijpes.2019.03.002 Number: 3.

- Gerry Leisman, Ahmed A. Moustafa, and Tal Shafir. 2016. Thinking, Walking, Talking: Integratory Motor and Cognitive Brain Function. Frontiers in Public Health 4 (May 2016). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00094 Publisher: Frontiers.

- Johanna Leseho and Lisa Rene Maxwell. 2010. Coming alive: creative movement as a personal coping strategy on the path to healing and growth. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 38, 1 (Feb. 2010), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880903411301 Publisher: Routledge _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880903411301.

- Angela K-y Leung, Letty Kwan, Shyhnan Liou, Chi-yue Chiu, Lin Qiu, and Jose C Yong. 2013. The role of instrumental emotion regulation in the emotions-creativity link: How worries render neurotic individuals more creative. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM Conference on Creativity & Cognition. 332–336.

- Katia Levecque, Frederik Anseel, Alain De Beuckelaer, Johan Van der Heyden, and Lydia Gisle. 2017. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research policy 46, 4 (2017), 868–879.

- Bin Li, Qin Zhu, Aimei Li, and Rubo Cui. 2023. Can Good Memories of the Past Instill Happiness? Nostalgia Improves Subjective Well-Being by Increasing Gratitude. Journal of Happiness Studies 24, 2 (Feb. 2023), 699–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00616-0

- Elizabeth A. Linnenbrink. 2006. Emotion Research in Education: Theoretical and Methodological Perspectives on the Integration of Affect, Motivation, and Cognition. Educational Psychology Review 18, 4 (Dec. 2006), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9028-x

- Eva Mackamul, Géry Casiez, and Sylvain Malacria. 2023. Exploring visual signifier characteristics to improve the perception of affordances of in-place touch inputs. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 7, MHCI (2023), 1–32.

- Sylvia Anne Mackie and Glen William Bates. 2019. Contribution of the doctoral education environment to PhD candidates’ mental health problems: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development 38, 3 (2019), 565–578.

- Marta Maslej, Alan R. Rheaume, Louis A. Schmidt, and Paul W. Andrews. 2020. Using Expressive Writing to Test an Evolutionary Hypothesis About Depressive Rumination: Sadness Coincides with Causal Analysis of a Personal Problem, Not Problem-solving Analysis. Evolutionary Psychological Science 6, 2 (June 2020), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00219-8

- Mercè Mateu, Silvia Garcías, Luciana Spadafora, Ana Andrés, and Eulàlia Febrer. 2021. Student moods before and after body expression and dance assessments. Gender perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 11 (2021), 612811.

- Sarah McNicol, Cathy Lewin, Anna Keune, and Tarmo Toikkanen. 2014. Facilitating student reflection through digital technologies in the iTEC project: pedagogically-led change in the classroom. In International conference on learning and collaboration technologies. Springer, 297–308.

- Amy Melniczuk, Meng Liang, and Julian Preissing. 2025. Exploring Tangible Designs to Improve Interpersonal Connectedness in Remote Group Brainstorming. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. 1–14.

- Ine Mols, Elise van den Hoven, and Berry Eggen. 2020. Everyday Life Reflection: Exploring Media Interaction with Balance, Cogito & Dott. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction(TEI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1145/3374920.3374928

- Mahin Naderifar, Hamideh Goli, and Fereshteh Ghaljaie. 2017. Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in development of medical education 14, 3 (2017).

- Natalie Perkins and Arlene Schmid. 2019. Increasing Emotional Intelligence through Self-Reflection Journals: Implications for Occupational Therapy Students as Emerging Clinicians. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education (JOTE) 3, 3 (Jan. 2019). https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2019.030305

- Denise F Polit and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2010. Generalization in quantitative and qualitative research: Myths and strategies. International journal of nursing studies 47, 11 (2010), 1451–1458.

- Mimmu Rankanen, Marianne Leinikka, Camilla Groth, Pirita Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, Maarit Mäkelä, and Minna Huotilainen. 2022. Physiological measurements and emotional experiences of drawing and clay forming. The Arts in Psychotherapy 79 (2022), 101899.

- Fujiko Robledo Yamamoto, Janghee Cho, Amy Voida, and Stephen Voida. 2023. “We are Researchers, but we are also Humans”: Creating a Design Space for Managing Graduate Student Stress. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 30, 5 (Sept. 2023), 75:1–75:33. https://doi.org/10.1145/3589956

- Liana Santos Alves Peixoto, Sonia Maria Guedes Gondim, and Cícero Roberto Pereira. 2022. Emotion Regulation, Stress, and Well-Being in Academic Education: Analyzing the Effect of Mindfulness-Based Intervention. Trends in Psychology 30, 1 (2022), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00092-0

- Donald A Schön. 2017. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge.

- Daniel L. Segal, Heather C. Tucker, and Frederick L. Coolidge. 2009. A Comparison of Positive Versus Negative Emotional Expression in a Written Disclosure Study Among Distressed Students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 18, 4 (May 2009), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770902901345 Publisher: Routledge _eprint: https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770902901345.

- Tal Shafir, Stephan F. Taylor, Anthony P. Atkinson, Scott A. Langenecker, and Jon-Kar Zubieta. 2013. Emotion regulation through execution, observation, and imagery of emotional movements. Brain and Cognition 82, 2 (July 2013), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2013.03.001

- Tal Shafir, Rachelle P. Tsachor, and Kathleen B. Welch. 2016. Emotion Regulation through Movement: Unique Sets of Movement Characteristics are Associated with and Enhance Basic Emotions. Frontiers in Psychology 6 (Jan. 2016). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02030 Publisher: Frontiers.

- Jacob Shreffler and Martin R Huecker. 2020. Type I and type II errors and statistical power. (2020).

- Apoorva Shukla, Sonali G. Choudhari, Abhay M. Gaidhane, and Zahiruddin Quazi Syed. 2022. Role of Art Therapy in the Promotion of Mental Health: A Critical Review. Cureus 14, 8 (Aug. 2022), e28026. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.28026

- Jaime Snyder, Mark Matthews, Jacqueline Chien, Pamara F Chang, Emily Sun, Saeed Abdullah, and Geri Gay. 2015. Moodlight: Exploring personal and social implications of ambient display of biosensor data. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work & social computing. 143–153.

- Anna Ståhl, Kristina Hook, Martin Svensson, Alex S Taylor, and Marco Combetto. 2009. Experiencing the affective diary. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 13 (2009), 365–378.

- Anna Sutton. 2016. Measuring the effects of self-awareness: Construction of the self-awareness outcomes questionnaire. Europe's journal of psychology 12, 4 (2016), 645.

- Cher-Yi Tan, Chun-Qian Chuah, Shwu-Ting Lee, and Chee-Seng Tan. 2021. Being Creative Makes You Happier: The Positive Effect of Creativity on Subjective Well-Being. IJERPH 18, 14 (2021), 1–14. https://ideas.repec.org//a/gam/jijerp/v18y2021i14p7244-d589553.html Publisher: MDPI.

- Elizabeth J. Tisdell. 2025. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation (fifth edition ed.). Jossey-Bass, Hoboken, New Jersey.

- Allison S Troy, Amanda J Shallcross, Anna Brunner, Rachel Friedman, and Markera C Jones. 2018. Cognitive reappraisal and acceptance: Effects on emotion, physiology, and perceived cognitive costs.Emotion 18, 1 (2018), 58.

- Susann Ullrich, Yfke C de Vries, Simone Kühn, Dimitris Repantis, Martin Dresler, and Kathrin Ohla. 2015. Feeling smart: Effects of caffeine and glucose on cognition, mood and self-judgment. Physiology & behavior 151 (2015), 629–637.

- Nadine Wagener, Daniel Christian Albensoeder, Leon Reicherts, Paweł W Woźniak, Yvonne Rogers, and Jasmin Niess. 2025. TogetherReflect: Supporting Emotional Expression in Couples Through a Collaborative Virtual Reality Experience. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–16.

- Nadine Wagener, Arne Kiesewetter, Leon Reicherts, Paweł W Woźniak, Johannes Schöning, Yvonne Rogers, and Jasmin Niess. 2024. MoodShaper: A Virtual Reality Experience to Support Managing Negative Emotions. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. 2286–2304.

- Nadine Wagener, Leon Reicherts, Nima Zargham, Natalia Bartłomiejczyk, Ava Elizabeth Scott, Katherine Wang, Marit Bentvelzen, Evropi Stefanidi, Thomas Mildner, Yvonne Rogers, and Jasmin Niess. 2023. SelVReflect: A Guided VR Experience Fostering Reflection on Personal Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems(CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580763

- Liz Weiland. 2012. Focusing-oriented Art Therapy as a Means of Stress Reducation with Graduate Students. Ph. D. Dissertation. Notre Dame de Namur University, Belmont, Calif.

- Xiaofei Wu, Tingting Guo, Tengteng Tan, Wencai Zhang, Shaozheng Qin, Jin Fan, and Jing Luo. 2019. Superior emotional regulating effects of creative cognitive reappraisal. NeuroImage 200 (Oct. 2019), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.061

- Bin Yu, Jun Hu, Mathias Funk, and Loe Feijs. 2018. DeLight: biofeedback through ambient light for stress intervention and relaxation assistance. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 22 (2018), 787–805.

- Di Zhou. 2022. The Elements of Cultural Power: Novelty, Emotion, Status, and Cultural Capital. American Sociological Review 87, 5 (Oct. 2022), 750–781. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221123030 Publisher: SAGE Publications Inc.

- David Zhou and Sarah Sterman. 2024. Ai. llude: Investigating Rewriting AI-Generated Text to Support Creative Expression. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference on Creativity & Cognition. 241–254.

A Study Materials

A.1 Semi-Structured Interview Prompts

The following questions were posed to each participant in the exit interview:

- What was your overall experience of our session today?

- Describe the emotions you experienced during each modality: Writing, Art, Movement.

- Which modality (writing, art, movement) did you prefer for the self-reflection? Please rank the modalities in order of preference and explain your reasoning.

- Do you have the habit of expressing your reflection on experience through any of the self-expression techniques performed today?

- After this session, do you find any benefit in self-reflection of your positive/negative experiences?

- If you were to continue self-reflection of experiences in the future, which modality would you choose?

Footnote

⁎Both authors contributed equally to this research.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

ICMI '25, Canberra, ACT, Australia

© 2025 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-1499-3/25/10.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3716553.3750798