Building Collaborative Art Creation Environment for People with Intellectual Disabilities through Adaptive Fabric Art Workshops

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3688497

ASSETS '24: The 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, St. John's, NL, Canada, October 2024

This study focuses on designing and implementing adaptive fabric art workshops within a collaborative art creation environment tailored for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Conducted in an inclusive gallery setting, these workshops aimed to enhance self-expression for individuals with intellectual disabilities through simplified art-making processes and user-friendly materials and tools. Following these workshops, the created artworks were exhibited at the gallery. Based on reflections with stakeholders, we suggest the development of online sharing platforms that could facilitate ongoing learning and collaboration for supporters, ultimately promoting inclusivity and accessibility in community art activities for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

ACM Reference Format:

Qianrong Fu, Giulia Barbareschi, and Chihiro Sato. 2024. Building Collaborative Art Creation Environment for People with Intellectual Disabilities through Adaptive Fabric Art Workshops. In The 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS '24), October 27--30, 2024, St. John's, NL, Canada. ACM, New York, NY, USA 4 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3688497

1 Introduction

People with intellectual disabilities (ID) often face significant challenges that hinder their engagement in local communities, including physical and communicative barriers, limited access to social activities, and social isolation [10]. Most creative and cultural activities which are organised at the community level are not customized to meet the diverse needs of this population [14]. Addressing these limitations is crucial for enhancing their social contact, reducing experiences of social isolation, and reducing disability stigma in the community due to infrequent social interactions between people with and without disabilities [3, 17]. Overcoming these barriers through meaningful engagement is also key for improving the mental well-being of individuals with ID [8].

Handcrafting and art-making are recognized as meaningful and therapeutic methods, particularly beneficial for individuals who face challenges with verbal self-expression [15]. Adaptive art is a specialized field of art therapy that focuses on modifying traditional art-making processes, tools, and materials to accommodate the diverse needs of individuals with disabilities, aiming to make art accessible and inclusive [14], however such activities are rarely available at the community level due to a lack of awareness, resources, and trained facilitators [1]. This paper tackles the research question “How can adaptive art workshops be structured to create a collaborative art creation environment for participants with ID at the community level?”. The research team designed and conducted two workshops for people with profound ID between 2023 and 2024 in an accessible art gallery in Japan, where the finished artworks were also exhibited at.

Based on the insights gained from conducting the workshops with individuals with ID and the feedback we received from stakeholders, we suggest the development of online sharing platforms for adaptive art workshops aiming to facilitate ongoing learning, collaboration, and innovation among art facilitators from different locations, which would foster inclusivity and accessibility in art therapy for people with ID.

2 Related Work

2.1 Adaptive Art

Loesl emphasizes the user-centric approach of adaptive art, which requires interdisciplinary efforts and integration among various stakeholders [14]. This approach not only facilitates the creation of art but also promotes inclusivity and expands the field of accessible arts, however, further development in assistive technologies is needed to better cater to the diverse needs of people with disabilities. Recognizing the limitations imposed by traditional art-making methods, simplifying the process of art creation is necessary to make it easier and barrier-free for diverse needs and abilities [18]. Fabric, a material familiar in daily life, helps individuals with ID become more involved in the art-making process [9]. Making fabric collages is a popular and accessible medium for educational, therapeutic, and recreational settings [6].

2.2 Creating Art Experiences and Environments for People with ID

Previous research have discussed artistic technologies and environments for people with physical as well as intellectual disabilities [2, 4]. Previous studies illustrated how creating a “supportive” environment provides participants with the necessary assistance and resources to help them succeed, involving ensuring physical accessibility with adaptive equipment and accessible facilities, and offering professional, well-structured guidance from trained instructors [11, 12], yet a purely supportive environment may neglect the potential of individuals with ID [13]. Instead, a "collaborative" environment can involve cooperative efforts among various stakeholders working together towards a common goal with shared expertise, mutual respect, coordinated actions, and joint planning [13, 16], however, such an approach is rarely implemented when people with intellectual disabilities are involved in art experiences.

According to Kosma [11] and Coleman [5], there are six key points to create adaptive art experience for people with ID and motivate them to participate in art creation; (1) understand users’ needs, (2) address barriers, (3) set proper goals and “rewards” [7], (4) engage for enjoyment, (5) ensure supportive environment (6) encourage positive reinforcement. This study leverages these six key points collaborative art creation environment.

3 Adaptive Fabric Art Workshops

3.1 Settings and Positionality

The research team conducted two adaptive fabric art workshops each involving 6 individuals with profound ID from a local center supporting people with disabilities in Yachiyo-city, Chiba, Japan, and were carried out at an accessible community art gallery in the same city between 2023 and 2024. The center serves around 40 individuals with diverse needs, aiming to enhance their quality of life through creative and productive activities such as street cleaning, gardening, and art and music events. Despite participants’ interest in art-related events, supporters lack specialized training in art activities, which led the center to seek opportunities to collaborate with our research team to organise and deliver the workshops. The center's management team helped to identify the participants for the workshops.

Since 2019, our research team has collaborated with various entities within Yachiyo-city, centering around the social welfare office, to which the center is associated. The research team is composed of diverse international members between 20 and 50 years of age with different expertise including art therapy, HCI, accessibility, service design, and community-based design. Many of the members have been running a wide variety of projects and activities together with the support and participation of local residents—which have led to a strong relationship of trust—and the relationship with the local gallery and the local disability supporting center was facilitated through referrals. This study was initially motivated by an informal conversation between the local gallery and the research team, in which the discussion was about how to make the city gallery more inclusive and inviting for diverse citizens.

3.2 Methodology

3.2.1 Surveys to understand participants’ needs. Before constructing the adaptive art workshops, the research team sent a pre-workshop survey to the local disability centers’ life supporters to understand the users’ needs and preferences and identify the level of support required. The survey included questions about the types of activities they enjoyed, their preferred methods of communication, and any challenges they have faced during creative tasks.

The results revealed several key points about the users; in particularly highlighting their diverse interests and different ways to communicate both verbally and non, according to individual abilities. Some participants could converse with spoken language (though supporters needed to be mindful of difficulties with nuanced expressions), some could articulate single words often combined with gestures, and some non-verbal individuals relied on gestures, sounds, and physically guiding their supporters. It also pointed out their limitations of hand control, with only a few who had experience using cutting tools like scissors. These findings were crucial for the research team, as they highlighted the need for clear simple language, creating visual aids using photographs, and providing user-friendly tools and pre-cut materials to accommodate varying ability levels.

3.2.2 Conversations to decide the workshop goals. To set proper goals for the workshop, the research team discussed with the managers of the local disability support center, which events could be accessible but also suitable for the production of valuable outputs. It was collectively agreed that the maximum length of the workshop would be one hour; the participants with ID could comfortably engage for the length, and the workshop would not significantly alter their daily schedules.

Additionally, consultations with occupational therapists and professional artists working with people with ID helped establish the details—the size of the artwork, the type of materials to use, and the appropriate utensils—which would allow participants to unleash their creativity without feeling overwhelmed and enjoy the creation process but also manage everything within the hour. It was emphasized that each participant shall be expected to finish at least one piece of artwork during the session, ensuring they are satisfied with their artwork by the end of the session.

3.2.3 Selecting workshop themes to ensure enjoyment. Of the two workshops conducted, the first one was scheduled around Christmas, which is a festive season of enjoyment for most people in Japan regardless of their religion. We therefore decided on creating Christmas tree ornaments; but as fabric collage decorations on cardboard. The second workshop focused on themes closer to the participants’ daily lives in the center, such as gardening and food. The materials chosen for this workshop were gloves, which provide a sense of familiarity in everyday activities.

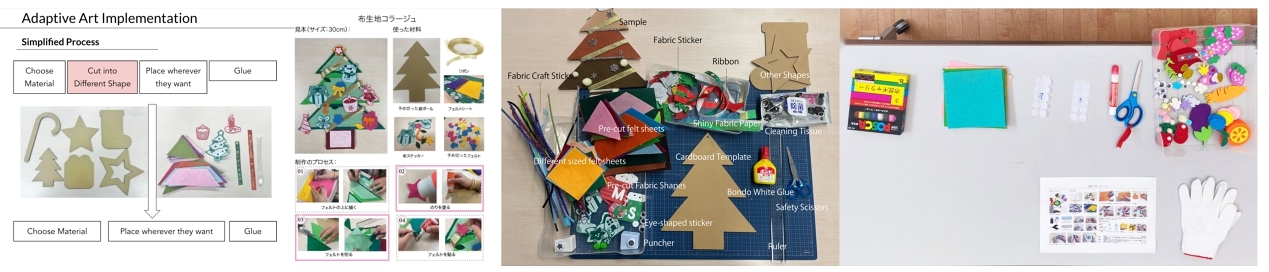

3.2.4 Implementing Adaptive Art to Scaffold Participation for People with ID. Traditional collage-making usually takes four steps: (1) choosing materials, (2) cutting the materials into different shapes, (3) placing the materials at the designated position, and (4) gluing the materials together as seen in Figure 2. The research team created the following three elements to ensure the handcrafting process was straightforward and foster smooth facilitation.

Facilitation Sheet. Since most of the participants had limitations in verbal abilities and hand usage, life supporters and research team facilitators needed to assist with actions such as cutting and pasting during the workshop. A guiding facilitation sheet (Figure 2) was created with detailed processes along with the materials and tools to be used in the workshop to outline these tasks clearly.

Material and Tool Selection. The collage base materials—the cardboard and the gloves—served as adaptable and user-friendly foundations for the fabric collages. These materials were easily accessible, affordable, and could provide sturdy support for various decorative elements. The adhesives selected for the workshops were and quick-drying and easy to manage, ensuring a smooth and efficient art-making process.

Individual Material Kits. The research team prepared fabric sheets for participants to draw, cut, glue, and customize into their preferred shapes. Additionally, pre-cut felt sheets, fabric stickers, craft pipe cleaners, fabric balls, eye stickers, ribbons, and fiber paper were provided in individual boxes for each participant, ensuring they had the freedom to create artwork without concern about material limitations.

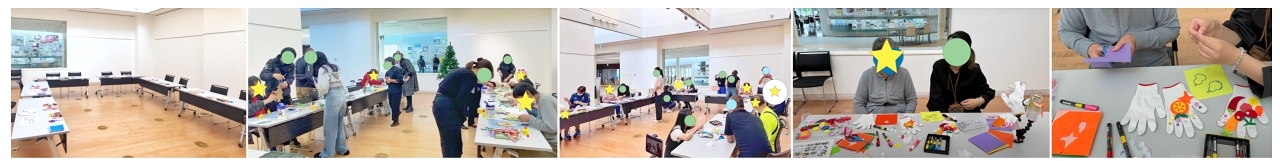

3.2.5 Setting up a collaborative art creation environment. Both workshops were held in a local art gallery in the same city physically accessible to individuals using wheelchairs, in one of their exhibition rooms. Tables were laid out in a u-shaped format to promote a collaborative atmosphere (See Figure 3). Each participant was provided with a designated workspace that included a table and chairs arranged to facilitate interaction with their life supporters and the research team.

4 Participants’ Behavior during Workshops and its Outcomes

Many participants quickly engaged with the provided materials, expressing excitement and satisfaction with their creations. Some showed significant initiative in exploring different techniques and materials; cutting the fabric, experimenting with new methods for gluing, and exploring pre-cut shapes and stickers. This active participation was assisted by the life supporters and research team, across various tasks such as cutting shapes, making ribbons, and gluing materials. Within the limited time, the six participants all together created 12 tree ornaments for the first workshop and 18 glove artworks for the second workshop (See Figure 1). Each participant in both workshops created at least one artwork, with some participants making up to four pieces. These completed artworks were exhibited at the gallery to showcase to the broader community.

Based on the post-survey conducted on the disability centers’ life supporters and the researcher team's collective observation during the workshop, the collaborative process and support from facilitators significantly contributed to a collective positive experience. Participants were highly satisfied with their artwork and enjoyed the workshops. The feedback from the supporting center highlighted the success and adaptability of the handcraft fabric collage workshop for participants with ID. Most life supporters noted initial challenges with cutting tools but overall effective engagement, which proved the adaptive tools and materials helped participants overcome barriers of art creation.

5 Discussion

As mentioned in Section 3.2, the research team encountered difficulties in defining goals and addressing barriers for individuals with ID during the workshop planning process. Gaining insights required considerable effort, including consultations with experts and occupational therapists situated in different locations and affiliated with different institutions. These challenges highlighted the need for a more accessible way to gather references and insights. To address this, we propose the development of an online platform for life supporters and art educators to conduct adaptive art workshops. This platform would facilitate the sharing of ideas, discussions, and consultations, making it easier for educators to access resources and collaborate. The platform is particularly valuable for those who wish to conduct similar art workshops but may be uncertain about the procedures, themes, materials, or processes involved. By providing detailed guidelines, best practices, and examples from successful workshops, the platform can help educators confidently plan and execute adaptive art workshops tailored to the needs of their participants.

This platform should encompass several key elements to support the various stakeholders. Firstly, a community forum would facilitate discussions, idea-sharing, and consultations among educators. Secondly, video tutorials and workshop recordings would provide practical guidance and learning opportunities. Thirdly, a comprehensive database featuring various adaptive art themes, facilitation sheets, and materials and tool suggestions would serve as a valuable resource. By enabling educators to share best practices, access valuable resources, and receive guidance on conducting adaptive art workshops, this platform aims to support educators in enhancing their practices and ultimately improving the artistic experiences and outcomes for individuals with disabilities.

6 Conclusion

The adaptive fabric art workshops for individuals with ID effectively enhanced self-expression using user-friendly tools and engaging themes, simplifying the art-making process for various ability levels. Positive participant behaviors and feedback from life supporters confirmed the effectiveness of the collaborative art creation environment. Meanwhile, the research team faced challenges in defining goals and addressing barriers, highlighting the need for efficient expertise gathering. Therefore, developing online platforms enabling inclusive art educators to share best practices and access valuable resources could be beneficial to ultimately enhance the quality and reach of adaptive art education for individuals with disabilities and promote inclusivity in society.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research(B) JP23H03441. We gratefully acknowledge the Yachiyo City Gallery, Koike Supporting Center, and local artist Ms.Mari and Ms.Komachida for their essential contributions. Special thanks to the participants, as well as the faculty and members of Keio Media Design who facilitated the workshops.

References

- Angela Novak Amado. 2014. Building relationships between adults with intellectual disabilities and community members: Strategies, art, and policy. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 1, 2 (2014), 111–122.

- Giulia Barbareschi and Masa Inakage. 2022. Assistive or Artistic Technologies? Exploring the Connections between Art, Disability and Wheelchair Use. In Proceedings of the 24th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (Athens, Greece) (ASSETS ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 11, 14 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3517428.3544799

- Tyler Bruefach and John R Reynolds. 2022. Social isolation and achievement of students with learning disabilities. Social Science Research 104 (2022), 102667.

- Sifan Chen, Giulia Barbareschi, and Chihiro Sato. 2024. Empathy-Building Through Personalized Pixel Crafting: A Co-Creation Platform for Researchers and Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. In Proceedings of the 3rd Empathy-Centric Design Workshop: Scrutinizing Empathy Beyond the Individual (Honolulu, HI, USA) (EmpathiCH ’24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3661790.3661796

- Mari Beth Coleman and Elizabeth Stephanie Cramer. 2015. Creating meaningful art experiences with assistive technology for students with physical, visual, severe, and multiple disabilities. Art Education 68, 2 (2015), 6–13.

- Ann Futterman Collier. 2011. The Well-Being of Women Who Create With Textiles: Implications for Art Therapy. Art Therapy 28, 3 (2011), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2011.597025

- Aurora Constantin, Hilary Johnson, Elizabeth Smith, Denise Lengyel, and Mark Brosnan. 2017. Designing computer-based rewards with and for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and/or Intellectual Disability. Computers in Human Behavior 75 (2017), 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.030

- Eric Emerson, Nicola Fortune, Gwynnyth Llewellyn, and Roger Stancliffe. 2021. Loneliness, social support, social isolation and wellbeing among working age adults with and without disability: Cross-sectional study. Disability and health journal 14, 1 (2021), 100965.

- Eliza S. Homer. 2015. Piece Work: Fabric Collage as a Neurodevelopmental Approach to Trauma Treatment. Art Therapy 32, 1 (2015), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.992824

- Craig H Kennedy, Robert H Horner, and J Stephen Newton. 1989. Social contacts of adults with severe disabilities living in the community: A descriptive analysis of relationship patterns. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps 14, 3 (1989), 190–196.

- Maria Kosma, Bradley J. Cardinal, and Pauli Rintala. 2002. Motivating Individuals With Disabilities to Be Physically Active. Quest 54, 2 (2002), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2002.10491770

- Gloria L Krahn, Laura Hammond, and Anne Turner. 2006. A cascade of disparities: health and health care access for people with intellectual disabilities. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews 12, 1 (2006), 70–82.

- Suvi Lakkala, Alvyra Galkienė, Julita Navaitienė, Tamara Cierpiałowska, Susanne Tomecek, and Satu Uusiautti. 2021. Teachers Supporting Students in Collaborative Ways—An Analysis of Collaborative Work Creating Supportive Learning Environments for Every Student in a School: Cases from Austria, Finland, Lithuania, and Poland. Sustainability 13, 5 (2021), 2804. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052804

- Susan D Loesl. 2012. The adaptive art specialist: An integral part of a student's access to art. The intersection of arts education and special education: Exemplary programs and approaches (2012), 47.

- Cathy A Malchiodi. 2011. Handbook of art therapy. Guilford Press.

- Oussama Metatla, Anja Thieme, Emeline Brulé, Cynthia Bennett, Marcos Serrano, and Christophe Jouffrais. 2018. Toward classroom experiences inclusive of students with disabilities. Interactions 26, 1 (2018), 40–45.

- Hannah A Pelleboer-Gunnink, Wietske van Oorsouw, Jaap van Weeghel, and Petri Embregts. 2021. Familiarity with people with intellectual disabilities, stigma, and the mediating role of emotions among the Dutch general public.Stigma and Health 6, 2 (2021), 173.

- Jennifer M Platt and Donna Janeczko. 1991. Adapting art instruction for students with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children 24, 1 (1991), 10–12.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. For all other uses, contact the owner/author(s).

ASSETS '24, October 27–30, 2024, St. John's, NL, Canada

© 2024 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-0677-6/24/10.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3688497