Working at the speed of trust Respect relevance and reciprocity encouraging participation with remote First Nations communities in Australia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3704611.3704615

Asian CHI 2024: Asian CHI Symposium 2024, Online, Malaysia, September 2024

Globally, First Nations languages are under threat. For millennia, First Nations languages have been passed on intergenerationally through oral transmission and traditional ways of learning. Schools and communities look toward technology as a tool for stemming the loss and maintaining, preserving and revitalising languages and engaging students in their learning. Two iPad projects in very remote Aboriginal communities have demonstrated how iPad activities can be co-designed with Aboriginal educators to create culturally appropriate resources and activities to support learning in traditional languages. Professional learning is key and must be contextualised and adapted to suit the remote context, working closely and respectfully with Traditional Owners and schools to design learning activities that are relevant and align with their values. This case study demonstrates how relationship building, mutual respect and understanding how to tailor learning to make content relevant can encourage active participation of Indigenous educators and students and support a reciprocal both ways learning environment.

ACM Reference Format:

Bev Babbage. 2024. Working at the speed of trust - respect, relevance, and reciprocity – encouraging participation with remote First Nations communities in Australia. In Asian CHI Symposium 2024 (Asian CHI 2024), September 19, 2024, Online, AA, Malaysia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 9 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3704611.3704615

1 INTRODUCTION

Over the past five years in my role as an Apple Professional Learning Specialist, I have been privileged to work with First Nations (or Aboriginal) people in very remote communities in Northeast Arnhem Land and the eastern Kimberley region, working on Apple's First Nations Education projects [1,2]. Working in schools, I designed and delivered professional learning on leveraging iPads and creativity to support First Nations educators and students. This involved working with community members, First Nations educators, non-Indigenous educators and students to co-design and co-create relevant and authentic learning activities. Building respectful relationships and trust was critical, engaging with communities in regular monthly visits and face-to-face learning on their Country and in their environment.

Apple Professional Learning Specialists are experienced educators and consultants who are endorsed by Apple to deliver professional learning, mentor and coach educators on the effective use of Apple technologies in teaching and learning. Authentically integrating iPad technology in supporting language and culture activities in remote Indigenous communities has been a rewarding learning curve. Many aspects need to be considered – traditional languages and culture, cultural protocols, fonts for sounds in Indigenous language, literacy levels, cultural safety, support from Elders and community, lack of connectivity, geographical remoteness and participants understanding, skills and prior experience with technology. Despite some hurdles and challenges, great success has been achieved with high participation of remote Indigenous educators and students in projects which allow them to see themselves in the curriculum.

These communities are located in some of the most geographically remote parts of Australia, some only accessible by off road vehicles for parts of the year or small planes. In Arnhem Land, these communities of Yolŋu people can be anywhere from 25 people to a few hundred, with some living in townships or on their traditional Homelands. All the communities I have worked with speak a dialect of Yolŋu Matha fluently and children are fortunate to learn Yolŋu Matha as their first language, meaning it is relatively strong. In the Kimberley, the desert communities were wider spread and I worked with Jaru, Kukatja and Walmajarri languages. These languages are considered vulnerable or endangered.

Upskilling the local Indigenous educators was one of the goals of working with remote Aboriginal communities. Indigenous educators can be known by various terms in different states, such as Aboriginal Teaching Assistant or Aboriginal Education Officer. Often, they are not trained teachers in the Western academic definition and are sometimes perceived as ‘teaching assistants’ or translators. However, these educators follow in the footsteps of their Elders, who had a rich tradition of intergenerational knowledge sharing successfully via oral transmission over millennia. They are the knowledge holders and tend to stay in the community, so these skills are not lost when non-Indigenous teachers are transient. Upskilling Indigenous educators involved observing, listening and providing targeted and contextualised professional learning tailored to their learning needs and goals. Empowering the First Nations' voice resulted in language and cultural activities that were relevant and culturally appropriate.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages are under threat [3]. Language is so intrinsically linked with culture, identity and knowledge that the loss of languages means so much more to First Nations Australians - it means the loss of millennia of history and ways of knowing, being and doing [4]. Communities and schools investigating technology as a strategy for supporting the learning of First Nations languages are often uninformed of the options available [5]. Understanding how iPads can best support student learning in some of these remote communities where students are still learning First Nations languages as their first language, may be able to inform strategies for language preservation and revitalisation in other communities.

In this research paper, I present a case study of collaborating with remote First Nations educators to make projects relevant and contextualised for their environment, as demonstrated with iPad projects in remote Australia supporting Aboriginal languages.

2 RELATED WORKS

Digital technology can be seen as both an enabler and a disruptor regarding First Nations language revitalisation, a so-called ‘double-edged sword’ [6]. However, during personal conversations with community leaders, I have often heard many Indigenous Elders express the view that they would like their young people to be equipped to confidently ‘walk in the two worlds’. Therefore, it is critical to both consult and work closely with First Nations language speakers and community leaders to understand their own views and beliefs, the context of their language use and how they want technology to be used.

Cassels & Farr [7] conducted a comprehensive study of 32 apps for First Nations language learning in North America. The findings draw parallels with my experiences. The study found that the advantages of mobile apps for Indigenous language learning included:

- Portability

- Reduction of Language Anxiety

- Offline usability

- Self-determination

- Fun and language prestige

Portability and offline usability are critical in very remote communities where phone and internet connectivity can be unreliable or non-existent. The ability to take iPads on Country for traditional learning, capturing photos and videos, and recording Elders speaking in traditional languages supports students in their cultural learning, without the need for connectivity. Upskilling community members with professional development supports self-determination, where communities can control content and develop their own pedagogical tools that are culturally relevant and contextually appropriate, empowering community-led learning.

Kral and Heath [8], in a study on adolescents and young men using GarageBand on a Mac desktop, noted some important affordances of the User Interface of the Apple software that is also applicable to iPad apps:

- Symbols and icons – “users, who previously would have avoided text-only procedures, to interpret, read and manipulate technology in socially relevant ways” (p. 231).

- Learning from observation, imitation and experimentation – they learned the GarageBand skills in similar ways to how they learn traditionally in the community, by watching and observing, imitating and experimenting, through trial and error.

- Multimodal learning – in addition to the icons, visual and textual elements combined with auditory elements provide rich learning experiences that support the learning process.

- Sequence of steps – repetition and memorising sequences is part of the iterative learning process [7].

Nordlinger et al. [9] also observed “the spatially-oriented and icon-based symbolic conventions used in many new media applications are enabling users (many with minimal or no literacy), to interpret, read and manipulate multimodal digital interfaces” (p. 6). The iPad and Apple apps' multimodal user interface create a safe user experience: the automatic saving of files and the ability to easily ‘undo’ combine to promote experimentation and reduce the fear of losing work or making mistakes. This experimentation and active participation in learning aligns with Yolŋu ways of learning.

3 METHODOLOGY

In Northeast Arnhem Land, there is a Yolŋu analogy about learning together, demonstrating the importance of doing together, in order to be able to talk together:

“You went hunting together. You talked

- before you went

- while you were there

- and when you returned” [10].

It is through talking and doing at the various stages of learning together that understanding can be improved through communication in a shared experience. Without knowing the analogy and pedagogy of this beforehand, this is how I have learned and worked alongside the Yolŋu educators in developing, co-designing and co-creating learning experiences and activities with iPad:

- talking before: We would discuss the learning outcomes they wanted to achieve in the lesson, what they were currently working on, whether it be a story, identity or seasonal-related theme, the vocabulary and how we would teach; whether I would lead or they wanted to lead the lesson. Critically, this was not just me doing the talking. This involved a lot of listening on my part, giving time for the First Nations educators to consider their responses.

- talking while: During the lesson, I model teaching with iPad and talk about things as they occur, such as how to undo a mistake or why I might choose a particular workflow. We look together at student work and observe the student behaviour, discussing as we go (where practicable).

- talking afterwards: we discuss the lesson - was it successful in their eyes? How could we improve it? Did the students effectively learn the iPad skills? How can we use the same skillset applied to a different learning activity? Do they feel confident to try it again without me? Has it linked well to their curriculum?

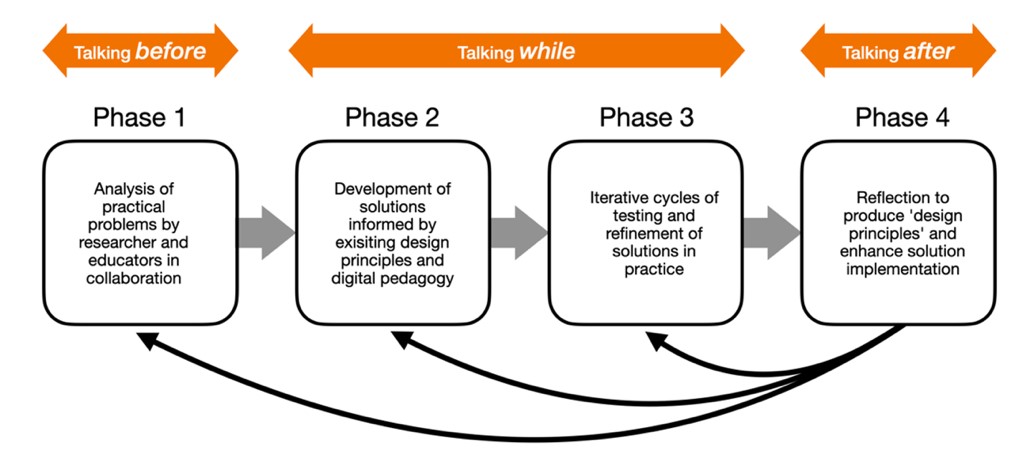

Inspired by Jackson-Barrett et al. [11] adopting Reeves’ Model of Design-Based Research (DBR) [12], I have adapted the model in the context of my research project and added the stages of learning together from the Yolŋu hunting metaphor (see Figure 1):

4 IPAD AND APPLE APPS

As I was working as an Apple Professional Learning Specialist, most of the apps used in the classrooms have been commonly available Apple apps, such as Keynote, Pages, iMovie and Clips. These also enable on-device usage without the need for internet.1 Emphasis was on creativity, so students and teachers could create their own content.

Given that most of the Indigenous educators had little or no experience with iPads, the first step was to demonstrate some of the possibilities to give context for learning the skills required. Demonstration activities were designed with contextualised examples, such as creating talking books with audio examples, animating drawings over photos, creating Clips videos with prompts using local languages, drawing over photos to show how to throw a spear, and creating multimodal visual dictionaries with audio, video, images and text. Once the educators saw the possibilities, they were excited to try the activities themselves. Initial hands-on activities were simple, with repetitive sequences of instructions to help instil the learning. There has at times been a fine balance between creating content for the teachers and teaching them to create by themselves. It is always the intention to help communities to tell their own stories, but it has been understood that there often needs to be a stimulus and example to demonstrate the possibilities, and that creating content is also part of the reciprocity.

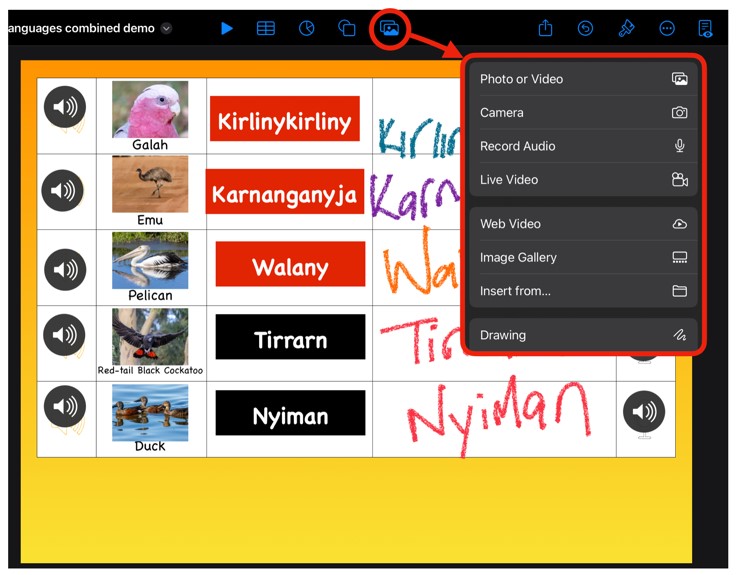

Apple's iWork apps, Keynote, Pages and Numbers, all have a similar user interface. Once teachers and students were accustomed to working with Keynote, the toolbar was familiar, and they were able to transition to Pages and Numbers easily. Importantly, the visual icons [8,9] in the toolbar make the app accessible to those who cannot easily read English. As can be seen in the Keynote example from Figure 2, the only text in the interface is the title. Even when tapping on the media icon for the other options, alongside the text, there are visual icons that can be referred to (Figure 2 inset). Similarly, Clips and iMovie apps use icon-based symbols and are easy to navigate. Literacy levels of remote Indigenous students can be low. Kral & Heath [8] observed that the use of symbols and icons in the user interface encouraged participation from those who might avoid text-based procedures. Icon-based navigation encourages confidence in experimenting with these apps. When instructing lessons, I show and refer to the icons with familiar names rather than the terminology.

4.1 4 Simple, versatile interface

Keynote has been the most used app for its simple interface and versatility. Beyond being used as a presentation tool, Keynote has been used for creating posters, animated videos, drawings, app prototypes and digital activities, such as the example in Figure 2.

4.2 4 Related to prior experience

This activity grew from watching two Indigenous educators teaching a lesson in Jaru language in the Kimberley. They were using a poster and flashcards and asked for suggestions in incorporating the iPads into their lessons. Following discussions, I created a quick table with columns in the background and locked these, so the students wouldn't move it by mistake. We used photos of the flash cards, drawings or ready-made shapes in Keynote for the visual stimuli. I created text boxes with the words pre-typed for students, as the primary goal of the activity was for the students to match the words from the audio with the correct orthography and the picture. It was decided that if students needed to type the words, it may be a challenge for some with their letter recognition and keyboard skills, as well as the potential for making errors. This activity kept the learning focussed on the language.

4.3 4 Students have fun and easy access

The lesson was a huge success, combining the iPad technology with authentic language learning in Jaru that engaged the students. The students were not restricted by their keyboard abilities, they could listen multiple times, easily dragged the text boxes and loved writing on the iPads with the Logitech Crayon (stylus). While some were shy at first to record their audio and moved to a quiet place, they enjoyed recording their own voices in Jaru and hearing themselves back. Students could listen multiple times to the pre-recorded audio and their own to compare and self-check for accuracy. (Later, an Elder told me how important they thought this was for students to hear themselves speaking in their traditional language.)

4.4 Using orality

In Japanese language, Hamada & Yanagawa [13] found a correlation between aural vocabulary and orthographic vocabulary in improved oral comprehension skills and his concluded that “language teachers need to focus more strongly on bridging the gap between aural and orthographic vocabularies". This supports the design of this activity. Adding multimodal functions such as audio or video to include the spoken language in digital activities, combined with the visuals of images and text, connects the written and spoken word.

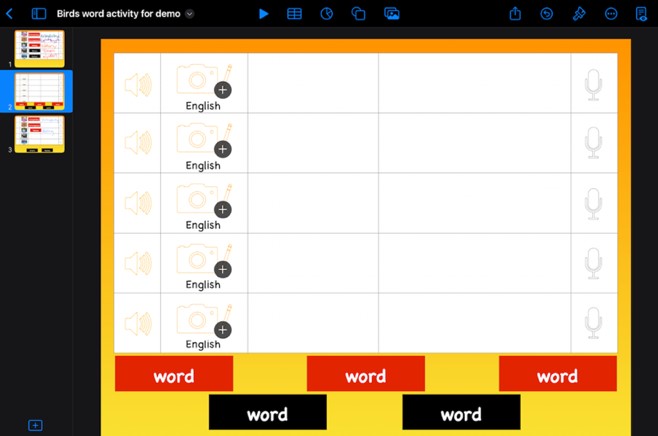

5 TEMPLATE DESIGN

Following multiple uses in various classes and schools over time, the initial Keynote activity has been refined, creating a Keynote Theme template. These templates are available for download from the Apple Education Community website [1]. For sustainability, ease of use is important so educators can create their own resources for ongoing classroom use. Creating templates provides educators with ready-made resources that they can easily adapt and replicate. Some educators requested no English on a page, whilst others preferred to have English. This can depend on the educational framework and model for teaching languages used by each individual school, or whether they are using it as an assessment, when they might prefer no visual cues and have students rely solely on the aural and textual component. The colours were chosen for the red, black and yellow of the Australian Aboriginal flag, but could be adapted for school colours or any preferences. The features used were:

- Placeholders - The plus symbols in the circles in Figure 3 are placeholders, allowing users to easily add their own photos, pre-formatted for the size and position on the slide.

- Text boxes - For text boxes, the educator double-taps and types the desired word in each box.

- Icons - The outlined images for audio and microphone were visual cues for placement of the audio icon. I use images and icons where possible instead of instructions to limit the written word on the page. Kral and Renganathan [14] noted the use of symbols and icons in software empowered students to learn from doing, regardless of their written literacy skills. Limiting the use of English text also aligns with some bilingual school approaches, where they do not want two different languages on the one page, to reduce issues with code-switching.

- Font - Visual details were considered, such as fonts that are easy to read for young learners or whether fonts supporting special characters such as ŋ or ṯ were required.

These activities have been used across multiple Australian Aboriginal languages, with vocabulary linking with a traditional story text studied, themes such as body parts and bush foods, and even phonemes and sounds. For the visual cues, if no photos are available, there are hundreds of Creative Commons shapes in Keynote or we have drawn images on the iPad and inserted them as an image. These Keynote files can be exported as videos to provide multimodal student samples and evidence. Some schools have also used these templates with their English literacy learning for CVC (consonant-vowel-consonant) words and vocabulary. This means the students can transfer the skills across multiple learning areas, so the use of the technology becomes embedded and they can concentrate on showing what they know.

This simple example shows the multimodal use of a common app, such as Keynote, with an activity that is interactive for students and utilises the functionalities of the iPad to record and listen to audio, which is so important with Indigenous languages, where transmission was traditionally oral.

6 DISCUSSION

There are a number of technical challenges in designing iPad-based educational applications to teach First Nations languages. I discuss some of these here to inform future designers on issues for consideration.

6.1 Connectivity

Having resources on device has been a solution to lack of connectivity, rather than Cloud or online storage. Using apps such as Keynote enables educators and students to create content on iPad, with no need for the Internet. AirDrop has been an incredibly useful tool for sharing photos, videos and Keynote templates, even in the remotest of locations, overcoming some of these challenges.

The difficulty in updating devices in some communities has meant that not all devices are on the same operating system or app update. This can cause challenges when demonstrating from devices when the UI looks different, especially when working with teachers and students who do not speak English as their first language, as they rely on visuals. Schools try to get iPads back to town for updating every term, and for myself, I often do not update my iPad immediately, so I have a similar version to the teachers.

6.2 Heat

For the most part, iPads have fared well in the tough conditions of remote Australia. All iPads have been protected with robust cases and transported in Pelican cases. However, the heat and humidity have taken their toll on the cases, and the devices have outlasted the cases. On several occasions, when outside, learning on Country in extreme weather, iPads have shut down with the heat. This suggests it probably means it is too hot to be outside for humans too. This has not been a critical issue.

6.3 Fonts

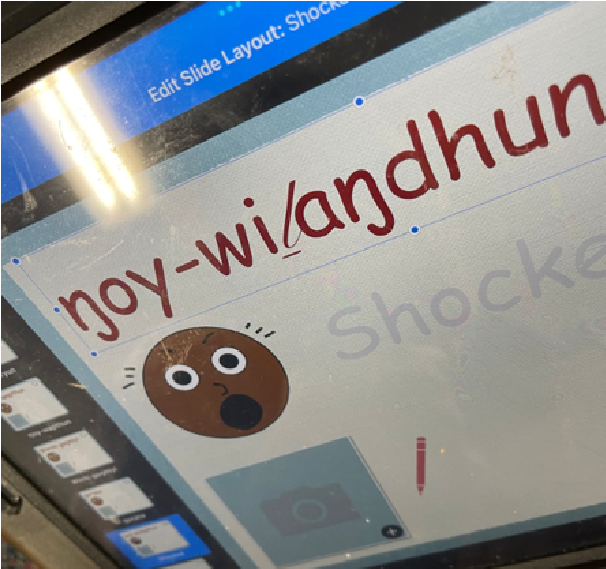

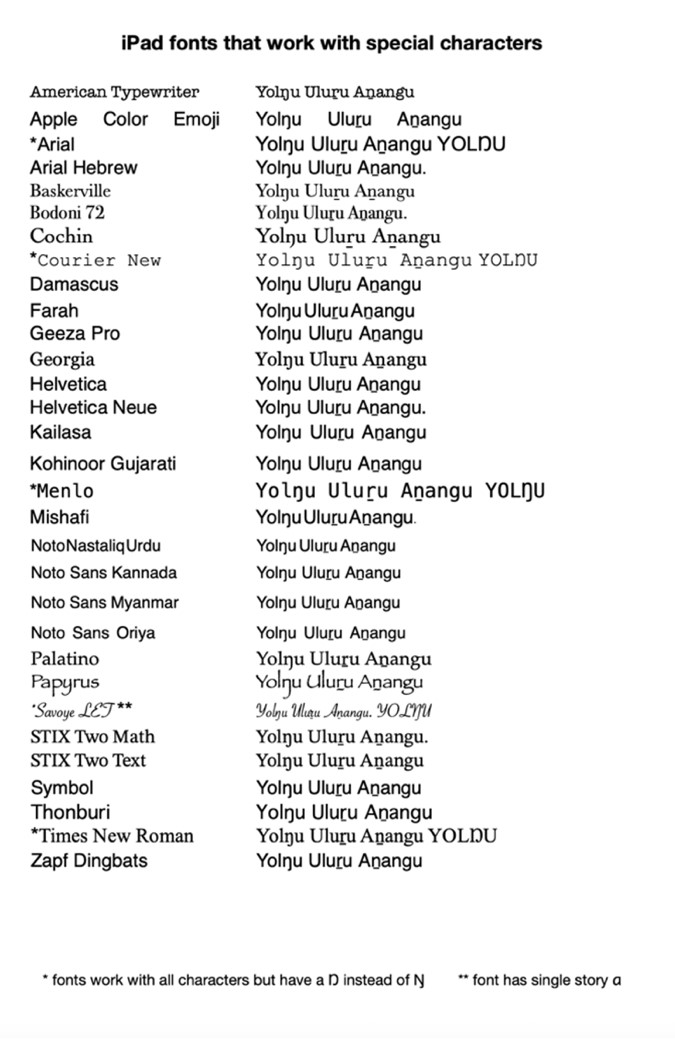

iOS15 saw the addition of special characters included in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages on the Australian keyboard on iPhone and iPad. This was a huge leap forward, allowing First Nations Australians, such as Yolŋu people, to be able to spell their names with correct orthography and enabling them to publish more easily. Yolŋu Matha is a general term for many clan languages spoken by the Yolŋu people. The ŋ in Yolŋu Matha (which looks like an n with a tail) signifies the ‘ng’ sound as in sing in English. Underlined letters represent retroflex sounds, where the tongue is placed at the roof of the mouth. The umlaut on the a, ä, means it is a long vowel sound, and the glottal stop, ‘, is an audible close.

YOLŊU ŋ ä ḏ ṉ ḻ ṯ and ' (glottal stop)

Whilst the addition of the characters in the Australian keyboard was welcomed, an issue that did arise was that not all standard iPad fonts work with these characters, as can be seen in Figure 4. I conducted an audit on fonts and compiled a list of fonts that do work with special characters (Figure 5); however, none of the easy-to-read fonts for young learners, with the single story ‘a’ and ‘g’, work with the special characters. Teachers have had to decide on whether a resource looks correct with characters or if it is easy to read for young students. This has been a frustration, only when working with languages with special characters, such as Yolŋu Matha. When working with Jaru, Kukatja and Walmajarri in the Kimberley region, this has not been an issue, but several other Australian and Torres Strait Islander languages do use special characters in their alphabets.

Understanding the issues arising from fonts was a result of listening to educators, collaborating with them and problem-solving. Researching, auditing fonts and looking for solutions are examples of reciprocity and were appreciated and respected by Yolŋu educators and linguists. Whilst still not yet completely solved, solutions are in progress. Andika AuSIL Font, a customized Unicode font that does work with the characters and is easy to read has been created by The Australian Society for Indigenous Languages [15]. However, Mobile Device Management (MDM) and downloading these to all iPads have proven challenging thus far.

These processes of problem-solving in a systematic and generic manner, taking into consideration the many variables that affect working in remote areas with people from different cultures and practices, are the basis for developing appropriate technology use.

7 CONCLUSION

These projects demonstrate that iPads can be successfully integrated into Indigenous language education, but that context and relevance is key. It is vital to have an understanding and respect of cultural protocols and as a wise man once told me, one must ‘move at the speed of trust’. Nothing can be rushed, and there is a need for flexibility, particularly when working in very remote communities. Professional learning needs to be contextualized and culturally appropriate, and all content must be relevant and applicable to their environment and curriculum to encourage participation. There is a strong desire to learn about technology, and Elders certainly share aspirations for their young people to be able to successfully ‘walk in two worlds’. However, culture and ceremony are always a priority, and sensitivity needs to be shown to be flexible and acknowledge this in all interactions. Once trust and mutual respect have been established in a both ways learning environment, my experience has shown that there is great potential in this space.

Acknowledgments

Following my experiences over the past 5 ½ years and in the spirit of reciprocity, I am currently a Masters by Research candidate at Charles Darwin University, researching the efficacy of iPads and Yolŋu Matha [language] to try and measure in some way the effectiveness and provide evidence-based research to schools and communities. This mixed methods research will rely heavily on qualitative data from research conversations and honours Indigenous methodologies. I would like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the lands on which I worked and the numerous people I have worked with over the years from the Yolŋu, Kukatja, Walmajarri and Jaru communities

References

- Babbage, B. (2022), Supporting First Nations languages with simple Keynote templates, accessible on Apple Education Community Forum, https://education.apple.com/resource/250010447

- Babbage, B. (2024), Supporting First Nations Languages with iPad - Apple ANZ Back to School 2024 Series - 1 of 3, accessible on Apple Education Community Forum, https://education.apple.com/resource/250012211

- Australian Government Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DITRDC). (2020). National Indigenous Languages Report. https://www.arts.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-indigenous-languages-report-lowres.pdf

- Nakata, N. M. (2023). Indigenous languages & education: Do we have the right agenda? The Australian Educational Researcher, 51(2), 719–732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-023-00620-0-023-00620-0

- First Languages Australia. (2014). Angkety map: Digital resource report. https://www.firstlanguages.org.au/angkety-map

- Galla, C. K. (2018). Digital Realities of Indigenous Language Revitalization: A Look at Hawaiian Language Technology in the Modern World. Language and Literacy, 20(3), 100–120. https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29412

- Cassels, M., & Farr, C. (2019). Mobile applications for Indigenous language learning: Literature review and app survey. Working Papers of the Linguistics Circle, 29(1), Article 1.

- Kral, I., & Heath, S. B. (2013). The world with us: Sight and sound in the “cultural flows” of informal learning. An Indigenous Australian case. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 2(4), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2013.07.002

- Nordlinger, R., Carew, M., Green, J., Kral, I., & Singer, R. (2015). Getting in Touch: Language and digital inclusion in Australian Indigenous communities. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4940.5924

- Northern Territory Department of Education. (1986). Team teaching in Aboriginal schools in the Northern Territory. Northern Territory Department of Education.

- Jackson-Barrett, E. M., Gower, G., Price, A. E., & Herrington, J. (2019). Skilling Up: Providing Educational Opportunities for Aboriginal Education Workers through Technology-based Pedagogy. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 52–75. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n1.4

- Reeves, T. (2006). Design research from a technology perspective. Educational Design Research, 52–66.

- Hamada, Y., & Yanagawa, K. (2023). Aural vocabulary, orthographic vocabulary, and listening comprehension. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2022-0100

- Kral, I., & Renganathan, S. (2018). Beyond School: Digital Cultural Practice as a Catalyst for Language and Literacy. In G. Wigglesworth, J. Simpson, & J. Vaughan (Eds.), Language Practices of Indigenous Children and Youth: The Transition from Home to School (First edition.). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-60120-9-1-137-60120-9

- The Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (n.d.), https://ausil.org.au/fonts/

Footnote

1Clips requires the internet to access a full range of stickers and text animations, but significant work can be done with the standard stickers available.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License.

Asian CHI 2024, September 19, 2024, Online, Malaysia

© 2024 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-1008-7/24/09.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3704611.3704615