Supporting Group Coursework Assessment in Large Computing Classes through an Open-Source Web Application

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3772338.3772348

CEP 2026: Computing Education Practice 2026, Durham, United Kingdom, January 2026

Group coursework in computing often suffers from uneven workload distribution, poor communication, and limited visibility for staff, especially in large cohorts. We present an open-source web application that addresses these challenges through automated team allocation (via genetic algorithms), student skill self-assessment, meeting tracking, peer review, and supervisor tools. The system is embedded in a year-long second-year undergraduate module on software design and development (with 300 students in 2025/26) and is replacing manual, ad-hoc processes with structured, data-driven support. Informal trials suggest it helps staff identify struggling teams early and supports fairer marking. Data collection from the first cohort is ongoing. We share findings, reflect on design choices, and discuss implications for adoption in other computing courses.

ACM Reference Format:

Sam Kitson, Adriana Wilde, and Richard Gomer. 2026. Supporting Group Coursework Assessment in Large Computing Classes through an Open-Source Web Application. In Computing Education Practice 2026 (CEP 2026), January 08, 2026, Durham, United Kingdom. ACM, New York, NY, USA 4 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3772338.3772348

1 Introduction

Group assessment in computing courses is widely recognised as problematic, particularly in large cohorts. Persistent issues include uneven workload distribution, poor communication, and limited progress monitoring. Existing practices for group formation, peer review and meeting tracking are manual and disjointed. We explain the importance of addressing these issues (section 2), and related work on group allocation and peer reviews (section 3). Our contribution builds on this prior research by adapting such ideas to a large institutional context, embedding them into curricula, and providing an open-source tool designed for practical deployment, presented in section 4. We also describe its context of application and a provide preliminary evaluation (section 5). We then offer some conclusions and future work (section 6).

2 Motivation

Soft interpersonal skills such as teamwork and communication are key employability factors [15] that may be seen as more important than the technical skills acquired at university [28]. Evidence suggests both are equally influential in determining salaries [3].

Many approaches exist for teaching soft skills in higher education, though group-based projects are common [9]. These can take many forms, ranging from informal seminar groups to year-long projects contributing a significant proportion of marks. Implementations across universities, subjects and individual modules vary wildly, and despite recommendations of best practice, there is little standardisation in how such activities are organised [11].

Beyond simply allowing students to practice interpersonal skills, group work offers other benefits, such as helping universities to manage rapidly growing cohorts [14, 21].

Despite its clear advantages, group work in higher education has many challenges. Most notable is social loafing, the reduced effort someone exhibits when working in a group versus working alone [18]. Social loafing continues to be observed in group-based assignments and can lead to conflict within the group [23]. The effect is known as free-riding, though some argue these are distinct, with free-riding being a consequence of social loafing and involving an active desire to gain credit without working [14].

A related phenomenon is the sucker effect: a form of social loafing that occurs when a group member believes other members lack effort. That member then reduces their own contribution to match what they perceive the effort level of the group to be [27]. Empirical evidence has shown it at work even in projects designed to involve the participants personally [26]. Together, these behaviors lead to dissatisfaction with performance within groups, which, in turn, causes frustration around the final grades [1]. Still, such experiences provide valuable learning experiences for students [6].

3 Previous work

Recent work [2] highlights current challenges around fairness, equality, and student attitudes toward teamwork in computing education, reinforcing the need for supportive tools that encourage positive collaboration while addressing perceived inequities. This adds to a body of work on collaborative learning and the use of systems for peer assessment, team allocation, and workload tracking. Existing studies demonstrate the potential of algorithmic approaches to support group formation and peer evaluations.

3.1 Group formation

A controversial part of group work is the allocation of students into teams. Three main methods typically [20] used are:

- Random selection: this simple method often creates groups unbalanced in terms of skill and leads to student frustration [17], though it can help them meet new friends [16].

- Self-selection: students can use existing knowledge of their peers’ work habits when choosing groups, which can increase trust [5]. However, this method is not authentic in business [4] and working with friends increases the likelihood of cheating [24].

- Algorithmic: automated group formation based on parameters such as academic performance, skills and personality is a promising active research area, discussed below.

There exist various algorithmic approaches for group formation subject to constraints. Craig et al. [13] use a variety of attributes, such as homogeneous (similar within groups), heterogeneous, and apportioned (close to the class average). An evolutionary algorithm is then applied. A similar study aimed to balance skills between groups, which produced promising results but did not address the challenge of collecting accurate skill ratings from students [22].

This highlights a challenge in existing work: defining the optimal group. Those diverse in ethnicity, personality and gender (among other attributes) may exhibit better creativity and innovation [25], but research shows that diversity may itself lead to free-riding [14]. Mixing students from individualistic and collectivist cultures is reported to cause conflict [24], though when combined with careful support, group projects may become a valuable place for them to learn from each other. Ultimately, the correct optimisations in group formation depend on the specifics of the subject, coursework, and students involved; an algorithmic approach may facilitate this.

3.2 Peer evaluations

A well-known tool to prevent free-riding is a Peer Evaluation System (PES). This involves group members rating each other's performance and the results may be used to determine final grades. Encouraging students to compare their contributions has been shown to increase motivation, and even just the knowledge that peer evaluations will occur has been observed to reduce free-riding [12]. Empirical evidence shows use of peer evaluation can lead to more positive student attitudes about group work [10].

There is no standard method for conducting peer evaluations, though several recommendations have been found in literature, such as a web-based system [8] in which students assess each other using both numeric and written criteria. Answers are then anonymised and reviewed by staff before being released to students. The system's use was studied over multiple semesters with the researchers finding a positive impact on student engagement. Another study [7] suggests that regular use in longer projects (in this case, every 4 weeks) reduces free-riding. This also gives under-performing members a chance to redeem themselves [1].

4 Our solution

Our contribution builds on this prior work by unifying these tools into a single system, facilitating a fairer assessment, better oversight, and earlier intervention when teams struggle. We developed an open-source web application (github.com/samuelkitson/group-coursework) to support group coursework management in undergraduate computing. Key features include:

- computerised team allocation using genetic algorithms;

- meeting tracking for accountability;

- structured peer reviews and skills self-assessments;

- automated insights about struggling students/teams;

- supervisor dashboards and tools.

The system replaces informal, ad-hoc processes with structured, data-driven support for students, staff and team supervisors at each stage of the coursework.

4.1 Genetic algorithms for allocation

Despite there being no optimal allocation strategy, interviews with educators revealed a common two-stage process; first creating groups based on data such as past performance or skills, then manually fixing problems such as groups with a lone female student. Our tool mimics this by allowing educators to define requirements specific to their assessments and then automatically finding groups that satisfy them. We combine this with previous work on using genetic algorithms [13] by simplifying how non-technical educators configure them; a key barrier to real-world utilisation.

Fundamentally, we abstract the fitness function used to score generated teams into criteria and dealbreakers. Criteria define ideal group traits, such as a wide spread of historic marks, and are combined using a weighted average. Dealbreakers are binary and prevent unwanted characteristics, such as groups with one female student. These are implemented with a drag-and-drop interface where criteria ordering represents relative weighting and arbitrary datasets can be uploaded by staff. Skills self-assessments can also be completed by students in-app and the results utilised here.

The genetic algorithm used can be summarised as:

- A population of 50 random allocations (with no duplicates).

- Each group allocation is evaluated using the fitness function (from the configured criteria and dealbreakers). The fitness of an allocation is determined by its lowest-performing group.

- Crossover of the highest-scoring allocations. Groups from two allocations are combined into one list and sorted by fitness, then sequentially added to an offspring allocation. Groups including students already allocated are skipped and surplus students randomly allocated at the end.

- Mutations, random students swapped between groups.

- The crossed-over and mutated allocations are combined with a small number of the best unchanged allocations from the previous round (elitism). The cycle repeats 20 times.

4.2 Meeting tracking

It has historically been challenging at our institution to encourage student engagement with new learning management systems. We addressed this by allowing students to record their team meetings within the app. This aims to promote engagement and minimise free-riding, as students are aware that staff monitor this data and potentially use it to inform marking.

Minutes can be recorded by and are visible to any team member. If a student disagrees with them for any reason, they are able to lodge a dispute to which staff can respond.

4.3 Peer reviews

Drawing upon the work described previously, we recognised the importance of regular, low-stakes peer reviews in providing evidence for persistent free-riding. Our approach, called check-ins, is to ask students to rate the relative workload in their team every week during the project, considering only their experiences in the preceding week. This aims to limit the effect of short-term problems (such as illness) on a student's overall scores; as data is gathered weekly, only their scores for that week will be affected and this will be easy for staff to identify.

Care must be taken when designing the user interface for such a tool; some student interviewees admitted that when using existing points-based systems (e.g. [8]), they inflate their own ratings without fully considering the contributions of others. To combat this, the check-in asks students to distribute effort points among the team (between one and seven each) to reflect perceived contributions. Each member starts with four points and a zero-sum constraint prevents points being added without being taken from somebody else (Figure 1). This encourages consideration about relative contributions and whether the student had to complete another's work. A similar approach has previously been effective [19].

Staff can also configure full check-ins for specific weeks, which ask students to rate each other in specific skills and provide a short review comment. These could inform marking or be released to students as appropriate for the assignment.

4.4 Insights and reports

The key benefit of combining the above functionality into a unified system is that the data is held centrally and can be used to generate detailed insights about student progress. This allows struggling students or teams to be flagged to staff, who can intervene and provide support before serious problems develop.

Various data points (such as meeting attendance and check-in scores) are analysed to generated insights about each team and made visible to staff and supervisors. For convenience, these are categorised by severity to allow teams with the most serious problems to be easily identified.

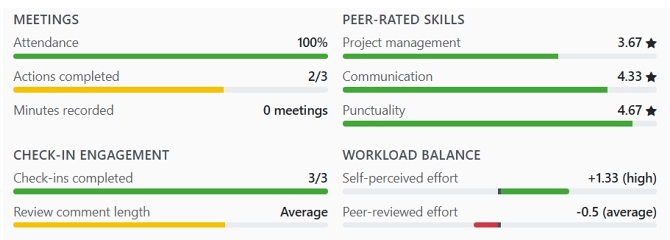

Detailed progress reports can be generated about teams to inform marking. Among other statistics, they compare students’ check-in scores for themselves compared to those received from others (Figure 2). This makes it possible for staff to deduct marks or investigate further when a student's self-reported effort differs significantly from the team's perception; an indicator of free-riding.

5 Context of application and results

The tool has been embedded into COMP2300, Software Design and Development Project, a year-long second-year undergraduate module, with 300 students in 2025/26. The module is project-based, requiring sustained collaboration across multiple deliverables. The application is integrated into students’ project workflow, and used by staff to monitor progress and provide targeted support. Initial trials within the department indicate promise. Students are optimistic that the tool could lead to a less uneven workload and a more enjoyable experience. Staff report that it helps identify struggling teams earlier than before and provides evidence for fairer marking. System data (i.e., longitudinal peer reviews, supervisor observations and meeting logs) offer richer insight into team dynamics.

A short initial study was conducted with 55 student participants, who completed an online questionnaire to understand their perceptions of group coursework. Three months later, and after a brief introduction to the app, 22 participants returned to access a personalised account with two example assignments. To mimic everyday interactions with the app, they were asked to complete a skills assessment, record minutes for a simulated meeting, answer a check-in and lodge a meeting dispute.

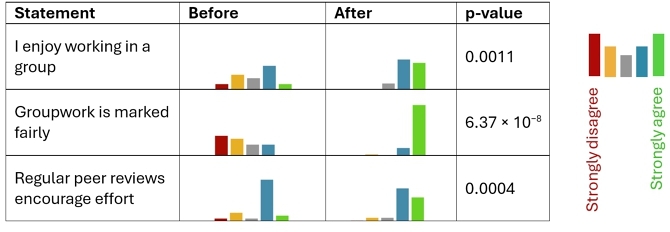

Nine Likert questions from the initial study were then repeated to identify changes, with the statements adjusted to ask how participants would feel if using the app for a real coursework. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied to the results and the significance value of 0.05 reduced to 0.00556 using the Bonferroni correction. Three statements saw statistically significant changes, each becoming more positive after exposure to the app (Figure 3).

Free text responses from the questionnaire and comments from a student focus group provide insight into these improvements. A recurring theme was that students felt reassured that the app gathers clear evidence in the event of free-riding, leading to increased accountability. One participant said it was:

“An exceptionally useful tool for holding people accountable for the work they promised to do.”

The meeting tracker was highlighted as effective for generating this evidence and simplifying the process of recording minutes. One student raised concerns about the integrity of meeting minutes if they can be edited following a dispute; in response, we implemented an audit log to track changes.

The check-in feature was well-received. Confidence in the ability of regular peer reviews to encourage equal effort increased after students completed the simulated check-in. Many participants commented positively on the zero-sum constraint, for example:

“Balancing points makes you think about the distribution of the workload more deeply since the setup stops you deducting points without reallocating them.”

Some participants were concerned that the simple numeric check-ins would be ineffective when no other team members had contributed, though this would be mitigated by staff enabling full check-ins and requiring students to provide a review comment.

Formal evaluation with the first full cohort is ongoing. Planned analysis includes comparisons between self- and peer-reviewed scores, and correlations between generated insights (e.g. attendance, review comment quality, etc) and project performance.

6 Conclusions and Future Work

This work demonstrates how structured, data-driven support for group work can be scaled to large undergraduate cohorts. It offers practical lessons for educators: which features are most useful, what data can realistically be collected, and how to embed such tools into existing assessment structures. As the system is open source, it has potential to be adopted and adapted by others in the computing education community facing similar challenges.

Our future work includes completing evaluation of the current cohort, disseminating results, and refining the tool. Planned enhancements include considering peer review data from previous semesters during allocation, additional feedback mechanisms, and integration with institutional learning management systems. We also aim to trial the system in other modules and disciplines, exploring scalability and transferability beyond computing.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on SK's undergraduate project (supervised by RG and supported by AW, both lecturers in COMP2300). We thank all the staff and student participants for their time in our study.

References

- Praveen Aggarwal and Connie L. O'Brien. 2008. Social Loafing on Group Projects: Structural Antecedents and Effect on Student Satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Education 30, 3 (Dec. 2008), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475308322283

- Cristina Adriana Alexandru. 2025. Group Assignments and Support Aimed to Develop Student Teamwork Skills and a Positive Attitude Towards Teamwork in Computer Science Higher Education. In Proceedings of the 9th Conference on Computing Education Practice(CEP ’25). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3702212.3702215

- Jiří Balcar. 2016. Is it better to invest in hard or soft skills?The Economic and Labour Relations Review 27, 4 (Dec. 2016), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304616674613

- Lyndie Bayne, Jacqueline Birt, Phil Hancock, Nikki Schonfeldt, and Prerana Agrawal. 2022. Best practices for group assessment tasks. Journal of Accounting Education 59 (June 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2022.100770

- Tim M Benning. 2024. Reducing free-riding in group projects in line with students’ preferences: Does it matter if there is more at stake?Active Learning in Higher Education 25, 2 (July 2024), 242–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/14697874221118864

- Jill Bourner, Mark Hughes, and Tom Bourner. 2001. First-year Undergraduate Experiences of Group Project Work. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 26, 1 (Jan. 2001), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930020022264

- Charles M. Brooks and Janice L. Ammons. 2003. Free Riding in Group Projects and the Effects of Timing, Frequency, and Specificity of Criteria in Peer Assessments. Journal of Education for Business 78, 5 (May 2003), 268–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320309598613

- Stéphane Brutus and Magda B. L. Donia. 2010. Improving the Effectiveness of Students in Groups With a Centralized Peer Evaluation System. Academy of Management Learning & Education 9, 4 (Dec. 2010), 652–662. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.9.4.zqr652

- Manuel Caeiro-Rodriguez, Mario Manso-Vazquez, Fernando A. Mikic-Fonte, Martin Llamas-Nistal, Manuel J. Fernandez-Iglesias, Hariklia Tsalapatas, Olivier Heidmann, Carlos Vaz De Carvalho, Triinu Jesmin, Jaanus Terasmaa, and Lene Tolstrup Sorensen. 2021. Teaching Soft Skills in Engineering Education: An European Perspective. IEEE Access 9 (2021), 29222–29242. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3059516

- Kenneth J. Chapman and Stuart Van Auken. 2001. Creating Positive Group Project Experiences: An Examination of the Role of the Instructor on Students’ Perceptions of Group Projects. Journal of Marketing Education 23, 2 (Aug. 2001), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475301232005

- Elizabeth G. Cohen, John I. Goodlad, Linda Darling-Hammond, and Rachel A. Lotan. 2014. Designing groupwork: strategies for the heterogeneous classroom (third edition ed.). Teachers College Press, New York.

- Debra R. Comer. 1995. A Model of Social Loafing in Real Work Groups. Human Relations 48, 6 (June 1995), 647–667. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679504800603

- Michelle Craig, Diane Horton, and François Pitt. 2010. Forming reasonably optimal groups: (FROG). In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM International Conference on Supporting Group Work(GROUP ’10). ACM, New York, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1145/1880071.1880094

- W. Martin Davies. 2009. Groupwork as a form of assessment: common problems and recommended solutions. Higher Education 58, 4 (Oct. 2009), 563–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9216-y

- Matthias Galster, Antonija Mitrovic, Sanna Malinen, and Jay Holland. 2022. What Soft Skills Does the Software Industry *Really* Want? An Exploratory Study of Software Positions in New Zealand. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM / IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement. ACM, Helsinki Finland, 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544902.3546247

- David E. Gunderson and Jennifer D. Moore. 2008. Group Learning Pedagogy and Group Selection. International Journal of Construction Education and Research 4, 1 (March 2008), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15578770801943893

- K. J. Hanley. 2023. Group allocation based on peer feedback. European Journal of Engineering Education 48, 2 (March 2023), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2022.2106191

- Bibb Latané, Kipling Williams, and Stephen Harkins. 1979. Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37, 6 (June 1979), 822–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.6.822

- Ruth E. Levine. 2008. Peer Evaluation in Team-Based Learning. In Team-based learning for health professions education: a guide to using small groups for improving learning (1st ed ed.), Larry K. Michaelsen (Ed.). Stylus, Sterling, Va, 103–111.

- Evangeline Mantzioris and Benjamin Kehrwald. 2014. Allocation of Tertiary Students for Group Work: Methods and Consequences. Ergo 3, 2 (2014). https://ojs.unisa.edu.au/index.php/ergo/article/view/924

- Alistair Mutch. 1998. Employability or learning? Groupwork in higher education. Education + Training 40, 2 (March 1998), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400919810206884

- Ravneil Nand, Anuraganand Sharma, and Karuna Reddy. 2018. Skill-Based Group Allocation of Students for Project-Based Learning Courses Using Genetic Algorithm: Weighted Penalty Model. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering (TALE). IEEE, Wollongong, NSW, 394–400. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE.2018.8615127

- Regina Pauli, Changiz Mohiyeddini, Diane Bray, Fran Michie, and Becky Street. 2008. Individual differences in negative group work experiences in collaborative student learning. Educational Psychology 28, 1 (Jan. 2008), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701413746

- Janice Payan, James Reardon, and Denny E. McCorkle. 2010. The Effect of Culture on the Academic Honesty of Marketing and Business Students. Journal of Marketing Education 32, 3 (Dec. 2010), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475310377781

- Amin Reza Rajabzadeh, Jennifer Long, Guneet Saini, and Melec Zeadin. 2022. Engineering Student Experiences of Group Work. Education Sciences 12, 5 (April 2022), 288. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12050288

- Tina L. Robbins. 1995. Social loafing on cognitive tasks: An examination of the “sucker effect”. Journal of Business and Psychology 9, 3 (March 1995), 337–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230973

- Mel E. Schnake. 1991. Equity in Effort: The “Sucker Effect” in Co-Acting Groups. Journal of Management 17, 1 (March 1991), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700104

- I Made Suarta, I Ketut Suwintana, Igp Fajar Pranadi Sudhana, and Ni Kadek Dessy Hariyanti. 2017. Employability Skills Required by the 21st Century Workplace: A Literature Review of Labor Market Demand. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology and Vocational Teachers (ICTVT 2017). Atlantis Press, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.2991/ictvt-17.2017.58

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

CEP 2026, Durham, United Kingdom

© 2026 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-2121-2/26/01.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3772338.3772348