Voice Assistants for Mental Health Services: Designing Dialogues with Homebound Older Adults

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3661536

DIS '24: Designing Interactive Systems Conference, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark, July 2024

The number of older adults who are homebound with depressive symptoms is increasing. Due to their homebound status, they have limited access to trained mental healthcare support, which leaves this support often to untrained family caregivers. To increase access, a growing interest is placed on using technology-mediated solutions, such as voice-assisted intelligent personal assistants (VIPAs), to deliver mental health services to older adults. To better understand how older adults and family caregivers intend to interact with a VIPA for mental health interventions, we conducted a participatory design study during which 6 older adults and 7 caregivers designed VIPA-human dialogues for various scenarios. Using conversation style preferences as a starting point, we present aspects of human-likeness older adults and family caregivers perceived as helpful or uncanny, specifically in the context of the delivery of mental health interventions, which helps inform potential roles VIPAs can play in mental healthcare for older adults.

ACM Reference Format:

Novia Wong, Sooyeon Jeong, Madhu Reddy, Caitlin A. Stamatis, Emily G. Lattie, and Maia Jacobs. 2024. Voice Assistants for Mental Health Services: Designing Dialogues with Homebound Older Adults. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS '24), July 01--05, 2024, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark. ACM, New York, NY, USA 15 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3661536

1 INTRODUCTION

Older adults (aged 65 and above) who require significant effort to leave their homes due to physical illnesses or injuries can be considered homebound older adults [23]. In the United States, the number of older adults who are homebound continues to grow, increasing from 5 percent in 2011 to 13 percent in 2020 [2]. These adults frequently rely on family caregivers, often spouses and adult children, for physical health and general wellbeing support. Caregivers commonly assist with tasks such as transportation, grocery shopping, and medication administration [60]. However, supporting older adults’ mental health is often overlooked, despite 44% of homebound older adults experiencing depressive symptoms [27, 100]. Many home-bound older adults often lack access to evidence-based mental health interventions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)1 [3], behavioral activation (BA)2 [65], and reminiscence therapy3 [35]. Although telehealth has become more available, there still exists a huge gap between the supply and demand for mental health providers [47] to provide either in-person or remote mental health treatments for homebound older adults. This unfortunately leads many family caregivers, who are not professionally trained, to manage older adults’ mental health symptoms, which potentially results in improperly managed mental health symptoms in homebound older adults [68, 71]. This is particularly problematic because unmanaged mental health symptoms can further complicate their other health conditions. Furthermore, family caregivers often experience emotional burnout themselves [30, 60] affecting their ability to provide this type of support. Therefore, there exists a need for scalable and inexpensive evidence-based mental health services for homebound older adults.

In recent years, technology-based mental health interventions, such as mobile applications, social robots, and VIPAs have been developed to help manage mental health symptoms [1, 5, 70, 73, 83] by delivering CBT through psychoeducation, mood and symptom tracking, and skills development [50]. Among these tools, the low-cost VIPAs, such as Apple Siri, Google Home, and Amazon Echo, show promising potential to help deliver mental health services longitudinally in home at a large scale due to their natural voice-based mode of interaction [43, 45, 63] , which can mitigate some common challenges older adults experience when using other tools (e.g., difficulty with texting on small mobile interfaces) [8, 31, 33, 101]. In fact, VIPAs have been increasingly adopted by older adults [39], especially those who are socially isolated and homebound because they can provide companionship through conversations [22, 59, 64].

Most existing works that explore older adults and VIPAs focus on task-oriented interactions, such as searching for information, learning the time and weather of the day, setting alarms and reminders, and playing music [20, 43, 59, 63, 64, 84], and little research is done on how VIPAs can be used to deliver evidence-based mental health interventions. Compared to brief mood-improvement activities (e.g., playing music) [95], a mental health intervention requires longitudinal involvement and continuous structured interactions. For a VIPA to effectively deliver mental health services to older adults and engage them over long-term interactions in the home context, several challenges will need to be addressed, including VIPA's speech recognition ability [67] and improved usability [31]. While many factors affect the usability of technologies (e.g., perceived usefulness [18]), conversational styles for verbal exchanges (e.g., use of questions [88], word choices and expressions [89]) are unique to VIPAs usability. Most past research (e.g., [9, 36, 43, 59, 64, 105]) relied on experimental design or observation to study older adults’ preferences in conversation styles. Few studies (e.g., [19, 57, 77]) have involved older adults and family caregivers as designers to ensure VIPA conversation styles align with older adults’ needs, preferences, and values.

In this paper, we investigated homebound older adults’ preference in VIPAs’ conversation styles in order to increase their engagement with long-term mental health interventions through VIPAs. For older adults, it has been found that they have different preferences for different situations [21, 49, 97]. As such, designing appropriate conversational styles for mental health interactions that meet the needs and expectations of older adults is important [75, 79], especially considering the sensitive and personal nature of disclosing emotions and behaviors. Among the different aspects of conversational style, the incorporation of human-like traits has been recommended by past research for health-related interactions [37, 42, 80]. The concept of anthropomorphism can help assess older adults’ preferences of human-like traits in VIPAs, yet little work has been done with older adults to understand how a different context (i.e., mental health) may affect their preferences. Therefore, we asked three research questions:

- How do homebound older adults and family caregivers perceive the degree of human-like traits displayed by a voice assistant when engaging in mental health interventions?

- How do homebound older adults and family caregivers envision using VIPAs to support older adults’ continuous mental health management?

- What concerns do homebound older adults and family caregivers have regarding using VIPAs for mental health interventions?

To answer these questions, we worked with 6 older adults and 7 family caregivers in one-on-one co-design sessions to conceptualize human-VIPA interactions. We included caregivers’ perspectives because caregivers play a crucial role in managing older adults’ physical and mental health and we envision that a VIPA would facilitate communications between older adults and their caregivers by providing both just-in-time support and enabling in-home health monitoring. The methodology of designing dialogues has been previously used as a co-design method to understand user preferences and needs in interacting with voice-based technology [11, 44, 96], and thus we chose to use a similar task to ideate older adult-VIPA interactions for in-home mental health intervention delivery. In our study, older adults were provided with a number of scenarios (greetings, goal setting, routine reminders, etc.) to design their conversations with an imaginary VIPA. In our study, we considered older adults’ needs as co-design participants, in which Lindsay et al. [51] found the older adults may experience more difficulty brainstorming new technologies or nonexistent features without probes or prior experiences. Thus, we adapted the dialogue design method for homebound older adults and family caregivers and included probing materials to increase engaged participation. Our findings showed nuances in preferences of specific aspects of anthropomorphism in VIPAs, including emotions, empathy, and liveliness. This allowed us to gain a better understanding of what VIPA characteristics older adults and family caregivers perceive as appropriate for mental health-related interactions. This study is one of the first to involve older adults and family caregivers as designers alongside the researchers to design VIPAs specifically for mental health use. The contributions of this paper intersect research on VIPAs for older adults and VIPAs for mental health:

- Deepen the understanding of conversation stylistic preferences of mental health dialogue exchanges between VIPAs and older adults, emphasizing perceived empathy and autonomy

- Identify the roles VIPAs can play in delivering mental health services collaboratively with caregivers or individually for homebound older adults.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Older Adults and VIPAs

Over the years, the HCI community has developed VIPAs to support older adults’ general wellbeing, studying approaches to incorporating VIPAs into older adults’ daily living routines [40, 77], and examining old adults’ current use of VIPAs to identify benefits and challenges [16, 19, 31, 45, 64]. Features commonly used by older adults were transactional and task-oriented (i.e., "getting things done"); in particular, the most used features include retrieving information, such as current time and weather, setting alarms and reminders, and launching entertainment services such as music streaming and listening to audiobooks [16, 43, 59, 63, 64, 84]. Some older adults also engaged in small talks [59] as they naturally would with humans [42, 43, 63, 64].

Compared to other smart devices such as computers and smartphones, VIPAs require lower adoption effort because voice-based interactions are similar to how people communicate and interact with one another [31, 42, 43, 45, 63]. Although VIPAs may present accessibility issues for older adults with auditory impairments [43, 61], relying on voice as the primary mode of interaction generally can mitigate other challenges older adults experience due to mobility and visual impairments [33, 42]. Older adults have also reported that they are more confident using VIPAs as opposed to other devices, and they enjoy the playfulness aspect of interacting with VIPAs [16, 86]. However, older adults may stop using VIPAs because they fear that using smart technology (e.g., turning on light switches at home) would diminish their ability to care for themselves or complete household tasks independently [45, 90], are unclear about VIPAs’ values and benefits for them [15, 42, 59, 90], have difficulties operating the device [15, 43], and are concerned with privacy [16, 37, 42, 90]. While most VIPAs are more affordable than alternative options (e.g., social robots and computers), the cost may be a barrier for a subset of the older adult population with lower socioeconomic status [61]. Furthermore, one of the most notable challenges arises from the VIPAs’ capabilities to process and understand natural language. Older adults’ speech tends to get slower, with more long pauses reflecting changes in their cognitive states [16, 24, 38, 58], causing VIPAs to dismiss or interrupt older adult users’ requests and responses [37, 99]. Other language-related issues may include older adults’ speech clarity and varying pronunciation [37, 42, 43, 59, 84]. In Harrington et al.’s study [34], Black older adults explained that they had to code-switch when interacting with VIPAs; they frequently adjusted their speech style from using African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) to a style (e.g., shorter, more formal) that would be understood by Google Home. Although several studies have investigated how older adults use VIPAs in the current technological state, little work has been done on conceptualizing how older adults might use VIPAs in daily lives for mental health support if they were capable of natural multi-turn dialogues and high level of socioemotional intelligence.

2.2 VIPAs for Mental Health

VIPAs can support individuals’ mental health in various ways: when experiencing stressful situations, users can request mindfulness activities such as breathing exercises and meditation, as well as soothing music to be played [64, 69, 81]. Studies have also explored using VIPAs for self-reported data collection around mood and activities of daily living [53, 54]. The anonymity and nonjudgmental characteristics of the technology prompted users to disclose more symptoms and personal information compared to a traditional assessment [52, 54, 55], leading to more implementation of mental health screenings through VIPAs [25, 52, 69].

Older adults in particular have expressed interest in using VIPAs for health and wellbeing purposes [57, 80]. They are open to receiving recommendations from VIPAs to engage in health and wellness activities [34, 91] and tracking positive behaviors and emotions [10]. They use VIPAs to retrieve information related to their physical health (e.g., their illnesses and symptoms, medication, nutrition, and vital signs [9, 34]) and to schedule medication intakes for managing chronic illnesses [63]. With regards to mental health, VIPAs can be used and perceived as companions that can provide emotional support for older adults in social isolation [20, 22, 43, 59, 63] by acting as “someone” who is nonjudgmental and always available to talk in the moment of need. Existing research focused on older adults’ mood-boosting activities via their everyday usage of VIPAs, or explored how conversational agents are used to deliver evidence-based mental health interventions, such as CBT, to the general population [29].

Additionally, family caregivers of homebound older adults assist with not only daily activities such as transportation but also physical health [60, 71], mental health management, and emotional support [60]. Because of the vast responsibilities they have, they experience extreme burnout [30, 60, 82] and lack peer support during the process [82]. As such, VIPAs could be a tool to complement their care through existing features such as playing music to improve older adults’ mood [20, 63], as well as monitoring and tracking older adults’ physical health and medication intake [20, 31, 57].

Therefore, our work aims to explore how VIPAs can potentially increase access to evidence-based mental health interventions for homebound older adults without a clinician's presence, considering the specific design requirements and considerations made for this population and how VIPAs can support remote caregivers facilitate their older adults’ mental health care.

2.3 Designing Conversations between Older Adults and VIPAs

When designing conversation between older adults and VIPAs, it is crucial to consider the level of anthropomorphism, or human-likeness, of VIPAs. Although its definitions varied, anthropomorphism refers to attributing a non-human object "humanlike properties, characteristics, or mental states" [26]. The level of anthropomorphism influences users’ future interactions with the nonhuman agent [26]. Specifically for VIPAs, characteristics such as the agent's voice gender and tone can influence users’ perceptions and level of engagement [28] and expectations of VIPAs’ capabilities [15]. In the older adult population, those who experience social isolation tend to anthropomorphize VIPAs more, [33] often refer to the agent as a friend or “she/her” pronouns, and favor a polite and friendly conversational style from VIPAs [22, 31, 36]. As such, older adults generally prefer using polite expressions that follow typical social norms when interacting with VIPAs, such as thanking the devices for answering a question [42, 43]. Similarly, Taggart et al. [87] found that older adults sometimes project their emotions and relate to socially interactive agents. They found that older adults in a nursing home behaved as if they were building relationship with a zoomorphic social robot that express various emotional states, and the robot's animal-like behavior led to increased engagement. However, this could be influenced by the physical form of the robots that mimic pets or other lifeforms, which begs the question of authenticity in human-machine relationships [92, 93]. Unlike social robots, smart speakers do not typically have a life-like physical design, which makes studying conversational styles more crucial.

Although limited work has examined VIPAs’ conversational styles in delivering mental health services, studies on both health-related VIPAs and text-based chatbots have found conflicting results. Older adults expect conversational agents to exhibit competency in finding health-related information when conversing about health [46] and perceive the agent that uses a formal tone to be more appropriate and competent [21]. Yet, some also consider it as less human-like and lacking empathy [21, 22] and express preferences for a warmer and friendlier personality [9, 46]. Additionally, in a review of Amazon Alexa Skills, Shin and Huh-Yoo [81] found that people were more satisfied when the VIPA was more anthropomorphized. To assess anthropomorphism, past research often referenced pronouns that users labeled the agent (e.g., “she”, “my friend”). Some also attributed feelings and human-like behaviors to the agents, especially older adults who saw the agent as a companion. They may ask the agent questions they would normally ask acquaintances, such as whether the agent has a significant other [42]. Yet, these measures do not necessarily indicate preferences of VIPAs’ human-likeness [66]; Pradhan further highlighted that little is known if other characteristics of VIPAs also affect older adults’ preferences. For example, the use of expressive language could be another characteristic that should be explored.

Yet, little work has examined older adults’ preference for the VIPAs’ conversational styles when engaging in mental health intervention delivery and its role in such services. Unlike in most task-based interactions, such as retrieving weather forecast information or streaming music, treating mental health conditions requires engaging patients over long-term interactions with special considerations for their health and socio-emotional needs. As a result, more research is needed when anthropomorphizing VIPAs’ designs for mental health purposes [75, 85].

3 METHODS

We conducted 90-minute participatory design sessions with 13 older adults and family caregivers to answer our research questions. This section further describes the design activity used to generate our findings and the process of data collection and analysis.

3.1 Recruitment and Participants

We recruited older adults and caregivers in the U.S. through research registries, such as ResearchMatch4, local senior and community health centers, and the university-affiliated health system for outpatient geriatrics and general internal medicine. Email advertisements and letters were distributed to provide details of the study and contact information. Once a potential participant expressed interest in participating in the study, a research assistant on the team performed an eligibility screening via phone calls. For homebound older adults, the eligibility criteria included the following: (1) 65+ of age, (2) having experienced symptoms of depression, (3) having received emotional and physical support from a family caregiver, and (4) showing no signs of dementia through a cognitive test [13]. Participants were not required to disclose any physical ailment such as motor or visual impairment. For family caregivers, participants must (1) be at least 18 years old and (2) have provided weekly unpaid support to an older adult with a history of depression. Caregivers were recruited to provide an additional perspective as part of the older adults’ immediate care team.

Although participatory sessions are traditionally done in-person, we chose to provide both the option to participate in-person (i.e., at the University or at their home) or virtual. The rationale of this decision was both in consideration of the homebound nature of our participants and the geographical reach of recruitment. When asked, all participants chose to participate in the study virtually. Consent was collected verbally during the screening process. A total of 6 older adults and 7 family caregivers (n=13) participated in the study. Table 1 details participant demographics, including their experience with voice assistants (i.e., smart speakers, mobile voice assistants). Family caregiver participants were not related to the older adults who participated in the study, but they all were either spouses, adult children, or siblings of the older adults they supported. Participants received $50 for their participation in this study.

| Participant | Role | Age | Gender | Experience with VIPAs | Supported by/Supporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA1 | Older adult | 67 | Female | Mobile | Spouse (co-located), adult child |

| OA2 | Older adult | 80 | Female | None | Adult child (co-located) |

| OA3 | Older adult | 66 | Male | Smart speaker, mobile | Spouse (co-located) |

| OA4 | Older adult | 67 | Male | Smart speaker, mobile | Spouse (co-located) |

| OA5 | Older adult | 67 | Male | Smart speaker, mobile | Spouse (co-located), adult child |

| OA6 | Older adult | 84 | Male | Smart speaker | N/A |

| CG1 | Caregiver | 59 | Female | Mobile | Older sibling |

| CG2 | Caregiver | 35 | Male | None | Parent |

| CG3 | Caregiver | 52 | Female | Smart speaker | Parent (co-located) |

| CG4 | Caregiver | 71 | Female | Smart speaker | Spouse (co-located) |

| CG5 | Caregiver | 71 | Female | Smart speaker | Spouse (co-located) |

| CG6 | Caregiver | 57 | Female | Smart speaker | Parent |

| CG7 | Caregiver | 38 | Female | Smart speaker | Parent |

3.2 Procedure

We conducted 13 co-design sessions via Zoom, where each participant participated in a 90-minute session in a one-on-one setting with either the first or the second author. All sessions were video recorded, and individuals from a university-approved third-party transcription service transcribed the audio data for analysis purposes. For answering the research questions listed, co-design is a useful method because it allows participants to openly create their ideal version of a technology, directly communicate their preferences based on their personal experience. Co-design aims to "produce new knowledge as people develop and experiment with (new) ideas around a matter of concern" [103]. As such, the range and specificity of co-design activities vary depending on various factors, including the participant population (e.g., older adults) and their health conditions (e.g., those with visual impairments).

Although limited activities have been used to study human-voice assistant interactions, several prior works have used dialogue trees and dialogue designs to explore how children and adults would interact with voice-based devices [11, 44, 96]. Similarly, in our sessions, participants completed a dialogue design activity where they drafted conversations between a voice assistant and themselves for six to seven different scenarios (Table 2) centered around behavioral activation as a sample evidence-based mental health intervention. Behavioral activation intervention is commonly used by mental health professionals to help older adults plan and encourage them to participate in pleasurable and rewarding activities to manage their depression [65]. The scenarios were chosen based on existing sample behavioral activation protocols provided by mental health providers on the research team, in which they guide the interactions providers had with their patients. Because participants might not be familiar with participatory design as a research method or writing dialogues, we used the first scenario, Greeting, as a practice scenario for participants to familiarize themselves with the activity.

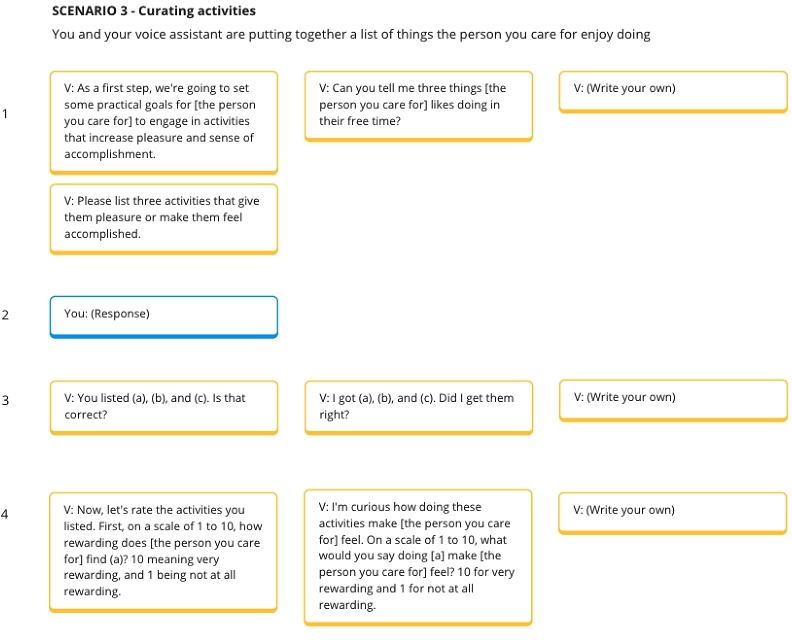

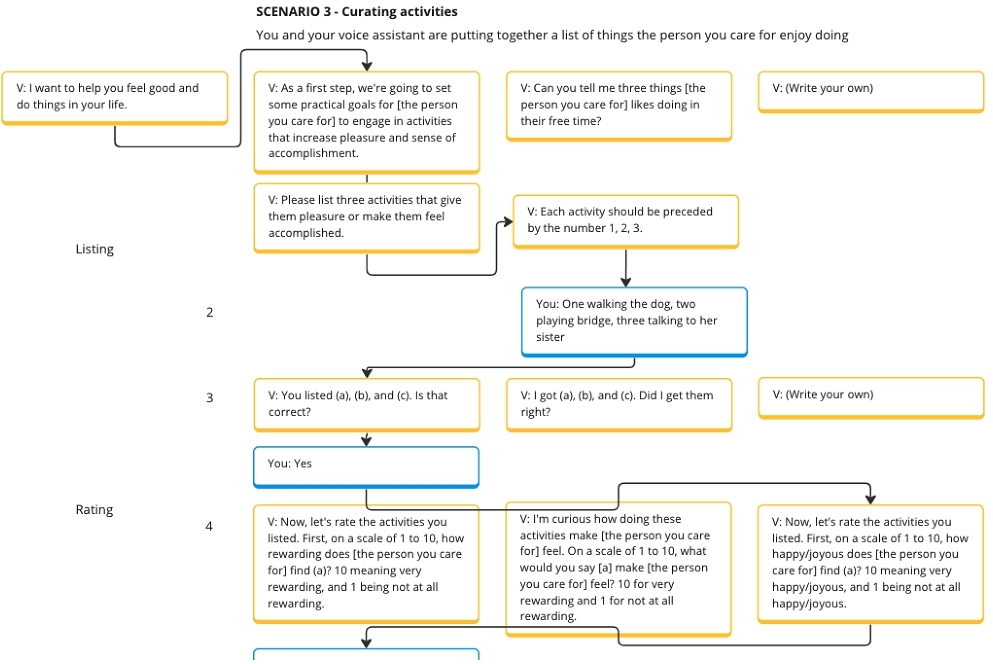

In each session, the researcher shared their screen to show different virtual dialogue trees for each scenario. The materials for the activity were designed and stored on an online whiteboarding tool, Miro 5 . For each scenario, the research team prepared two example dialogues the voice assistant could say to the participants, with one being more formal (e.g., “Now, let's rate the activities you listed. First, on a scale of one to ten, how rewarding do you find (a)? Ten meaning very rewarding, and one being not at all rewarding.”) and another being more casual through more expressive language (e.g., “I'm curious how doing these activities make you feel. On a scale of one to ten, what would you say doing [a] make you feel? Ten for very rewarding and one for not at all rewarding.”). Participants were also asked to create their own or rewrite the dialogues as they desired. Figure 1 shows an example of the initial dialogues provided for a caregiver in scenario 3, where caregiver participants were asked to help curate pleasant and rewarding activities for the older adults they supported using VIPAs. By default, the researchers read aloud the example dialogues for both older adult and caregiver participants. It is worth noting that one participant requested to read through the text on their own instead.

Because the aim of the design sessions was to involve older adults and caregivers as designers when creating technology to support their mental health and routines, the dialogue variants were designed to facilitate ideation and acted as probing materials [103] to encourage participants to think aloud about their ideal interaction(s), rather than being experimental. In fact, participatory design and co-design studies with older adults commonly relied on probing to generate feedback on prototypes [6, 46, 76] because older adults have shown to be more comfortable with discussing their life experiences as opposed to generating abstract new ideas [51]. Therefore, throughout the session, the facilitator regularly reiterated the purpose of the co-design activity. When some older adult participants began to provide answers to the assessment-based questions in the scenarios instead of designing dialogues, the researchers took notes of their responses then refocused them on the dialogue design.

Furthermore, the researchers intentionally probed the participants to re-write the dialogue options when participants showed hesitation and uncertainty about the example dialogues. Participants were then asked to provide a rationale for the dialogues they chose or wrote for each scenario. We also recorded other data generated in the design sessions on Miro, including the responses participants gave to answer questions asked by the VIPA in each scenario and the ordering of dialogues. The word choices and language participants drafted as part of the activity were used to understand how older adults and caregivers would prefer to interact with a VIPA for mental health intervention use. Figure 2 shows an example of the rewritten version of the example dialogues seen in Figure 1. The participant first added an introductory dialogue for the VIPA to initiate the conversation. They then wrote new dialogues using word choices and styles (i.e., the right most yellow card labeled "V:" in each row) they preferred instead of choosing the example dialogues.

| Scenario | Older Adult | Caregiver |

| 1 | Greeting: You and your voice assistant are greeting each other to start the interaction. | Greeting: You and your voice assistant are greeting each other to start the interaction. |

| 2 | Introduction: You and your voice assistant are getting to know each other. | Introduction: You and your voice assistant are getting to know each other. |

| 3 | Curating Activities: You and your voice assistant are creating a list of activities that give you pleasure and a sense of accomplishment. | Curating Activities: You and your voice assistant are putting together a list of things the person you care for enjoys doing. |

| 4 | Goals and Reminders: You and your voice assistant are discussing when you would like to do these activities. | Goals and Reminders: You and your voice assistant are discussing when you would like the person you care for to do these activities. |

| 5 | Suggestions by Caregivers: Your voice assistant alerts you that your supporters have suggested new activities. | Tracking and Assessment: You and your voice assistant are tracking and assessing the progress toward these activities. |

| 6 | Reminders: Your voice assistant reminds you of the activities on your list. | Reporting: Your voice assistant is showing you an aggregated report of the activities completed by the person you care for and their moods. |

| 7 | Tracking and Assessment: You and your voice assistant are tracking and assessing the progress towards these activities. | N/A |

3.3 Data Analysis

We analyzed the transcripts using inductive thematic analysis [7]. This provided further insights into the rationale behind the participants’ design decisions and the specific word choices used in rewriting the dialogues, as well as their perceptions of the dialogues used as probing materials. Three members of the research team developed two code books (one for the older adult data and another for the caregiver data) using a bottom-up approach, identifying codes that emerged from the study data. After two iterations of the codebooks and an additional round of re-coding the initial transcripts, the three team members reached a consensus on the codebooks. Subsequently, the remaining transcripts were distributed among the same three members where they finished the coding process using the established codebooks. They also held weekly discussions to identify conflicts by reviewing each other's codes and write analytic memos. Example codes included “Voice assistant is too human-like”, “Greeting voice assistant”, and “Data sharing between older adult and caregiver”. The researchers then generated themes based on the codes, including “autonomy and control” and “preferences for voice assistant conversational style”. Themes were then used to organize the Findings in this paper.

3.4 Ethics and Privacy

This study was reviewed and approved by the university's ethical review board (Institutional Review Board). Participant information was collected during the phone screening and each participant was assigned a participant ID to anonymize their identity throughout the study. All recordings, demographic and contact information are stored on a university-encrypted server with restricted access to only the research team. Study data on Miro is anonymized using participant IDs. The research team interacting with the participants also received training on risk assessment.

Two caregiver participants experienced the loss of the person they were supporting within the past year. The research team reached out to the participants prior to the session to inquire about the participants’ comfort level in continuing participation. During the session, we asked if it would be appropriate to bring up past memories with their loved ones, and provided a space for sensitive conversations where they could share memories and experiences of loss as needed, as recommended by Sakaguchi-Tang et al. [74]. Participants also had the option to discontinue the session at any time.

4 FINDINGS

Overall, both older adults and family caregivers displayed similar behaviors and conversation preferences when designing VIPAs dialogues for behavioral activation. In this section, we focus on how users perceived VIPAs’ role in mental health intervention delivery through different levels of anthropomorphism displayed by VIPAs. Then, we attend to both older adults’ and family caregivers’ perspectives on how dialogue-based interactions can provide social and emotional support. Finally, we describe the need to respect older adults’ autonomy and privacy in conversational-based mental health interventions with VIPAs.

4.1 Anthropomorphism, Emotional Expression, and Colloquial Language Use in VIPAs

One of the challenges in conversation design for VIPAs is determining the level of anthropomorphism of the agent that is contextually appropriate for the task it is engaging in with users. In our study, we found that all participants used anthropomorphic language in the conversation design task but showed varied levels of preferences in the use of colloquial languages. In most scenarios, participants chose to use direct and short language for the agent's utterances, especially when the task was focused on delivering the behavioral activation intervention through the VIPA. They commonly chose dialogues or wrote their own that were straightforward and simple instead of ones with pleasantries. For instance, during the Goals and Reminders scenario, participants were given two examples of possible VIPA utterance, (A: “Would you like to set weekly goals for these activities?” and B: “Now that I know what you/they like doing, I want to know how often you/they would want to do them. Would it be ok if we talk about that?”). Six participants preferred option A and two rewrote the dialogues because the pleasantries in option B felt inauthentic and off-putting.

Although participants shared different reasons for their preferences against pleasantries, the most common reason was the mental model of VIPAs being an artificial intelligence instead of a person, an object rather than a sentient technology. One caregiver said, “‘Thanks for sharing that.’ I don't think it needs to go into too detailed of being empathetic because [...]‘Whoa! You're not a person. What are you trying to say to me?’” (CG7). Because a VIPA is not perceived as a person, participants felt that they did not need to uphold the social responsibility to “have dialogue or a conversation with it” (OA5). Furthermore, participants perceived certain word choices to be violating their mental models of insentient technology. Common phrases that led to negative reactions from participants include VIPAs expressing an emotion such as being excited (e.g., “I'm excited to work with you for the next 16 weeks.”) and curious (e.g., “I'm curious how doing these activities make you feel.”). One older adult thought that it was “kind of silly for a digital assistant to say, ‘I'm excited,’ because it's a machine. How excited can it be?” (OA4). Similarly, a caregiver commented that the VIPA could not be curious because it was an AI, and it was merely “gathering this data ‘cause [it's] programmed to” (CG2). As such, emotional expression that would anthropomorphize the VIPA was consistently perceived as pretentious. Particularly, participants strongly disliked VIPA's comment of “that's a great name” when participants initially shared their name with the VIPA. Because participants understood that the VIPA “is AI, so that's programmed in there” (CG5), which seemed “kind of patronizing” (CG5) when VIPAs made such comments. Instead, participants chose the more direct response (i.e., “Thank you.”) that proceeded to the next interaction. In the same scenario, some participants chose to anthropomorphize the agent, attributing feelings and human-like colloquial language use to the VIPA. However, differences existed; while some participants felt that the VIPA was “a little too perky, like it's trying too hard” (OA4) and “trying to get on [their] good side” (OA3), which felt inauthentic, one participant felt that emotional expression represents “a more casual type of a statement” (CG4).

Despite critiques toward the VIPA prototypes in some scenarios, participants expressed a desire for the VIPA to use friendly and colloquial languages in other scenarios. For example, when presented with two options introducing behavioral activation (A: “My goal is to help you to learn about behavioral activation technique which focuses on using behaviors to activate pleasant emotions. It has been shown to improve depressive symptoms.” and B: “I'm really interested in learning about how to help people feel more positive and came across this technique called behavioral activation. Want to hear more about it?”), one caregiver commented that she option B was “more colloquial, more conversational, as opposed to a little more formal” (CG5), which was more inviting to use with older adults. An older adult compared the more formal languages to VIPAs “assess[ing them] like a psychiatrist or something” (OA2). Although a more formal language may be more clinically appropriate for delivering evidence-based mental health service, this older adult felt that receiving an evidence-based mental health service through VIPAs should not be the same as speaking with a mental health professional or taking a mental health questionnaire. The desire for informality may be related to participants wanting VIPAs to maintain a natural flow of conversation while keeping the dialogues brief and straight to the point. Most of these interactions stemmed from the participants’ habitual interactions with other people. As a result, when VIPAs greet the users, older adults expect a friendly greeting because that mimics how their typical greeting interaction is like: “when I greet someone, I like to say ‘Good Morning.’ It seems more natural to have that. A sound effect isn't quite there” (OA3).

Some participants displayed contradictions in their conversational preferences. For example, OA33 previously stated that they “don't want to have a conversation with artificial intelligence” (OA1), but later said they “want it to be flowing all the time – real easy conversation kind of thing” (OA1). To resolve this tension, one participant designed their dialogues in a scaffolding approach, starting with questions that were “a little more basic, and not so intimidating when you're just starting to do that” (CG7). Others provided concrete examples of how this could be achieved. When presented with the Tracking and Assessment scenario where the VIPA conducted a progress check with the participant (A: “After you did not complete the activity, have family time, how do you feel?” and B: “I want to check in with you to see how you're feeling after not having family time. Can you tell me how you're feeling?”), an older adult rewrote the dialogue to be “Are you okay with not having family time tonight” (OA5). This aligns with other participants’ preferences for shorter, more direct, and less clinical language that does not suggest VIPAs having emotional expression while maintaining the interpersonal characteristics of a conversation. In sum, while participants anthropomorphized the agent at times, they also recognized the agent was non-human and found the use of overly-human-like language use to be unpleasant.

4.2 VIPA Reduces Perceived Caregivers’ Burden

VIPAs can offer social and emotional support for older adults not only by being a companion but also a listener and a personal entourage, thus lowering the burden and reducing the responsibilities caregivers may experience when caring for their family members. Older adults in our study saw the VIPA as a useful tool for emotionally expressing themselves without worrying about burdening their caregivers. They valued VIPAs’ inability to be hurt and the ability to provide nonjudgmental responses during moments of depression and hardship: “I will snap back at it. It's easier to snap back at it than to snap back to my husband or somebody else” (OA1). Interestingly, OA1 followed up by sharing that they did not actually expect a response from the VIPA, stating that “She's grouchy. Leave the lady alone” (OA1). Other older adults also appreciated the mere presence of VIPAs and did not expect responses from the agent in similar situations. This is because older adults mainly wanted an outlet to express themselves and were aware of VIPA's limitations as a machine. OA5 provided a specific example in which they could not “get in touch with their friends and doing something with them” (OA5). Although frustrated, they explained that they would tell the voice agent about their frustration and what happened, but they “don't expect Alexa to really do anything about it” (OA5). The mere act of telling VIPAs about their feelings act as an emotional outlet for older adults in the study. Because of that, participants chose to have the VIPA simply acknowledge their feelings with generic language (e.g., "Thank you") or no response at all.

Additionally, anhedonia and overall low motivation and energy are common depression symptoms. As a result, depressed older adults may struggle to come up with pleasant activities, which is a challenge to implementing behavioral activation treatment. One of the scenarios (i.e., Curating Activities) in the study included probes that asked the participants to list pleasant activities they would like to engage in, during which one older adult stated that “list[ing] three activities that give [them] pleasure or make [them] feel accomplished” is a “difficult question to answer” (OA6). Instead of placing this additional responsibility on caregivers who may already feel taxed, caregivers particularly believed that VIPAs can support older adults by providing recommendations based on their preferences, physical conditions, and mood data. Namely, caregivers recommended that VIPAs could suggest and provide guided mindfulness activities or “a deep breathing exercise” (CG6) when older adults are “having a very anxious day” (CG40) or simple activities to get the person started” (CG1). Older adults and caregivers felt that this approach could provide social support without suggesting that the VIPA has emotional agency.

Furthermore, in the Tracking and Assessment scenario where the VIPA checked on the user's progress on activity goal-completion, participants often rewrote the dialogues to support emotion processing. Particularly, if older adults reported that they were unable to complete an activity as planned due to depression, responses from VIPAs should be “empathetic” (CG2) rather than being “a homework checker” (CG7). Participants suggested that the VIPA can offer words of encouragement that do not compromise their mental model of the technology. For example, VIPAs could acknowledge the hardship and encourage participants to try again: “Okay. You can try again tomorrow” (OA2). VIPAs could also ask if the older adults would like to hear a joke (“Would you like to hear a joke to cheer up?” (OA3)) or affirmations, such as “Great job” (CG1) and “I'm glad that you did [activity]” (CG7). Caregivers believed that VIPAs could provide social support to motivate older adults to complete activities for mental health intervention. This is crucial to behavioral activation, which uses behavioral goal setting to activate elevated mood among patients who struggle to find intrinsic motivation to engage in pleasurable activities.

4.3 Preserving Autonomy and Privacy in VIPA-mediated Mental Health Interventions

Autonomy and privacy are important topics to consider when creating technologies, so special considerations should be placed on preserving these two components in human-VIPA dialogue exchanges. In addition to the existing research on autonomy and privacy in VIPAs, our findings provide additional insight into the similarities and differences in priorities of user autonomy and privacy between older adults and family caregivers, especially when using VIPAs for mental health data collection and data sharing.

4.3.1 Autonomy. Both older adults and caregivers agreed that VIPA's features and conversational styles should allow older adults to maintain agency and independence when making decisions about their own mental health management. They noted that the role of the VIPA should be to support older adults, not supervise or monitor them, and the overall interaction should be a collaborative process. Participants suggested that it would be inappropriate for a VIPA to use patronizing or demanding languages; “don't want it to sound like [VIPA]’s in charge of my life. I like for it to give me options” (OA1). Similarly, caregivers acknowledged that despite needing physical support and help with transportation and errands, older adults are “still very independent” (CG6). Therefore, it is important to avoid “making [them] feel like [they're] being checked up on all the time” (CG6). Instead, VIPAs should empower them and help to maintain their independence through a more suggestive approach, making “[older adults] feel involved with the process; not that [the caregiver] was bossing [them] around or something” (CG1). In the Suggestions by Caregivers scenario, one participant wrote, “Do you want me to add the suggestions to your activity list?” (OA6) instead of having the VIPA automatically add the recommendations suggested by caregivers.

A specific example provided by participants is supporting flexibility in goal-setting, which is a common task in many evidence-based mental health interventions (e.g., behavioral activation). In both probing dialogue options presented in the Goals and Reminders scenario, the VIPA prototype was rigid and asked the users to provide both the number of times per week expected to progress toward the activity goal, as well as the specific time of day to do so. However, older adult participants described their lifestyle as unstructured and preferred it to be that way. Also, because mental health can vary on different days, caregivers also felt that there would be instances when older adults may already be engaging in pleasurable activities on their own: “she reads all the time every day [...] Off and on throughout the whole day and night” (CG1). Therefore, it is important to “let [the older adults] choose how they want to allocate” (CG5) time spent on activities.

4.3.2 Privacy. Although older adult participants generally agreed that it is beneficial to share mental health and activity data with their caregivers, they had strong preferences for maintaining fine-grained control over how their data was shared. They were particularly concerned about VIPAs announcing information when other people were physically present in the same space and sharing potentially private activity information with others. They also preferred providing consent at every point of sharing with caregivers as opposed to providing a one-time consent that would cover all cases. They explained that their preference may change from day to day and activity to activity, so they could avoid sharing “potentially embarrassing” (OA4) activities. Also, if they deemed the situation as trivial or caregivers would not be interested in learning the information, they would choose to not share the data: “if you don't think your supporters would be interested, then you just don't bother” (OA2). Therefore, when asked, participants all chose and designed dialogues that supported providing options (i.e., "Would you like to share [data] with your supporter?") as opposed to VIPAs announcing the data sharing was taking place.

On the other hand, caregivers were more concerned with the type of information that would be collected and the level of security of data storage. Several caregivers stated that the privacy policy and the rationale for data collection need to be transparent during the dialogue exchanges. A participant added a disclaimer at the beginning of the interaction: “We need this information for X, Y, Z purposes to customize this, this information will not leave the device, will not be used for marketing purposes” (CG2). Since engaging in evidence-based mental health services may involve sharing older adults’ data with a third party (e.g., clinical team), another participant also commented, “if somebody were monitoring the data, I would be curious how they were gonna use it” (CG1), but did not make direct design changes to the dialogues. By explaining why certain data is needed and how it will be used at every step of the conversation, we can improve transparency. This allows caregivers to be more likely to trust VIPAs and encourage their older adults to use the technology for mental health interventions.

5 DISCUSSION

The findings suggest that homebound older adults and family caregivers are receptive to using VIPAs for mental health interventions, and several VIPA characteristics and features could potentially increase older adults’ engagement with VIPAs: engage older adult users in short but informal conversations that are friendly and not overly-clinical, create a space for older adults to express themselves emotionally, without concern about burdening others, and support autonomy and privacy of mental health data and management during its dialogue exchanges with older adults.

We acknowledge that while many of the findings may also apply to text-based conversational agents, VIPAs provide unique opportunities to increase accessibility to evidence-based mental health services for homebound older adults with visual and motor challenges. Therefore, in this section, rather than comparing the two modalities (i.e., text vs. voice), we turn our attention to discussing the need for variations in conversational designs for mental health support and the roles VIPAs can play in the larger mental health system for homebound older adults, including a possible challenge to balancing engagement and clinical needs for mental health.

5.1 Designing for Anthropomorphic Conversational Styles for Mental Health is Nuanced

One of the main challenges in developing conversational agents is to design engaging conversational interactions that are appropriate for the interaction's purposes and contexts. Researchers across different domains have generally found that anthropomorphism in VIPAs leads to increased engagement. Yet, users’ preferences also depend on the context [66] of the interactions and the perceived benefits of incorporating human-likeness characteristics [41]. Epley also theorized factors such as the need for social connection and perceived similarity can further affect individuals’ anthropomorphism of nonhuman agents [26]. Our findings provide additional evidence and explanation for such variations, such as the unresolved tension of perceiving the VIPA as both object-like and human-like throughout their interactions.

In behavior change contexts, VIPAs that use polite and suggestive languages [104] and high-emotion have been rated more likable [29, 105]. Other studies further suggest that users often view computers as social actors (i.e., CASA paradigm [62]), and emotional connection can lead to increased trust in the computer and its likability [49, 62]. In contrast, our older adult and caregiver participants found emotional and affective expressions to be unnatural of a nonhuman agent, which conflicted with their mental model of VIPAs as objects (i.e., an information retrieval and data collection tool). As such, they described themselves as lacking interest in anthropomorphizing the VIPA. However, because a voice-based interaction closely mimics a natural human-human conversation, specific conversational characteristics for mental health conversations were still perceived as valuable as the situation calls for such traits (e.g., empathy). These two seemingly conflicting perspectives therefore created a dissonance internally among our participants.

5.1.1 Embed empathy into conversations. Our conversations with participants showed that they value specific traits that they value for mental health context, namely empathy and humor. Anthropomorphism is theorized to be higher when individuals desire social connections [26]. A prior study on VIPAs also found that older adults perceived VIPAs as social actors only if they desired companionship [66]. Similarly, participants in our study did not like the idea of VIPAs acting as if they had their own agency and feelings; however, at the same time, they designed dialogue exchanges that indicated empathy through its use of language. This was observed particularly after situations where older adults disclosed their depressive state or goal completion. Older adults and caregivers both believed that empathetic responses from VIPAs were needed as follow-ups. For older adults, anthropomorphizing the VIPA may be appropriate when social and emotional support is crucial to motivate them to engage in mental health interventions or provide companionship. In contrast, many participants frowned upon anthropomorphizing the VIPA during the more task-based interactions, such as when the VIPA is administering a questionnaire or guiding an older adult through a goal-setting activity based on behavioral activation protocol. This finding contrasts with findings from previous research in which older adults anthropomorphized the VIPA (i.e., expecting to have a similar conversation flow as they were talking with a human administering the questionnaires) when answering questionnaires through VIPA. Our findings align with those from a study done with South Korean college students, where efficiency was preferred over human-like pleasantries in transactional context [41]. This suggests that more research is needed to understand how VIPAs can deliver mental health services, including mental health questionnaires, without sounding either too object-like or human-like.

5.1.2 Support rapport building. Mental health support requires establishing rapport between two people, such as between an older adult and their therapist [102]. Being overly familiar at the start of a relationship diverges from the natural progression of rapport building from being more formal to friendly [17]. Therefore, our participants’ shifts in preferences for anthropomorphism in VIPA-human conversations may be influenced by rapport building. They commonly noted that the VIPA did not know them well, and they viewed VIPAs as machines or artificial intelligence that should not be anthropomorphized. This is similar to the early stages of a human-human relationship (e.g., acquaintance) in which it would be uncomfortable to engage in extended conversations. In fact, other studies also found preferences for acquaintance-like conversational styles [17] during the early stages of older adults’ interaction with VIPAs. Although they were not specific to mental health services, older adults built rapport with their VIPAs by asking grounding questions about the agent (e.g., favorite activity) [64]. Clark [17] suggests that a long-term interaction between a human user and a voice agent may require ongoing social conversations and rapport-building activities. When users’ expectations and beliefs about a nonhuman agent are violated, they rethink and adjust the anthropomorphism of the agent [15, 26, 41]. As such, the delivery of evidence-based mental health services may be more engaging if a scaffolding approach is used to foster engagement and an ongoing relationship. As designed by some of our participants, this scaffolding approach can begin with a simple, acquaintance-like style that aims to build rapport with the user through relational interactions. For example, when a VIPA tracks an older adult's activity goal completion as a part of behavioral activation, it can start the interaction by asking simple get-to-know-you questions (e.g., “What is your favorite color?”). Gradually, as the users become more receptive to anthropomorphizing the VIPA, it may even begin to disclose information about itself, which can increase engagement in conversations about highly sensitive topics [49].

Previous studies have also found that personality differences [97] and roles assigned to VIPAs by older adults [36] affect their preferences. These studies categorized users into different user groups and associated unique VIPA personas with each group. However, based on our findings, this perspective may be limiting. Instead, designers should consider a more personalized and nuanced approach to designing conversational interactions with older adults. In delivering evidence-based mental health services, this may be having fluidity to both support a more simple and formal style for psychoeducational resources and regular mental health assessments, as well as having a more empathetic and anthropomorphic style when talking about personal or sensitive matters, such as older adults’ moods and feelings. Caregiver participants in our study and college students from a past study [15] shared the same sentiment regarding personalization, which suggests that a nuanced conversational design approach may also be applicable to the general population. A past study has made a similar recommendation, in which VIPAs should be contextually aware so they could flexibly adjust their conversational styles when interacting with older adults [22]. In sum, to accommodate different users’ needs and preferences, VIPAs need to learn to vary their conversational styles depending on different contexts and factors (e.g., the interaction's purpose and user moods). We need further work to assess whether long-term engagement in an evidence-based mental health service that incorporates rapport-building through VIPA would further influence older adults’ preferences for anthropomorphism.

5.2 Role of VIPAs in Mental Health Interventions: Continuity of Care

Continuity in care is crucial in mental healthcare, which includes not only informational continuity (e.g., access to patient's information), but also management (e.g., flexible goals and services based on patient's preferences) and relational continuity (i.e., ongoing relationship between the patient and their care team) [32]. VIPAs have the potential to provide continuity of care through (1) data collection and data sharing, and (2) social and emotional support. The unique nature of VIPAs being always available and in between being perceived as more “human-like” despite being an “object” [66, 95] allows them to fluidly switch between these two labels, potentially leading to developing a different relationship with VIPAs than with their human care teams.

5.2.1 Continuous data collection in real-world settings and data sharing. Because neither the clinicians nor family caregivers can be continuously physically present with the homebound older adults, they are limited to relying on observation and recollection by the older adults for mental health support for older adults. In contrast, VIPAs allow for natural monitoring and real-time data collection of older adults’ mental health outside the clinical setting. This can help provide additional information about how patients feel and behave without placing additional burden on family caregivers to formally track their mood and activity engagement. In fact, both our older adult and caregiver participants liked the idea of conversing with VIPAs to regularly track moods and behaviors. Some even expressed the preference for open-ended answers over discrete choices (e.g., “yes/no”, “rate your mood”), so that they could provide additional details about their mental health.

Ongoing data collection by VIPAs also provides an opportunity for older adults to track positive health data (e.g.. “feeling good”) without relying on older adults to remember and manually document their moods or activity levels, which is data that older adults have previously expressed to see more in health data tracking [10]. Also, unlike text-based conversational agents, VIPAs are equipped with the technology that could potentially support emotion recognition by detecting tones, prosody, pitches, and speed of older adults’ voices [14, 37, 48]. However, older adults may view emotion recognition by technology to be intrusive [91], and emotion recognition technology may not be accurate. As future VIPAs detect changes in moods and activity levels, the agents can prompt the users for self-reflection and allow users to inform VIPAs of their mental health statuses. For example, VIPAs can proactively ask the users how they are feeling when detecting changes in speech patterns. This may further help users to develop emotion awareness through self-reflection and set the stage for implementing proactive strategies for managing mental health symptoms earlier in the course of symptom onset.

Additionally, managing older adults’ mental health requires a collaborative approach [32, 72]. Besides mental health professionals, their informal caregivers and primary care physicians are also a part of the care team. Since older adults often practice self-management to improve their mental health, caregivers and clinicians may not be able to provide the necessary support without proper data. This creates a need for a system that supports efficient sharing among different stakeholders, especially of data collected in a natural, real-world setting. VIPAs have the potential to connect patients and health providers [9]. Our findings further affirmed that VIPAs also have the potential to connect older adults with their caregivers. By providing additional data that clinicians and caregivers may not typically have access to, VIPAs can help support better and more holistic mental health service delivery.

However, both our study and past studies [10, 61, 94] identified privacy and autonomy concerns around data sharing without consent or without user's awareness. Turow further suggested that smart speaker companies may exploit user data such as audio clips and search history to manipulate users [94]. For our older adult participants, non-consensual data sharing is especially concerning for situations in which they had previously agreed to share data with their caregivers but wanted to change at the moment. To mitigate this concern, the older adult participants recommended increasing their autonomy, requesting VIPAs to check their data-sharing preferences at every instance of sharing. Caregivers also emphasized the importance of VIPAs providing clear and transparent information on mental health data usage directly addressing concerns around lacking awareness of data privacy and usage policy identified from past research [4]. Other research also supported the need for older adults to remain independent when using technologies [91]. Yet, two points of tension may exist when we attempt to support autonomy to users regarding data sharing. Particularly, granting older adults’ wishes to maintain autonomy in deciding when to share data conflicts with caregivers’ and clinicians’ needs to provide a safety net for older adults with depression. This is because older adults with depression may experience anhedonia or use unhealthy coping mechanisms that their care team should be aware of. Only if the data is made available to the older adults’ care team, then they can support the older adults’ mental health and make necessary adjustments to their routines. Future research should further explore how to balance the user's need for autonomy, efficiency, and the clinical benefits of using VIPAs to collect and share mental health data.

5.2.2 Active social and emotional support. Older adults and caregivers in our study conceptualized future social and emotional interactions with VIPAs, in which they proposed the possibility of having VIPAs using collected personal data to assist in behavioral change and mood improvement. For example, if an older adult expresses depressive symptoms in conversing with the VIPA, the agent can provide subsequent emotional support by telling jokes, recommending self-care activities, and offering words of encouragement. While past research [59, 64] also acknowledged VIPA’ role in providing social and emotional support for older adults, ours specifically pinpointed at its role to support older adults’ mental health without feeling as if they are burdening their caregivers.

Furthermore, VIPAs can encourage self-disclosure through their anonymity and nonjudgemental characteristics [49, 52, 54, 55, 93] and the act of self-disclosure was also observed in our study. In fact, participants desired the ability to disclose information in length, particularly around negative situations (e.g., the reason they could not complete a goal). While this could be attributed to anthropomorphism where participants compared disclosing information to VIPAs to disclosing information to other humans, the advantage of VIPAs’ inability to be upset or annoyed suggests that self-disclosure to VIPAs may foster perceived social and emotional support via VIPAs. Older adult participants expressed that it would be easier for them to share emotional experiences and intrusive thoughts with a VIPA instead of burdening their family members and friends, which further supports the social and emotional support older adults and caregivers perceive from VIPAs. This could be a new form of emotional processing and self-reflection in a journaling-like style, which has been shown to help improve mental health [56].

However, it is important to note that both our participants and others brought up privacy concerns about conversing with VIPA in shared spaces [90], especially when disclosing sensitive information such as mental health. Unlike the concerns discussed in the previous section, participants were concerned about information privacy that may be caused by the primary mode of interaction with VIPAs (i.e., voice). Therefore, dialogue designs for VIPAs need to consider ways to preserve privacy while providing social and emotional support. Namely, VIPAs should avoid announcing or broadcasting user's personal information without user's input. Instead, VIPAs may prompt users to initiate a social interaction to ensure the time and setting are convenient and appropriate for the users.

6 LIMITATIONS

The method used in this study is limited to designing dialogue exchanges between the human user and the voice agent. Other factors such as VIPAs’ tones and speech pacing were not explored in the present study. These factors can further influence the perceived VIPA's fluency in conversing, which subsequently affects how older adults interact with VIPAs [98]. Although these are important design considerations [78], using VIPAs to deliver mental health interventions is still relatively underexplored. Thus, we chose to focus on what participants would prefer to hear from VIPAs and say to VIPAs. Although conducting the activity via Zoom accommodated participants’ preferences and needs, we encountered some challenges that were unique to virtual interactions. For example, several participants experienced technical difficulties during the study and external distractions (e.g., answering a call), which briefly interrupted the flow of the activity. Similar limitations were identified in Cajamarca et al., remote co-design study with older adults [12]. Furthermore, participants might have experienced more fatigue related to using a screen for a long period of time, which could have made it challenging for them to concentrate. To address this, we prompted the participants to take a five-minute break as needed.

Additionally, recruitment for homebound older adults can be difficult. Therefore, we acknowledge that our study's sample size is smaller than other qualitative studies (e.g., interviews) and may not represent the perspectives of other homebound older adults and their caregivers. However, by involving older adults and caregivers as co-designers, we gathered valuable insight and engaged with them in much more detail than we would have through interviews. Finally, in addition to older adults’ family caregivers, primary care physicians, and mental health professionals are other important stakeholders in older adults’ care teams. Therefore, future work should further explore other stakeholders’ perspectives on how to best design VIPAs interactions to support older adults’ mental health interventions.

7 CONCLUSION

As the number of homebound older adults continues to rise in the U.S. along with their high rate of depression, supporting older adults’ mental health becomes critical. Our study worked with family caregivers and older adults to co-design a VIPA to deliver evidence-based mental health services. Interactions with VIPAs are primarily voice-based, which highlights the importance of designing engaging dialogues that would be appropriate for such interactions. While some anthropomorphic characteristics are preferred (e.g., empathy and humor) when older adults desire social and emotional support, older adult users and their caregivers generally reject an overly anthropomorphic agent for other mental health-related interactions. Furthermore, although text-based and voice-based conversational agents share many similarities and user experience principles, exploring the acceptability of delivering mental health interventions using VIPAs can improve accessibility for older adults when receiving mental health services, both in terms of access to care and mode of interaction (i.e., using voice instead of touch). Our study begins to explore the role VIPAs could play in the larger mental healthcare system, moving VIPAs to be collaborators instead of tools. Our work therefore contributes to the intersection of both research in VIPA-older adult interaction design and VIPAs for mental health intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health (P50MH119029) and we thank our participants for their participation.

REFERENCES

- Hojjat Abdollahi, Ali Mollahosseini, Josh T. Lane, and Mohammad H. Mahoor. 2017. A Pilot Study on Using an Intelligent Life-like Robot as a Companion for Elderly Individuals with Dementia and Depression. 2017 IEEE-RAS 17th International Conference on Humanoid Robotics (Humanoids), 541–546. https://doi.org/10.1109/HUMANOIDS.2017.8246925

- Claire K. Ankuda, Bruce Leff, Christine S. Ritchie, Albert L. Siu, and Katherine A. Ornstein. 2021. Association of the COVID-19 Pandemic With the Prevalence of Homebound Older Adults in the United States, 2011-2020. JAMA Internal Medicine 181 (12 2021), 1658. Issue 12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4456

- American Psychological Association. 2017. What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy?https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral

- Karen Bonilla and Aqueasha Martin-Hammond. 2020. Older adults’ perceptions of intelligent voice assistant privacy, transparency, and online privacy guidelines. Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2020). https://hdl.handle.net/1805/28306

- Judith Borghouts, Elizabeth V. Eikey, Cinthia De Leon, Stephen M. Schueller, Margaret Schneider, Nicole A. Stadnick, Kai Zheng, Lorraine Wilson, Damaris Caro, Dana B. Mukamel, and Dara H. Sorkin. 2022. Understanding the Role of Support in Digital Mental Health Programs with Older Adults: Users’ Perspective and Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Formative Research 6 (12 2022). Issue 12. https://doi.org/10.2196/43192

- Andrea Botero and Sampsa Hyysalo. 2013. Ageing together: Steps towards evolutionary co-design in everyday practices. CoDesign 9 (3 2013), 37–54. Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2012.760608

- Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2006), 77–101. Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Robin Brewer. 2017. Understanding and Developing Interactive Voice Response Systems to Support Online Engagement of Older Adults. Ph. D. Dissertation. Northwestern University.

- Robin Brewer, Casey Pierce, Pooja Upadhyay, and Leeseul Park. 2022. An Empirical Study of Older Adult's Voice Assistant Use for Health Information Seeking. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems 12 (6 2022). Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3484507

- Robin N. Brewer. 2022. "If Alexa knew the state I was in, it would cry": Older Adults’ Perspectives of Voice Assistants for Health. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491101.3519642

- Amanda Buddemeyer, Jennifer Nwogu, Jaemarie Solyst, Erin Walker, Tara Nkrumah, Amy Ogan, Leshell Hatley, and Angela Stewart. 2022. Unwritten Magic: Participatory Design of AI Dialogue to Empower Marginalized Voices. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1145/3524458.3547119

- Gabriela Cajamarca, Valeria Herskovic, Andrés Lucero, and Angeles Aldunate. 2022. A Co-Design Approach to Explore Health Data Representation for Older Adults in Chile and Ecuador. Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 1802–1817. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533558

- S J Duff Canning, L Leach, D Stuss, L Ngo, and S E Black. 2004. Diagnostic utility of abbreviated fluency measures in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia.Neurology 62 (2 2004), 556–62. Issue 4. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.62.4.556

- Rajdeep Chatterjee, Saptarshi Mazumdar, R. Simon Sherratt, Rohit Halder, Tanmoy Maitra, and Debasis Giri. 2021. Real-Time Speech Emotion Analysis for Smart Home Assistants. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 67 (2 2021), 68–76. Issue 1. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2021.3056421

- Minji Cho, Sang su Lee, and Kun-Pyo Lee. 2019. Once a Kind Friend is Now a Thing: Understanding How Conversational Agents at Home are Forgotten. Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 1557–1569. https://doi.org/10.1145/3322276.3322332

- Jane Chung, Michael Bleich, David C. Wheeler, Jodi M. Winship, Brooke McDowell, David Baker, and Pamela Parsons. 2021. Attitudes and Perceptions Toward Voice-Operated Smart Speakers Among Low-Income Senior Housing Residents: Comparison of Pre- and Post-Installation Surveys. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211005869

- Leigh Clark, Nadia Pantidi, Orla Cooney, Philip Doyle, Diego Garaialde, Justin Edwards, Brendan Spillane, Emer Gilmartin, Christine Murad, Cosmin Munteanu, Vincent Wade, and Benjamin R. Cowan. 2019. What makes a good conversation? Challenges in designing truly conversational agents. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300705

- Graeme W. Coleman, Lorna Gibson, Vicki L. Hanson, Ania Bobrowicz, and Alison McKay. 2010. Engaging the Disengaged: How Do We Design Technology for Digitally Excluded Older Adults?Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, 175–178. https://doi.org/10.1145/1858171.1858202

- Lorena Colombo-Ruano, Carlota Rodríguez-Silva, Verónica Violant-Holz, and Carina Soledad González-González. 2021. Technological acceptance of voice assistants in older adults: An online co-creation experience. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. https://doi.org/10.1145/3471391.3471432

- Cynthia F. Corbett, Elizabeth M. Combs, Pamela J. Wright, Otis L. Owens, Isabel Stringfellow, Thien Nguyen, and Catherine R. Van Son. 2021. Virtual home assistant use and perceptions of usefulness by older adults and support person dyads. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (2 2021), 1–13. Issue 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031113

- Samuel Rhys Cox and Wei Tsang Ooi. 2022. Does Chatbot Language Formality Affect Users’ Self-Disclosure’. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. https://doi.org/10.1145/3543829.3543831

- Andrea Cuadra, Jessica Bethune, Rony Krell, Alexa Lempel, Katrin Hänsel, Armin Shahrokni, Deborah Estrin, and Nicola Dell. 2023. Designing Voice-First Ambient Interfaces to Support Aging in Place. Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 2189–2205. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596104

- Sarah M Donelson, Christopher M Murtaugh, Penny Hollander Feldman, Kamal Hijjazi, Lori Bruno, Stephanna Zeppie, Shiela Kinatukara Neder, Eva Quint, Liping Huang, and Amy Clark. 2001. Clarifying the Definition of Homebound and Medical Necessity Using OASIS Data: Final Report. Technical Report. ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/clarifying-definition-homebound-medical-necessity-using-oasis-data-final-report

- Sandra W Duchin and Edward D Mysak. 1987. Disfluency and rate characteristics of young adult, middle-aged, and older males. Journal of communication disorders 20, 3 (1987), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9924(87)90022-0

- Tessa Eagle, Conrad Blau, Sophie Bales, Noopur Desai, Victor Li, and Steve Whittaker. 2022. "I don't know what you mean by ’I am anxious’": A New Method for Evaluating Conversational Agent Responses to Standardized Mental Health Inputs for Anxiety and Depression. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems 12 (6 2022). Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.1145/3488057

- Nicholas Epley, Adam Waytz, and John T. Cacioppo. 2007. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism.Psychological Review 114 (2007), 864–886. Issue 4. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.864

- Francesca C. Ezeokonkwo, Kathleen L. Sekula, and Laurie A. Theeke. 2021. Loneliness in homebound older adults: Integrative literature review. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 47 (8 2021), 13–20. Issue 8. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20210624-01

- Pedro Guillermo Feijóo-García, Mohan Zalake, Alexandre Gomes de Siqueira, Benjamin Lok, and Felix Hamza-Lup. 2021. Effects of Virtual Humans’ Gender and Spoken Accent on Users’ Perceptions of Expertise in Mental Wellness Conversations. Proceedings of the 21th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1145/3472306.3478367

- Hannah Gaffney, Warren Mansell, and Sara Tai. 2019. Conversational Agents in the Treatment of Mental Health Problems: Mixed-Method Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 6 (10 2019), e14166. Issue 10. https://doi.org/10.2196/14166

- Barbara Given, Paula R. Sherwood, and Charles W. Given. 2008. WHAT KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS DO CAREGIVERS NEED?Journal of Social Work Education 44 (9 2008), 115–123. Issue sup3. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2008.773247703

- Meghana Gudala, Mary Ellen Trail Ross, Sunitha Mogalla, Mandi Lyons, Padmavathy Ramaswamy, and Kirk Roberts. 2022. Benefits of, Barriers to, and Needs for an Artificial Intelligence–Powered Medication Information Voice Chatbot for Older Adults: Interview Study With Geriatrics Experts. JMIR Aging 5 (4 2022), e32169. Issue 2. https://doi.org/10.2196/32169

- J. L Haggerty. 2003. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 327 (11 2003), 1219–1221. Issue 7425. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219

- Margot Hanley and Shiri Azenkot. 2021. Understanding the Use of Voice Assistants by Older Adults. Technical Report.