Resistive Threads: Electronic Streetwear as Social Movement Material

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3661537

DIS '24: Designing Interactive Systems Conference, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark, July 2024

Informed by legacies of textile activism, we design Resistive Threads as a wearable probe to investigate potential roles and trajectories of electronic streetwear in US urban social movements. Resistive Threads is an interactive denim jacket that refashions the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project's (Dis)location Black Exodus print zine. The jacket plays audio stories, poetry, and music from embedded speakers when interactive patches sewn with conductive thread are tapped upon. Examining the artifact with 10 community organizers and partners, we find that augmented streetwear may take on the role of a housing organizing instrument or speculative garment. In turn, we discuss how we might learn from textile histories and solidarities to recognize—not rehearse—damage-centered research. We close with a reflection on what makes the electronic aspect of e-textiles meaningful to social movement practice and performance.

ACM Reference Format:

Brett A. Halperin, William Rhodes, Kai Leshne, Afroditi Psarra, and Daniela Rosner. 2024. Resistive Threads: Electronic Streetwear as Social Movement Material. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS '24), July 01--05, 2024, IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark. ACM, New York, NY, USA 17 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3643834.3661537

1 INTRODUCTION

Expanding rich histories of activism through fabric-making [2, 12, 24], from the AIDS Quilt [60] to Chilean arpilleras [2, 3], design scholars have long energized textile metaphors and matters as sites of social change. Whether investigating quilts as living digital archives [93] or jackets as wearable instruments [73, 82], scholars have used textiles to enliven new modes of computational practice and criticism. This range of work has drawn attention to bodily experience beyond heads, hands, and eyes [72]; enriched histories of innovation by expanding who counts as an innovator [71]; and helped make present the labor of production and maintenance underlying everyday tools [68]. Electronic textiles (e-textiles) scholarship oriented toward justice [100] has ventured beyond individual and dyadic encounters to consider collective memory and action [97, 99], shifting its questions into a communal register [78].

In this paper, we build on this collection of work to investigate the central question: what might woven and worn electronics bring to conversations on US urban social movements? Drawing on a multi-sited collaborative design process and immersion within the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP)—a housing justice collective with chapters primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and New York City—we develop Resistive Threads: an e-textile probe connecting urban street fashion with audio stories, poetry, and music about the city life and housing struggles of Leshne and community partners. Our inquiry expands the AEMP's (Dis)location Black Exodus zine, which chronicles histories of racial expulsion, exclusion, incarceration, and resistance among Black residents in the San Francisco Bay Area [84]. Shifting narrative and aesthetic elements of the zine into a wearable probe, we examine connections between anti-gentrification practices and streetwear [53].

Streetwear is associated with staple garments like graphic tees, hats, hoodies, sneakers, and jackets, as well as styles like denimwear, workwear, sportswear, skatewear, and other casual wear. Emerging with anti-consumerist, rebellious, and social justice origins, streetwear as a fashion genre has long put expression to oppression in sub/urban environments (without digital intervention for the most part). African-American designer Willi Smith is credited with coining the term “streetwear” to describe the sportswear label that he launched in 1976 in New York City [1, p.23]. Soon after that, designers Carl Jones and T.J. Walker started Cross Colours in Los Angeles in 1989 to reanimate the 1960s Black Power and civil rights movements [p.130, ibid]. More recently, however, streetwear has undergone massive cultural appropriation, dislocating from its origins amid corporatization. What was once about resisting normative formalwear, as well as expressing counter-cultural projects such as punk rock, Hip Hop, graffiti, and do-it-yourself (DIY) fashion has mutated into a billion dollar industry [ibid]. Corporations have effectively “gentrified” streetwear [53], extracting cultural cache from the periphery: Black, Brown, Indigenous, Jewish, queer, working class, and other counter-cultural visionaries.

Informed by these histories, we use the term Resistive Threads to describe our wearable probe in two senses: (1) as a reference to the social and political action associated with legacies of textiles resistance; and (2) as a reference to the opposition to a flow of electric current that is used to power a speaker. Exploring this dual meaning, we engage resistive streetwear as a site for examining self-reflection and community care associated with fabric. Rather than work toward a product or test for viability, our project contemplates questions of body-based material technology [79] to reflect on different healing capacities in urban space. Notably, the jacket could be analyzed in connection with histories of streetwear, their design elements, and wider themes of fashion within consumption studies and material culture studies; here we instead orient our analysis around textile activism, and consider what might be learned for scholars working with e-textiles and digital storytelling around movement building.

Across this work, we make three core contributions to design research on e-textiles and design for social movement organizing. For one, we bring urban studies considerations of race, place, and space to e-textiles discourse, analyzing tensions around speculation and instrumentalization as two different design trajectories for body-based technology within this context. Second, we examine how e-textiles practice, performance, and inquiry might help mend what Eve Tuck describes as “damage-centered research” [105] about communities of color by interweaving and processing multi-dimensional stories of struggle with creative expression, joy, and healing. Lastly, we present a case study in remediation of a print zine and analog textiles into a wearable, complicating what it means to “refashion” versus “rival” legacy media with emerging forms of digital augmentation [9]. We find that remediation and electrification within this context presents a dynamic medium with new possibilities for reembodied experiences and social performances.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 (E-)Textiles for Storytelling and Justice

Textiles have long been a contested technological craft. Woven, knit, crocheted, embroidered, sewn, fabric artifacts reflect an intricate process of production and development tied to skillful handwork, inventive instrumentation, and industrial manufacturing. But they also reflect longstanding histories of patriarchal stratification and control that textile artists have long sought to overcome and rework [15]. As art historian Rozsika Parker [94] observes, “to know the history of embroidery is to know the history of women” (ix). Her comment refers to the century-long demotion of threadwork to the realm of feminized domesticity and the accordingly devalued domain of decorative arts. Shifting from the home to the factory, this differential treatment lives on in the computing industry which, like the garment industry, relies on a racialized and feminized workforce, often compelled by colonial legacies of manufacturing [71].

In response, artisans have actively reclaimed, undone, and remade textile tools and materials as seeds of social movement-building. From the burlap-backed tapestries of the Chilean arpilleristas [2, 3], to the encoded escape routes for enslaved Black Americans of the contested Freedom Quilt [70], to the Changi Prison Quilts that prisoners crafted in Japan during World War II [24], textiles have long served as sites for protest, activism, and political organizing, raising provocative questions for social and ethical possibility. In Julia Bryan-Wilson words: “What does it mean to imagine the sewing needle as a dangerous tool and to envision female collective textile making as a process that might upend conventions, threaten state structures, or wreak political havoc?” [12]. Our work takes up this question and its attendant concern for minoritarian collectivity within the context of US urban social movements with an emphasis on housing justice. In particular, we build upon the work of Tania Pérez-Bustos, Laura Juliana Cortés, and colleagues who work with e-textiles as a relational method of inquiry to support oral storytelling and healing in the aftermath of Colombian warfare [19, 21, 74, 75, 78] (see Remendar lo Nuevo [76, 77]). We draw inspiration from these projects while working on the (Dis)location Black Exodus zine refashioned into a streetwear staple: the denim jacket.

Denim jackets have long been sites of creative resistance in urban contexts [83]. In 1998, Rhemi Post, Maggie Orth, and colleagues designed a denim jacket as a wearable instrument to play music via an embroidered keypad built with resistive yarns, sensors, speakers, a MIDI synthesizer, and more [73, 82]. Soon thereafter in 2000, Flavia Sparacino and colleagues designed “wearable cinema/wearable city” as a denim jacket, consisting of an embedded central processing unit, head-mounted display, and other parts to simulate immersion in a city while watching a movie from inside the set [98]. These works have laid fruitful ground for other e-textiles work on urban justice and expressive storytelling.

A growing body of e-textiles work has materialized tangible narratives as cultural artifacts, in some cases through physical embodiment [17] and others through screen mediation. Some works have looked to augment textiles craft with storytelling mechanisms that smartphones offer such as capturing traces of a creative knitting process [91, 92], and prompting inspiration to thread stories in the form of embroidered text messages [61]. Of particular relevance to our genre is Brett Halperin's interactive storytelling streetwear designed to amplify counter-cultural voices through embroidered QR codes that, when scanned with smartphone cameras, link to motion graphics and music in AR/VR/3D environments; his work calls for reorienting storytelling power amid mass cultural appropriation and co-optation of streetwear [45]. While his work and others suggest how screen mediation (e.g., smartphones or body-based monitors) might augment textiles, Laura Devendorf and colleagues importantly note the undesirability of wearing screens [26].

Prior work suggests that embedding physical computing into textiles without screen interference might render storytelling in more intimate and uninterrupted ways. Afroditi Psarra, Daniela Rosner, and colleagues, for instance, have shown how intimate material encounters [8] can unravel the sensing of textures and politics [86], as well as the (re/un)making of memories [93] and reorientation of bodies through techno-poetic engagements with fabric [85, 89]. Along with embodied making, Alexandra Riggs and colleagues have fashioned interactive wearable buttons that elevate queer histories of activism [88]. While these works illuminate embodied crafting and tangible narrative tactics [90], they only begin to scratch the surface of how e-textiles might be oriented toward collective memory and action [50].

Integrating the two traditions of textile-making and community-building presents opportunities for crafting alternative computational logics [80] across boundaries [81, 100]. Prior work has shown how e-textiles might address social problems in material, metaphorical, and practical ways. These works include speculating spiritual technologies “in the interests of Blackness” [16]; situating meanings of reconciliation [19]; refiguring ways of knowing the body through music [54]; materializing memoirs of struggle [25]; crafting ecologies of care [39] and resistance [40]. Angelika Strohmayer argues that the plurality of community voices crafted into a digitally-augmented Partnership Quilt conveys the import of telling multiple stories via a single text [99], which has become increasingly vital as computing complicates how housing struggles are narrated [46, 47]. Drawing inspiration from these works, we use the denim jacket as a site for probing relationships to the body, digitally mediated storytelling, and US urban social movements for housing justice.

2.2 Community-Based Design and Urban Media Technology

Much design research has investigated urban media technology through modes of community-engagement, collective organizing, and speculative futuring [10, 13, 14, 33, 55, 56]. From designing data visualization and geographic information systems (GIS) [31, 32, 44, 48, 63, 95] to digitally supporting collective storytelling [28, 46, 67, 107], this body of work has grappled with the possibilities and pitfalls of community-based research. In such contexts, Eve Tuck calls for suspending damage-centered research, which is “research that intends to document peoples’ pain and brokenness” [105] with perhaps earnest but misguided intentions. Tuck not only calls for suspending deficit frames and narratives of “marginalized” groups as depleted without agency, but also the continued portrayals of communities of color as damaged and defeated as these approaches might do more harm than good over the long run [ibid].

Designing in community contexts such as displacement thus calls for critically considering who gets to future, and what role technology might play in futuring, but not forcing a “techno-fix” of inequities that Black communities in particular face [22, 51, 104]. The rise of “smart cities” [34, 52, 106] along with the automation of gentrification and deployment of algorithmic technologies to surveil and incriminate low-income tenants [59, 66] has made it ever more crucial to design what Erin McElroy describes in relation to the AEMP's work as “technologies of the otherwise that produce antiracist imaginaries and materialities” [65]. The AEMP has reflected upon how designing technologies of the otherwise means rejecting status quo design methods [58] and values entangled with Silicon Valley techno-capitalism that have fueled displacement [48]; it also entails probing the raciality of automation and the potential harms of scaling technology in organizing contexts that depend upon situated, localized (non-universalized) action and knowledge [35, 46]. From these works, we learn about how community-based technology can augment, rather than automate, bodies with space and place-based artifacts that are concerned not with scaling, but materializing alternative imaginaries.

With approaches like social justice-oriented interaction design [29, 36], prefigurative design [4], and design justice [20], prior work offers rich insights on how design might amplify the work of community organizations and grassroots movements. In the context of urban housing justice, Mariam Asad and Chris Le Dantec telegraph the importance of designing for existing activist practices, rather than installing new ones with technology [5]. This insight dovetails with what Daniela Rosner theorizes as “extensions”—or modes of extending community-based scholarship into meaningful forms of cultural artifacts (e.g., zines) that belong to communities, while orienting design toward activism [38, 90]. With respect to design activism, digital storytelling has played an integral role in “challenging false narratives and exposing realities” [67]. However, as Christina Harrington and colleagues have found, there are significant “barriers to obtaining narratives” about precarities in urban communities of color due to stigmas and fears of landlord retaliation [51]. It is thus crucial for grassroots movements to document the stories in some fashion. As David Philip Green and colleagues have shown, grassroots digital production systems produce stories that are more “intimate” and “realistic” than those of professional production systems [43]. Design scholars have also shown that documenting community histories can archive counter-narratives about urban inequities that might otherwise not be recorded [33, 63], as well as amplify local voices to influence change [37]. To address challenges that can arise in such processes, Sucheta Ghoshal and colleagues envision a grassroots technology practice that involves critically analyzing structural exclusion [41], while examining “artifacts and practices for the politics that they embody” [42]. As these works call for understanding what cultural artifacts embody, mobilizing grassroots stories, and extending community organizing practices, they have only begun to reveal what embodied technology (namely e-textiles) might bring to urban contexts.

2.3 Remediation

This turn to the embodied technology of e-textiles considers the means by which urban environmental movements might refashion or remediate toxic conditions and systems, a process that we might call remediation. In design research, remediation has variously referred to the repair of environmental degradation [87] and hegemonic systems (e.g., through community-based translation work [101]), as well as (via [9]) the reworking of older media into newer forms of media such as e-textiles [96].

In reformatting the AEMP's (Dis)location Black Exodus print zine [84] into a wearable digital media artifact, we draw upon Erin McElroy's discussion of remediation in an environmental sense with respect to the zine, as well as Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin's conceptualization of remediation in a critical cultural sense as a “formal logic by which new media refashion prior media forms” [p.273][9]. In threading these perspectives, we assess what it means to refashion both a print zine and analog textiles into electronic streetwear by comparing the forms of media reception. While calling for alternative imaginaries of technology that are anti-racist, McElroy writes about a neighborhood foregrounded in the zine: “Today, the [Bayview-Hunters Point] neighborhood contains some of the city's highest toxin rates, due to its former shipyard and failed remediation” [65]. McElroy further describes how activists such as Marie Harrison (whose story is featured in the zine and our wearable) organized against the unremediated toxins before passing away from the health effects of environmental racism [65, 84]. In drawing these connections between remediation as environmental and cultural analytics, we set out to investigate the possibilities around refashioning legacy media in both of these senses.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Through Design (RtD)

We draw from an integrative approach to design inquiry that includes community-based collaborative design of a wearable probe (interviews connected with Resistive Threads). In the spirit of RtD, we use our design process to produce knowledge—neither to inform product development and manufacturing [108] nor to “solve” systemic inequities with a techno-fix [69]. Through the making and probing of electronic streetwear, we endeavor to understand its potential roles and material trajectories in US urban social movements that are already engaged in cultural production projects.

3.1.1 Immersion Within the AEMP. Our work involved immersion within the AEMP, a collaborative process of turning the zine into a wearable, and one-on-one interviews with 10 community partners alongside a discussion and demonstration of Resistive Threads. The jacket production began with AEMP's (Dis)location Black Exodus zine, which traces long histories of racial expulsion, exclusion, inequity, and incarceration, as well as resistances among Black residents in the San Francisco Bay Area [84]. Halperin, Rhodes, Leshne, and Rosner had previously worked with the AEMP on various projects over the years, with Halperin first joining the New York City chapter in 2020. In 2022, the collective asked Halperin to design a way to extend and foster experiential moments of engagement with (Dis)location Black Exodus content. A subgroup of AEMP volunteers and zine makers including Halperin noticed connections between racialized dispossession and street style [53], prompting the idea to expand and reformat the zine as a lyrical artifact of narrative streetwear. We, as a team of Black and white co-authors (including AEMP members and a creator of the zine), worked with additional Black AEMP members and creators of the zine. We also worked with multi-racial partners at other sites of community partnership. We thus formed a multi-city coalition including Los Angeles, New York City, Seattle, St. Louis, and the San Francisco Bay Area. We interviewed seven partners affiliated with the AEMP (and other organizations), including four who worked on the zine. Additionally, we interviewed three partners who are community organizers at other organizations. Our interlocutors ranged from ages 28 to 66; six identify as Black, four as disabled, and three as having previously lived unhoused. We note these identities because of their particular relevance to urban space, place, and race.

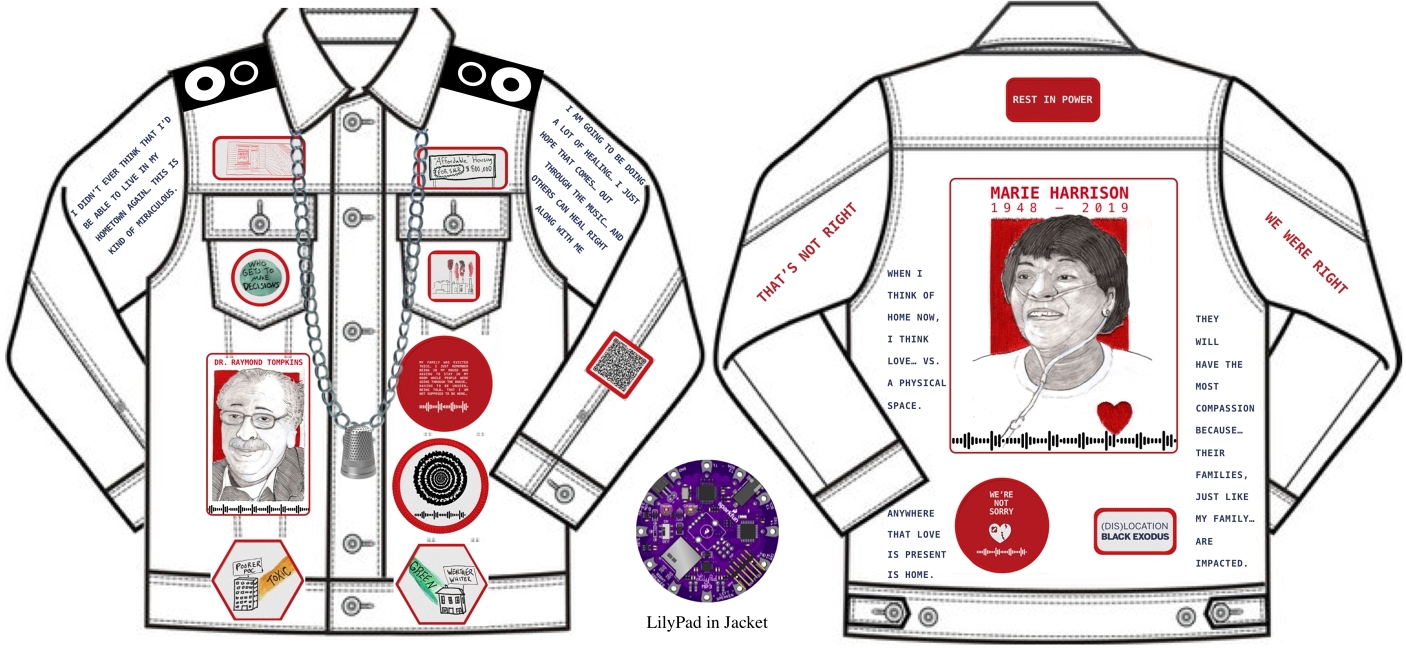

3.1.2 Visual Mockup and Video Prototype. To begin, we made a visual mockup (Fig. 2) and video prototype of the jacket to probe with 10 community partners. Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval of the study, we recruited participants whom we had preexisting relationships with through the AEMP and other community organizations. We held one-on-one remote 60+ minute interviews via Zoom with each interlocutor who received a $100 gift card. In the first half of the interview, we asked about their prior experiences working on the zine or organizing their communities in particularly embodied and creative ways, as well as how they thought about the role of garments in social movements. In the second half, we asked interlocutors to critique the visual mockup and video prototype: a three-minute compilation of frames to demonstrate the concept with audio. Some interlocutors interviewed at later stages also critiqued the physical jacket. The design process was structured such that the co-authors assembled the jacket, while interlocutors provided feedback throughout the process given their time, location, and capacity constraints. We iterated on the design and materialized the physical jacket according to feedback. For example, one interlocutor suggested including his slam poetry about living unhoused, so we adapted the design. To protect privacy, we reflexively assign each interlocutor a pseudonym [57].

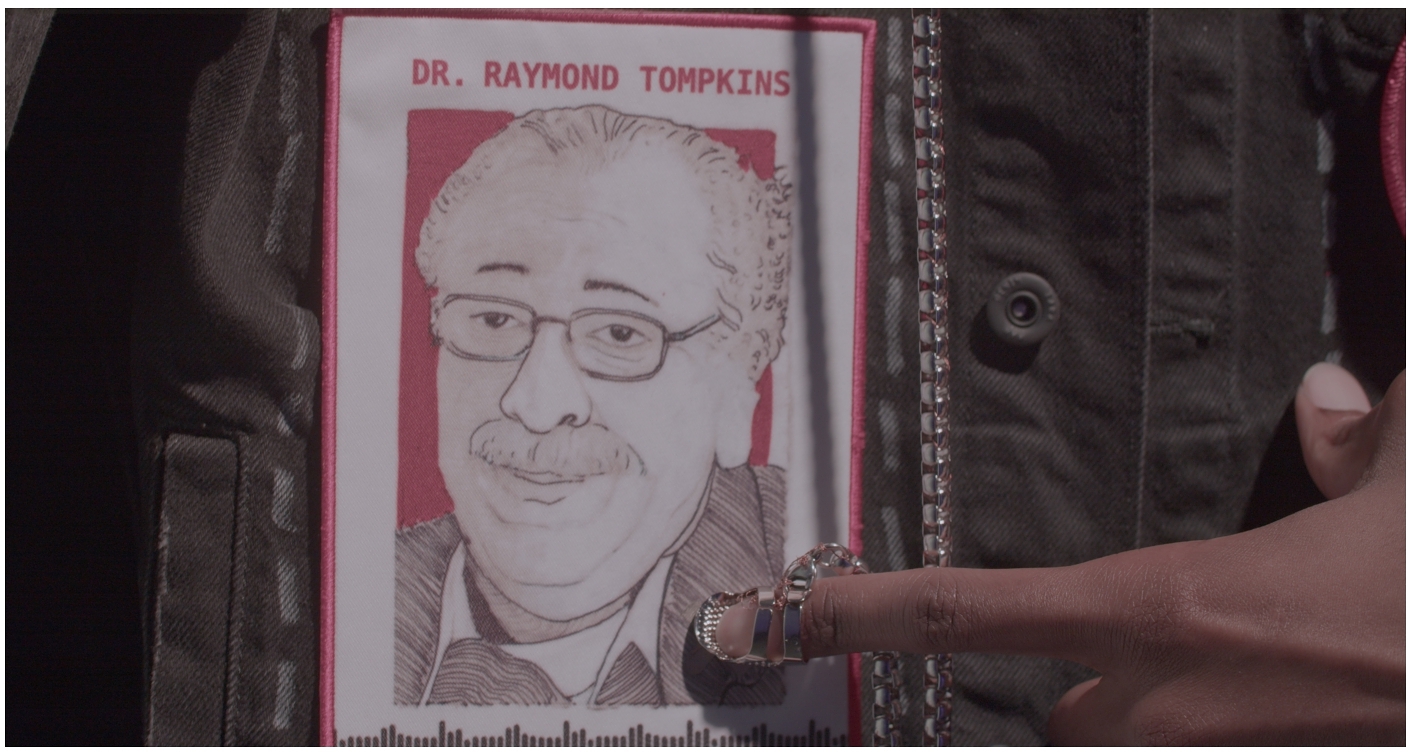

3.1.3 Physical Prototype. Based on the iterative feedback, we physically assembled the jacket. In working on the original zine, Rhodes, a San Francisco-based textile artist, illustrated portraits of people whose stories are featured. He incorporated red threads as symbols of their sacrifice and blood, representing a bond that all humans share. He started the portrait by selecting a thick cotton paper and drawing out the image with a 6B graphite pencil. Then he added hand-sewn sections to the portrait using a nylon thread. The thread is not only symbolic, but also metaphorical in how it threads the distinct yet related Black histories together. In turning the zine into a wearable, we thus expand upon the red thread motif, adding conductive thread to materialize the electronic denim jacket with screen prints of the portraits and other zine illustrations by Robin Bean Crane. Going into the project, we planned to exhibit the jacket in different cities, including in San Francisco at an upcoming AEMP (Dis)location Black Exodus community event. Another potential idea was for Leshne, whose music is embedded within it, to wear it while performing on tour. Our conversations with interlocutors raised many other ideas around how and where the jacket might exist, which we elaborate on below.

The denim jacket is like a wearable rendition of the zine. While it has accessibility limitations given its experimental nature, it offers different entry points of interaction through tactile, visual, and auditory channels. Interactive patches are sewn with conductive thread to play stories, poetry, and music aloud via embedded speakers. Around the denim jacket is a metal chain necklace with a thimble as a pendant for people to put their fingers inside and thus trigger audio files stored in a LilyPad MP3 microcontroller. The chain is long enough to reach all patches, including ones on the back of the jacket. The microcontroller holds five audio tracks, which include slam poetry, music, and oral histories remixed with city sounds and instrumental music. In light of the dislocation theme, the jacket itself is artfully dislocated. The music and poetry are not part of the original zine, but rather added elements that expand beyond the San Francisco Bay Area. These elements were added in our process of building a multi-city coalition, where we have community partnership sites to thread connections across social geographies.

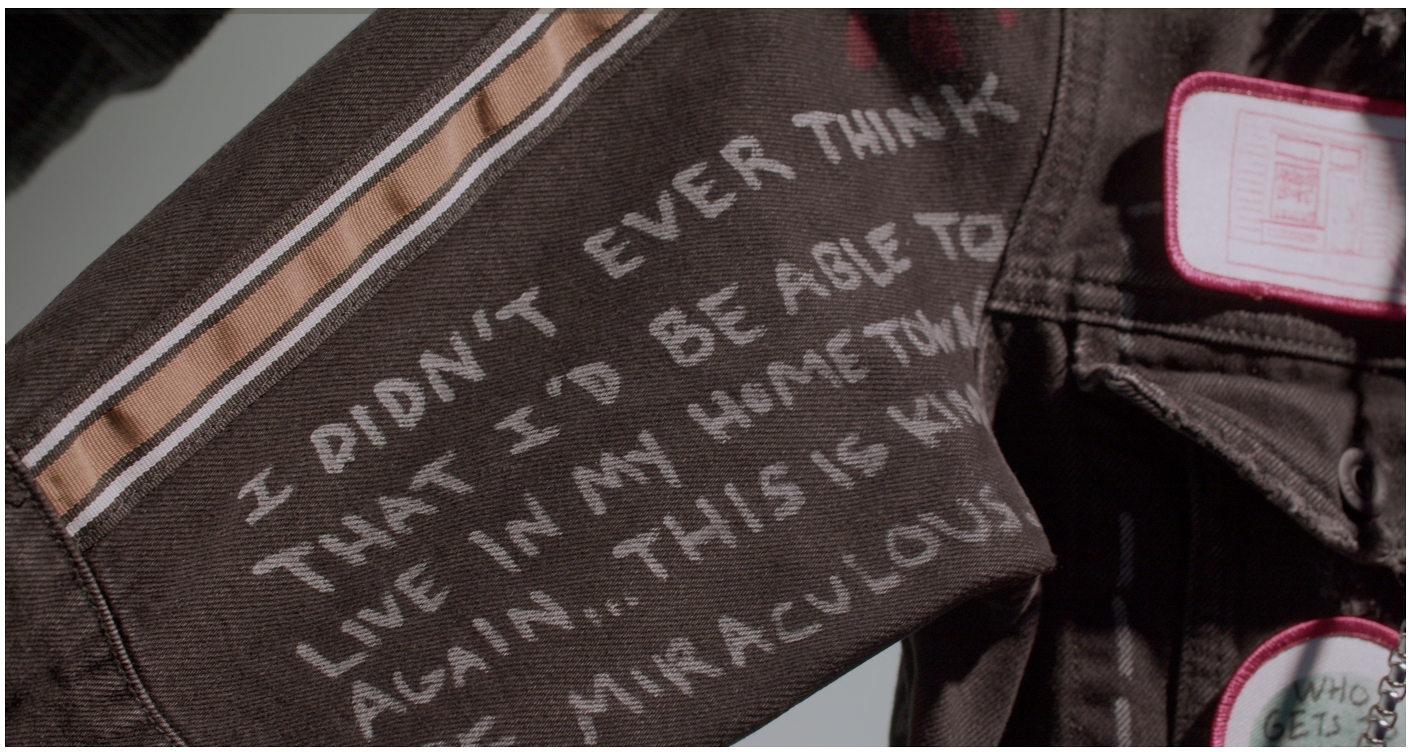

The jacket embodies patches selected for aesthetic and evocative characteristics, as well as spatial place-based groundings, which build upon other (auto)biographical wearable designs [27, 102]. One featured song, Infinite by Leshne (CHANNELS) from his album Cold Coast, tells a personal narrative about communal upheaval and lack of affordable housing in the San Francisco Bay Area. After experiencing eviction, Leshne thought that he would never be able to live in his hometown again (as quoted on the jacket). Another song, We're Not Sorry by Gabrial Thompson, a music artist based in St. Louis, is a poetic response to systemic racism that suggests a collective plight across urban landscapes and borders. Another audio file is the slam poetry of one interlocutor who expresses his experiences of living without housing in New York City. The fourth and fifth audio files are oral histories of Bay Area activists Raymond Tompkins and Marie Harrison who narrate their experiences of redevelopment and climate injustices. Their stories are written in the zine, but their spoken narrations, which the AEMP separately produced, exist outside of it. We screen-printed their portraits from the zine to create the interactive patches, which play their corresponding oral histories through the speakers when tapped upon. The auditory feedback thus emerges through the patches, becoming 3D in effect with an embodied and spatial presence.

3.2 Analysis

We took an analytical approach inspired by André Brock's critical technocultural discourse analysis (CTDA) [11] and Adele Clarke's situational analysis [18]. Viewing our interlocutors not as “users” but instead as co-theorizers, we conducted a multimodal analysis to foreground culturally and socially contingent interpretations of electronic streetwear. This involved applying critical cultural frameworks to both our analysis of the artifact (Resistive Threads) and the discourse surrounding it (interview transcripts) [11]. To arrive at themes that follow, we used techniques from situational analysis for mapping the visual and material discourse surrounding the artifact, as well as identifying concerns for social organizing, speculation, and positioning. Heeding to Clarke's analysis of remediation as a cultural analytic (via Bolter and Grusin [9]), we paid attention to how refashioning older media can reinscribe conventional forms of oppression (e.g., racism, ableism, etc.) that are “gussied up” in new forms of representation [18, pg.276]. Altogether, this multimodal approach allowed us to analyze how social movement organizing is embedded with woven, aesthetic, and electronic signifying practices, as well as what pitfalls and potentials e-textiles might materialize within this context of US urban social movements.

4 FINDINGS

Below, we analyze how our interlocutors perceived Resistive Threads as a community organizing instrument on the one hand and a speculative garment on the other. In this process, we explore possible uses, expansive interactions, and soulful connections surrounding real and imagined potentials of electronic streetwear that the artifact evoked. Finally, we explore positionality questions around the electronic streetwear artifact vis-à-vis urban space, place, and race.

4.1 Electronic Streetwear as an Organizing Instrument

Some interlocutors perceived electronic streetwear as a community organizing instrument. In practical terms, they spoke to how Resistive Threads might amplify existing practices such as exhibiting community art, advocating, and rallying constituents. They also conveyed its potential as a movement-building mechanism to shift narratives, advance sociocultural change, and support disabled organizers in carrying around information.

As AEMP members, Ariel, Rose, and Ali, spoke to how the zine was born out of a larger vision for organizing around the content through experiential moments of public engagement (e.g., online, in a classroom, or at an exhibition). Given the low-resources of the collective, however, they shared that many of their visions for digital expansion in particular were never fully realized. In turn, they saw the jacket as a way to materialize some of their practical visions for extending the zine (materially, spatially, and conceptually). Rose spoke to how she saw the conductive thread of the jacket expanding upon the collages and thread motif that run throughout the zine. She said: “As I understood [Resisitve Threads], it's something about the thread here that's allowing for these stories to be played. So I think that's such great building upon that theme... and the patchwork collage effect that is happening on the jacket.” Rose is referring to the central role of thread in both the zine and the jacket. For most e-textiles garments, including this jacket, the material relies on the fact that a thread holding fabric parts together also works as a wire carrying electricity. With her comment, Rose connects the thread metaphor running across the zine and the thread material in electronic streetwear. Rose is getting at how the jacket uses thread (metaphor and material) to expand existing organizing practices by documenting and sharing Black residents’ urban experiences, rather than introducing new practices altogether. She also mentioned how she had hoped for future iterations of the (Dis)location Black Exodus series to go beyond San Francisco. She appreciated how the jacket incorporated the voices of Black artists in other cities. Practically, our interlocutors perceived electronic streetwear as extending the AEMP's existing work and unrealized visions to animate the content as part of its ongoing organizing objectives.

Our interlocutors also had different ideas around how electronic streetwear might engage and expand public involvement in social movements. Jodi, a disabled organizer in Seattle who has lived without housing, described how she imagined wearing it to draw attention and raise awareness among everyday people. She said:

I organize just by talking... and other people would be coming straight up to me going: ‘Oh, my gosh! Can I read your jacket?’ And I'd be like ‘Yeah, actually, it's interactive. What do you want to learn?’... I'd wear it everywhere. I'd wear this to go get gas... to Costco to get my medication... to the hospital to my transfusions... I'd wear it everywhere because that's the type of organizing I do... I'm constantly engaging the randoms... because a lot of them have no idea what is going on... People are going to be hearing it, and that's going to grab their attention and then they're going to start asking the questions and that's the bigger picture... I think it can really get a lot more people maybe involved... learning stuff and just understanding and changing the narrative because that's what the most important thing is...

Jodi saw the jacket as an opportunity to engage the people (“randoms”) whom she encounters on her daily excursions, whether at the hospital or grocery store. While this substantiates prior work on how social wearables can attract the attention of strangers (e.g., [23, 30]), in this context, the spectacle may also facilitate impromptu organizing. While Jodi focused on strangers, Rita imagined the jacket supporting her constituents in need. As a founder of a grassroots tenant rights organization in St. Louis, Rita emphasized the importance of connecting the jacket to material impact for tenants. She contemplated how audiences might meaningfully benefit from the jacket by learning about their rights in the process of interacting with it. She made this point particularly clearly when she said that if the jacket intends to foster joy through music, then that means it has to “take the pain away.” For her, healing involves tangible collective action, beyond the gesture of touching a patch and listening to a song or story. Thus, Rita suggested that the jacket ought to exist in a social setting like a teach-in, where tenants learn to take specific steps to improve their situations through either direct engagement with the patches or mentorship and programming alongside it.

Interlocutors also reflected on how electronic streetwear might expand existing advocacy practices that focus on overturning false and harmful narratives, while celebrating new and liberatory ones as well. Rose and Rachel both spoke to how organizers often wear graphic tees with the faces of loved ones who have experienced injustices to show love and support for them. As Rachel mentioned, the graphic tees represent certain values in durable material that can be worn and thus mobilized in different places and spaces over time. In turn, they both saw the electronic jacket as amplifying this practice by making graphics more expressive and audible. As Matthew explained, fashion presents fruitful grounds for grassroots movement-building by way of cultural production. He said: “The last ten years of my homelessness, I've been involved with street poetry, clothes, fashion. Grassroots is amazing. Pop culture don't got nothing on grassroots because it comes from the street.” Matthew saw opportunity for electronic streetwear to enact cultural change from the ground up via everyday interactions on the street. Meanwhile, Richard shared a story about a community-based initiative called the Laundromat Project, which worked with the Housing is a Human Right project to play oral histories about housing in a laundromat to foster collective listening in a space, where people were united around clothing. In witnessing people at the laundromat, Richard said: “They went from staring at their clothes in the machine going around in circles to their ears pinned to these speakers in corners of the room.” In explaining how the stories “mesmerized” people, he said that he observed that listening to the stories made more people become willing to share their own stories that counter dominant narratives. He thus envisioned electronic streetwear having a similar effect in terms of captivating attention, destigmatizing experiences, and reshaping culture: “Culture, I understand, is a big part of this... It attracts the younger audience, which we need... So many university students in the city of New York are either homeless or at risk of homelessness, but they've been shamed into not sharing their stories.” Thus, several interlocutors viewed electronic streetwear as holding the practical potential to embolden grassroots activities.

Additionally, our interlocutors described how they imagined canvassers and advocates, including themselves, wearing electronic streetwear while attending community events, rallying, knocking on doors, and more. For instance, Jodi described how she saw it augmenting her advocacy work by not only starting conversations, but also carrying information around. In imagining wearing it to rallies, she said: “[It seems] easy for those of us, especially with disabilities, to be able to use because... sometimes my arms don't work at all.” Here, Jodi is envisioning the wearable nature of the jacket and its built-in speakers providing an accessible way for her to amplify stories at rallies instead of carrying equipment (e.g., a megaphone or speakers). She foresaw the latent potential for it to support disabled organizers in particular.

Lastly, Rachel described how she envisioned electronic streetwear facilitating physical interaction that fosters a communal sense of togetherness. In envisioning how the jacket might be used at a community event or rally, she said:

I think it's really moving to be able to generate audio like that without picking up your cell phone and having to play a video and share it that way... Instead of having everyone look at their own little devices and get their own meaning from things, I think it helps in the shared meaning and the shared experience... that would allow people to still be present... One person could xplay this and everybody could link arms [in a circle]... and... be in collective action without having to be distracted and defer away from that collectiveness to hear this story.

What Rachel is getting at is how personal devices with small screens engender a sense of individualism that runs counter to collective movement-building and interrupts social presence. She interpreted the jacket as a media player that can radiate outward onto a group since it does not confine an individual to looking down and inward at a screen. Even if only one person wears the jacket, it still allows for that person to be physically present and project the audio outward in shared space. Rachel thus saw potential for the screenless embodied technology to tangibly build community.

4.2 Electronic Streetwear as a Speculative Garment

In this section, we probe the augmented denim jacket as a speculative garment, inviting reflections on wider notions of bodily expression, namely electronic streetwear, and associated imaginaries. By imaginaries we refer to constructions of particular understandings of the world, which involve concerns for what bodies desire but may never attain [6, 7, 62, 64].

4.2.1 Reembodied Reception. Our interlocutors imagined what it might be like to wear the jacket, and what it might open up as a reembodied mode of reception holding the possibility to deepen bodily connections with the woven storytellers, as well as with one's inner self and other people who encounter it being worn.

As a participatory artist, designer, and researcher from San Francisco who worked on the zine, Ariel spoke to how the AEMP has long contemplated how it can “support both deep and intentional listening” to oral histories, while also questioning what might become possible with different modalities. In thinking about listening through the jacket versus other apparatuses (e.g., headphones or screens), Ariel explained:

I just would imagine that the people's voices would be more deeply felt, as opposed to some of the more disembodied ways of listening... Whereas, this way of listening, where you're physically connected to the audio in some way... I would imagine you could feel the vibrations of the audio.

With this vision for enwrapping wearers in sonic waves, Ariel imagined tactile and audible reception grounded in bodily sensations that electrify and amplify connections with the speakers (both the storytellers who speak and the electroacoustic transducers sewn onto the shoulders). In this way, she envisioned the jacket fostering a sense of listening that travels not only through ears and eyes, but also arms, torsos, and other body parts to enhance connectedness.

With a shared outlook, Rose, a geography scholar from San Francisco who worked on the zine, described how she foresaw the wearable material extending and deepening connections with the featured storytellers, as well as with one's inner self and others who encounter it being worn—or what Marvin, a San Francisco-based artist who also worked on the zine, described as “the potentiality of the interactions it provides.” Having experienced eviction while growing up in public housing in the San Francisco Bay Area, Rose first spoke to how she imagined the jacket helping to preserve personal memories: “There is an incredible amount of loss here when you're talking about displacement and how do people hold onto the material things and memories... Clothing is such a clever way to think about carrying on those memories. Sometimes you can't reclaim those places.” Rose perceived the jacket as a fitting extension of the zine because of how, in her view, it is a “natural complement” to other aspects of Black culture that she has engaged in (e.g., making t-shirts to honor people who pass away and airbrushing family members onto garments at graduation to signify “carrying them with you”). In bringing the jacket full of memories across places and spaces, she further imagined it fostering comfort amid the discomfort of displacement, while opening up opportunities to socialize these issues with other people. She said: “There's something very comforting about having something on, and to be able to interact with it, have other people ask you about it, and what that opens up.” Here, Rose imagines the act of wearing the jacket as a social performance that generates meaningful conversations and connections. With this vision, Rose conveyed how the body might carry, store, and share memories through the jacket as a way of holding onto parts of what gets lost in the communal upheaval.

Similarly envisioning the jacket as a mode of inhabiting and traversing urban space, Richard and Matthew compared the electronic jacket to other forms of media reception. Richard, a long-time activist and educator part of the AEMP NYC chapter who had lived unhoused for three years, spoke to how he imagined listening and walking around with the ”stories just radiating out” such that it sparks conversations. He added: “I could just imagine sitting around like 24th street in the Mission District just tapping my jacket to hear a different story.” In visualizing himself moving through the city with the jacket on and evoking his sense of touch, he communicated a reembodied mode of engagement. Likewise, Matthew, an artist part of the AEMP NYC chapter who had lived unhoused for 10 years, characterized the artifact as “singing clothes.” He imagined the jacket offering a personalized mode of listening, inhabiting, and traversing cities that “takes the pressure off you walking around with your phone or... with something always in your ear.” In speaking to how wearers can listen to the audio tracks without having to plug into phones or hook wires up to their eardrums, he conveyed how it might facilitate a reembodied experience of the music. Together, Matthew and Richard articulated visions for the jacket to activate bodily sensations while moving through urban spaces and places.

4.2.2 Soulful Connections. Some interlocutors speculated about how the soul comes into play—how the jacket threads ancestral stories and soulful music. Interlocutors first described how they understand the soul in various ways, including as a spiritual phenomenon that lives on beyond the human lifespan (e.g., as in the deceased souls who shared their stories in the zine), as well as one that connects the body to music on a deep level (e.g., in dancing to soul music). Some also described perceiving the soul as a source of benevolence and hope. Matthew, for instance, attributed surviving a decade of houselessness to becoming “at one” with his soul, which for him meant confiding in a higher power that inspired much of his poetry that is embedded within the jacket. Marvin also underscored the jacket's potential to hold “a body and a soul in there.” Speaking to its content, he envisioned a person “bringing it to life.” He then compared the jacket to other forms of media like film and the print zine that he had worked on:

When we hear audio things, there's a certain just artificiality to it... and even when you see a film, there's still just that barrier of the artificial aspect of it. It's on the screen. It's not in real life. And having a real person in this [jacket]... it goes from this [print zine], to a body, to being embodied. It has movement. It has the energy of life, transporting it through. Somebody's walking around with this.

Marvin is not saying that the print zine and other forms of media lack vitality, but rather how he foresees wearables as enabling someone to enliven the content beyond the artificial barriers of materials. This also gets at a point that Rose made about how the print zine “flattened” the oral histories and how the jacket might help “bring back” people's voices. In immersing a human body and soul inside of a wearable, they imagine the jacket animating particular messages and fostering soulful connections.

Along these lines, Ariel speculated about how deceased souls featured in the jacket might also play meaningful roles, as they did for her in making the zine. She explained:

There's always some soulful element of being in conversation with people who are no longer alive. A lot of the [zine] was remembering or calling in the names of people who no longer are here, or who weren't invited or asked to contribute their histories. And there was some sort of soulful element of creating space for those stories to be told.

Ariel is observing a present quality to the non-present (or absent) lives re-enlivened through stories of housing justice as told by deceased souls. The patch on the back of the jacket is a screen-printed portrait of Marie Harrison, a San Francisco-based activist who got terminally ill from toxic environmental conditions. In illustrating this portrait for the zine, Rhodes sought to honor Harrison's service by symbolizing her sacrifice and blood—a bond that all human's share—with red thread. For Rhodes, the act of sewing connects him with his ancestors. Similarly connecting on a “soul level” with the histories, Ariel speculated not only about the soul in this regard, but also in the healing power of music. She further reflected on how the jacket patched together Leshne's story of eviction and song about feeling infinite such that it did not only define him by his struggle. She said: “I can speculate that his music is a way for him to heal or for him to feel a vehicle of resilience amongst the difficult things he's navigating... It's nice for there to be stuff woven in that isn't just offering that perspective.” Through heartfelt listening and commemorating, she foresaw potential for electronic streetwear as “a vehicle for deeper embodiment, or soulful connections to the stories.”

4.2.3 Expansive Interactions. In imagining future possibilities of electronic streetwear, our interlocutors envisioned the wearable beyond its current form and functions. They shared ideas around how to make it more inventive, inclusive, interactive, and engaging. For one, Rose spoke to how she hoped for all kinds of bodies to find comfort in it. She said: “I like the idea of you put on a jacket, and you feel warm and comforted... How could you make that comforting for different people's ages, body types, abilities?” She thus desired for electronic streetwear to create comfort across bodies. Similarly, Rita, a long-time tenant activist in St. Louis, also dreamed of electronic streetwear in the form of more innovative garments like a “sweatshirt-dress” that she had recently purchased and excitedly retrieved to demonstrate. These suggestions convey desires for a variety of forms to support, fit, and adorn bodies in inventive ways.

Meanwhile, as a Hip Hop artist and community organizer in Seattle, Kevin hoped for the jacket to facilitate electronic music-making and performing—not just listening. He described his vision for more artistic and engaging interaction:

I would want to make it where it would be like making a beat... where you can go have the kick in the drum and the horn... and maybe you could tell the story. But having multiple layers so you can have somebody talking while you're making the beat... A few patches that are samples or drums and then you play your vocals on that separate patch, where you can do it all at once... That would be a little bit more performative, versus just tapping one patch, then standing there and listening.

Kevin is describing how he hopes to encounter electronic streetwear as an even more creative experience—for it to have more expressive capabilities for artists like himself to emcee and remix the contents in traditions of Hip Hop performance rather than only listen passively. Similarly, Rachel, a community organizer in Seattle, wanted to be able to remix and tailor the content to her local jurisdictions. She suggested designing patches like boombox hit clips that people could swap out to easily switch tracks on the front-end. She dreams of “having like 10 or 15 different story patches, and being able to add one and remove one, or being able to honor different people through having patches that can be put on, taken off, swapped out with other ones so that way it can continue to be mixed up, and people can even immerse themselves in the experience of designing the stories on the jacket.” In making the audio tracks easily changeable and makeable, she wanted to custom-design and ground electronic streetwear in the places where she organizes. Both Rachel and Kevin drew inspiration from other electronics (a boombox and music mixer) in communicating higher hopes for the streetwear.

While Kevin and Rachel hoped for the streetwear to be more re-mixable, Marvin spoke to how he envisioned it as a two-way rather than one-way communication channel that could also record social interaction with people. He said:

If there were a way that this jacket could also capture information, it would be cool... I found when I was working on murals, particularly on the streets when people have access to me, that I had the most interesting conversations with people that I otherwise would never know... It has been reaffirming for me, for the human spirit, to know that there are people that are impacted by art and seeing someone else in your community that is trying to help—if it were possible to engineer it that way to also be used for capturing stories.

While other interlocutors spoke to how electronic streetwear might allow people wearing it to connect with storytellers in a one-way listening channel, Marvin dreamed of a way for people to talk back: a two-way connection for fostering dialogue and story-sharing between people across places and spaces. Altogether, these creative visions hold potential to create a richer experience for interactors and artists whose work is materialized within the textiles.

4.3 Electronic Streetwear in Urban Space

Some interlocutors had contrasting ideas around questions of whom electronic streetwear ought to be for with respect to race and where it ought to be situated in urban space. We explored this question with our Black interlocutors in particular because of how the jacket foregrounds Black histories. Discussing possibilities raised critical questions surrounding who should wear or encounter it and in what places. Viewpoints differed in terms of whether it ought to focus only on Black communities versus work to build a multi-racial coalition. While Ariel voiced the import of only Black communities wearing it, Rose and Marvin agreed but with caveats that some non-Black people might also meaningfully engage with electronic streetwear. Meanwhile, Richard described how framing urban inequities foregrounded in the jacket, namely houselessness, as a class rather than racial struggle might make a greater impact.

Ariel spoke to how the jacket concerns positionality in particular ways. She questioned what it might mean for Black versus non-Black people to wear or encounter it. She said that she felt strongly about it being for Black people because of how it could otherwise be co-opted, explaining:

There's always this ickiness I feel around... that liberal POV of... if white people just heard more stories of Black suffering... then they would care... If this were placed in a space that was patronized by white people, the project then becomes or feels like that is what it is being instrumentalized to do like: ‘Oh this is just a way to help white people empathize with the Black struggle’... It feels like its rightful place is in the communities whose stories it centers and that its function is to be a tool for them to feel witnessed, seen, connected, but the jacket is not a vehicle to make non-Black people care.

Ariel is describing both the importance that it is Black people with personal connections to the histories (racially and spatially) who wear the jacket, and the pitfalls of people with non-Black identities wearing it. To protect its integrity, she saw the jacket as rightfully belonging at a place like the African-American Art and Culture Complex or a Black community center (e.g., a YMCA) in a San Francisco neighborhood where some of the stories are situated. While suggesting that this might appropriately position the jacket, she also voiced concerns about how public spaces cannot “control” who enters and engages with it.

Marvin and Rose voiced related concerns around how the jacket could be co-opted, but also expressed potential for non-Black audiences to meaningfully interact with it. Marvin said:

I was initially being like someone who would be wearing this would be someone from the [Black] community... But if it wasn't someone from the community... they could be doing some canvassing work for the project... Why not wear it if you could use it in a way that would help you connect with people to maybe make a difference with the issue? I wouldn't take it off the table.

While Marvin later added that the jacket “could be anywhere” but with the risk of “co-opt[ation] for commercial use,” Rose had shared concerns. She reflected on how she worried about the zine becoming just another “book on white people's coffee table” and viewed the jacket as potentially holding a similarly undesirable fate. Rose emphasized a tension between fashion aesthetics and public exhibition. She first thought about how museums often exhibit Black art and how the jacket might spark meaningful conversations in public spaces. But then she voiced more uncertainty around how fashion aesthetics might be reductive and superficial. Rose said:

I think there's public or some semi-public spaces that this can be in, and people could come and engage with it... But... aesthetics in fashion is a real challenge in terms of just the whole intent being reduced to just aesthetics... or just signaling... and not really about learning about these issues, empathizing, and wanting to have conversations about doing justice work... I would hope that non-Black people might question their desire to just put on a jacket like this and walk around.

Rose is voicing concerns around how non-Black people might appropriate the jacket for voyeuristic exhibitionism by exploiting it as a spectacle. She is also describing how fashion aesthetics, in particular, lend themselves to forms of surface-level engagement, which might be incompatible with deep reflection about systemic inequities. This augments what Kevin said with respect to Hip Hop and the tendency for Black culture to be “commodified and sanitized and diluted in a way where it evolves into something that is the opposite of what it originally was.” While both Rose and Marvin saw potential for the jacket to engage self-reflexive patrons and advocates of all races in justice work, they also relayed hesitation about how non-Black people might degrade or exploit its affordances.

Meanwhile, for practical reasons, Richard felt strongly about the jacket not only engaging but also representing audiences of all races to build a larger coalition. First, Richard suggested that the jacket include patches with faces and stories of people who are not Black because of how US urban inequities like housing are about race and class. He explained why he viewed this as a practical distinction based on his years of houselessness and decades of activism.

A face of somebody who's white sharing a story... is important because... housing... has always been a race and class issue... We saw the government react because middle class white women were being forced out of their homes in the Bay Area and were living in tents. And all of a sudden the government was like ‘Oh, my God’... It's important to bring in different racial and ethnic backgrounds into the storytelling because... it raises awareness that this is happening not so much to a specific group of people, but to a lot of people... Maybe it is another jacket that is interracial...

Richard thus thought that, for practical reasons, incorporating more diverse groups in electronic streetwear endeavors might make it more effective at persuading people in power with a bigger coalition. Moreover, he shared his ideas for organizers who are protesting on the streets and in multi-story buildings, as well as people who have lived without housing, to wear it. In framing housing as also a class struggle, Richard suggested that people of all races should be represented in and invited to wear electronic streetwear insofar as they are inhabiting and organizing on the streets.

5 DISCUSSION

Our project has examined how an artifact that plays stories, poetry, and music while worn on the body might open alternative horizons for urban life and spatial formation. We learn how digital forms of mobilizing are not separate from organizing work, but rather entangled within its threads. We further find that electronic streetwear (and other social justice-oriented e-textiles projects) require tailoring for a plurality of forms, including place-based relations, local movements, as well as diverse bodies and aesthetics.

By analyzing the jacket as situated in urban spatial and racial formations, we identify conflicting potential roles and trajectories within US social movements. A main tension traces back to how some interlocutors viewed the jacket more as a speculative garment (in line with artistic exhibition), while others interpreted it more as a community organizing instrument (e.g., a tool or product). While these two types of designs can overlap and exist at once, they also call for different responsibilities and consequences. Another tension surrounds how e-textiles require significant resources and knowledge that can be elite and exclusionary within maker cultures. In our case, we had institutional support to commission the jacket. But how might grassroots social movements practice e-textiles in low-resource conditions without that support?

Next, we unpack how street fashion gets implicated in these tensions around social movement material and what role wearables might play in community-driven computing infrastructures more broadly. We examine these questions as two interconnected opportunities for design research: (1) learning from textile legacies and solidarities to recognize—not rehearse—damage; and (2) examining what the “e” in e-textiles brings to social movements.

5.1 Textile Legacies and Solidarities to Recognize—Not Rehearse—Damage

We see opportunities for using e-textiles design practice to engage solidarities and legacies of practice that have long helped heal damage-centered research traditions. By damage-centered research, we refer back to what Tuck defines and critiques as “research that intends to document peoples’ pain and brokenness” [105], which community-based design scholars have also called for moving beyond [103] and rethinking [48]. One problem with documenting people's pain and brokenness is that researchers may reproduce that suffering by holding those impacted responsible for the oppression that they are experiencing rather than those in positions of power. In the context of housing insecurity, this insight would mean holding the racial capitalist system to account, which is a seemingly insurmountable task for an e-textile artifact.

One reading of Tuck's argument focuses on the rehearsing of painful lived experience and the suggestion that in this rehearsal the researchers take aspects of agency and personhood away from the people whom they study. As poignantly exemplified by the arpilleras that women crafted in Chile under the Pinochet dictatorship [2], textiles practices can facilitate resistance, community-building, storytelling, and trauma processing.Examples of historical textile-based storytelling such as these illustrate how one's self-documentation of their own lived experience, often through creative means, can make visible otherwise hidden stories and elevate the people who tell them. For design research, this connection suggests engaging with a wider range of textile histories as ways of expanding and critically interrogating design legacies. This suggestion offers a provocation for engaging genealogies of textile practices that feminized and minoritarian groups tend to practice.

Further, in her open letter to communities, Tuck uses the story of youth coveting a particular pair of sneakers (a streetwear staple) while critiquing capitalism as a way to call for a desire-based (rather than damage-based) approach to research that recognizes the complexities and contradictions of people. This approach is meant to center people's hopes and dreams in spite of oppression. Building wearables specific to housing advocacy, Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko introduced the 1991 Poliscar as a tank-like vehicle with a rotating top that conjured enhanced mobility, protection, shelter, and community for people without homes. While augmenting the public visibility of an ongoing housing crisis, Wodiczko's design also integrated a suit of networking tools designed to facilitate connections among people debased by the crisis. Drawing parallels with this gesture, our wearable probe invites analysts to consider what spatial engagements it supports that align with and differ from social movement strategies. For example, beyond drawing connections between distinct social geographies, which aspects of social movement action does this artifact emphasize? Recall that Rachel suggested making the probe adaptable to local narratives by simply changing the tracks or patches. While Jodi proposed wearing it at a rally, others recommended door-to-door campaigns. A garment used as an organizing tool achieves more effective outcomes by knocking on doors where the interactions are calmer and more personal might prove more effective than a garment used in large protests where multiple sensory inputs compete for recognition and visibility. Our rendition of electronic streetwear, like the sneakers and Poliscar vehicle, is implicated in the very same fraught global supply chains it helps challenge, with some of the audio tracks even narrating related harms as told from first-hand perspectives. Yet, the jacket also embodies joyful memories and music, which our interlocutors such as Ariel emphasized as essential elements to not only define people by one-dimensional (uncomplex) stories of struggle. What we make of this contradiction comes in part from the way that our interlocutors described community-engaged work with social movements as requiring both acknowledgments of harm (documenting untold histories that can include traumas of urban displacement and eviction) as well as joyous acts of remembering and imagining otherwise.

By placing textile lineages within computing conversations that emphasize scale, precision, and empiricism, we face a similar potential. As if heeding to Tuck's call, our interlocutors described the multi-dimensional audio tracks speaking for themselves by voicing interlocutors’ desires: their hopes and dreams for electronic streetwear, as well as their speculations as complex souls and beings [49]. This interleaving of devalued textile legacies alongside computing work allows us, as design scholars, to sit with our interlocutors’ (and own) sometimes conflicting desires between speculating about alternative design futures and organizing against ongoing harms. It does this in part by “exposing realities” [67] around devaluation that consistently discount and minimize embodied knowledge. But it also offers this opportunity for reflection by building from the foundational work of Remendar lo Nuevo (Mending the New) [19, 21, 74, 75, 76, 78] in their use of e-textiles embedded with digital oral histories to support communal forms of processing grief. With this project in mind, we consider how e-textiles-making and its histories can create communal spaces that operate as “improvisational technologies of healing” [76]. We look to this notion of mending, as in healing—not resolving or solving, but rather co-processing and rebuilding damage-based research.

5.2 What the ‘E’ in E-Textiles Offers Movements

In the shadow of traditional storytelling practices, what electronics offer the design spaces of textiles and social movement organizing requires further attention. As we know from craft scholarship, textile practices have long offered capacious opportunities for storytelling and refusal, opening spaces for community organizing and driving the development of social movements [12, 15]. As many design studies have shown, technological advances can be problematic, harmful, and detested. For instance, Daniela Rosner reflects on how in designing Spyn, a mobile phone software for knitters to record their handcraft process, older knitters resented it for rivaling their overlooked work with technology (e.g., luminescent wires) and even threatening to displace them by exposing aspects of their craft expertise that they wanted to remain a secret [90, 91, 92]. Similarly, in remediating oral storytelling traditions into a conversational storytelling agent, Brett Halperin and colleagues found that AI holds potential to harmfully rival oral historians by displacing them as well [46]. What is more, limits to access and barriers to funding around technologies like e-textiles make such design practices not always feasible, desirable, or sustainable for grassroots projects. Working with e-textiles and other technologies in these contexts requires addressing the asymmetries in power, as well as responsibilities around skills-sharing, maintenance, and repair.

In reflecting upon what e-textiles then offers relative to other forms of media, we revisit what Bolter and Grusin theorize as remediation, in their words: “Digital visual media can best be understood through the ways in which they honor, rival, and revise linear-perspective painting, photography, film, television, and print” [9]. They further describe how, in remediating particular media (e.g., replacing, improving, remixing, or absorbing it), emerging technology can present aesthetic and economic “competition” [ibid, p.48]. In other instances, Bolter and Grusin describe this process as refashioning, using a textile metaphor to underline a shift from what we see as rivalry (creating something better) into an alternative register of reworking (making into something new). What then might it mean for e-textiles to refashion, but not rival textile-storytelling and, in this case, a print zine?

In contexts of counter-storytelling, we find digital augmentation of fabric brings a particular energy and social-performative capacity to housing justice discourse. Imagining staged performance alongside modest engagement, our interlocutors described a range of settings in which the jacket might open opportunities for enlivening their community organizing work along new axes. In the design process, we considered how electrifying textiles and reformatting a print zine accordingly can engage more bodily senses (i.e., sound) as well as social performances. We learned from our interlocutors that relative to the zine, a garment can provide comfort and bring people's stories to life rather than represent them as disembodied text or data points (e.g., on a map). Meanwhile, relative to analog textiles, a wearable allows for carrying and socializing audible stories while moving through places and spaces. These augmentations suggest that perhaps we could have even gone even further in reworking other aspects of the legacy media. For instance, in hindsight, we could have complicated Marie Harrison's periodization imprinted in the zine and translated into the jacket to memorialize her through dates of birth and death. As provocated in soulful speculation, a method that Brett Halperin and Daniela Rosner develop to consider the soul in design processes concerned with healing, people's souls are alive long before birth and after death; yet, design modes of understanding users, participants, and people often hinge on these enlightenment birth-death logics [49]. Rather than reproducing these logics, we could have troubled them more to weave new modes of electronic and spiritual signification.

That said, the print zine in its own form and textiles in their tried-and-true form without the weight or baggage of electronics bring other strengths to social movement organizing. We do not suggest that any one form is superior. Instead, we look to understand what electronic augmentation and remediation offer. Especially in light of the long historical traditions associated with textiles storytelling, we urge design scholars to consider how the work of refashioning turns oral and musical stories into new and different augmented practices—in this case, dynamic features and social performances that might enliven and electrify social movements as a collective body charged with resistive power in all senses of the word.

6 CONCLUSION

Across interviews and ongoing dialogues with 10 community partners, we investigated how the materiality and potentiality of electronic streetwear might open new pathways for social movements. Our interlocutors sometimes positioned the wearable as a site for helping to improve housing conditions or to amplify existing advocacy work, perceiving it as a community organizing instrument. Others positioned the wearable as means of imagining community organizing as an embodied sonic exercise, interpreting the probe as a speculative garment. We examined this tension between designing a practical tool for harm reduction (instrumentation) and designing to open up questions of hopes, dreams, and soulful connections around housing justice (speculation). We urge design scholars to unearth new possibilities for interweaving e-textiles inquiry with social movement practice and performance in ways that help damage-centered research move toward communal healing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We extend our greatest possible thanks to all of the incredible community partners, artists, and narrators whose voices comprise Resistive Threads, including the CHANNELS team, Gabrial Thompson, Marcus Moore, Marie Harrison, Raymond Tompkins, and Robin Bean Crane. We extend our deepest gratitude to the entire AEMP (Dis)location Black Exodus team, Be:Seattle, Rolla Renters Association, and Washington Community Action Network for their integral partnerships. Additionally, we sincerely thank Erin McElroy, Doenja Oogjes, Claire Florence Weizenegger, our anonymous reviewers, and colleagues at the CHI ’23 Body x Materials workshop for helping strengthen this manuscript. We also want to warmly thank Adrienne Hall, Alexandra Lacey, Ariana Faye Allensworth, Colby Bariel, Esteban Agosin, Kathleen Dargis, Mark Harris, Javonne Barrett, Jin Zhu, Jodi Craft, King Khazm, Rashell Lisowski, Rayna Abston, Sylvia Heisel, Tanya Moore, and Zack Pockrose. This study was graciously funded by the University of Washington Urban@UW Initiative, as well as the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. DGE-2140004 and NSF Grant No. 2222242. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed throughout this material are those of the co-authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

REFERENCES

- King Adz and Wilma Stone. 2018. This is not fashion: Streetwear past, present and future. Thames & Hudson London.

- Marjorie Agosin. 1987. Scraps of life: Chilean arpilleras: Chilean women and the Pinochet dictatorship. Zed.

- Christine Andrä, Berit Bliesemann de Guevara, Lydia Cole, and Danielle House. 2020. Knowing Through Needlework: curating the difficult knowledge of conflict textiles. Critical Military Studies 6, 3-4 (2020), 341–359.

- Mariam Asad. 2019. Prefigurative design as a method for research justice. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 3, CSCW (2019).

- Mariam Asad and Christopher A. Le Dantec. 2015. Illegitimate Civic Participation: Supporting Community Activists on the Ground(CSCW ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1694–1703. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675156

- Giacomo Bazzani. 2023. Futures in action: expectations, imaginaries and narratives of the future. Sociology 57, 2 (2023), 382–397.

- Gabrielle Benabdallah, Michael W Beach, Nathanael Elias Mengist, Daniela Rosner, Kavita S Philip, and Lucy Suchman. 2023. The Politics of Imaginaries: Probing Humanistic Inquiry in HCI. In Companion Publication of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. 131–134.

- Gabrielle Benabdallah et al.2022. Slanted Speculations: Material Encounters with Algorithmic Bias. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference.

- Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding new media. mit Press.

- Kirsten Bray and Christina Harrington. 2021. Speculative blackness: Considering afrofuturism in the creation of inclusive speculative design probes. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021. 1793–1806.

- André Brock. 2018. Critical technocultural discourse analysis. New Media & Society 20, 3 (2018), 1012–1030.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson. 2017. Fray: art and textile politics. University of Chicago Press.

- Hillary Carey. 2023. Social Design Dreaming: Everyday Speculations for Social Change. Temes de Disseny39 (2023), 72–91.

- Hillary Carey and Alexandra To. 2023. “Lots Of Extra Time and Privilege To Just Dream Of Utopia”: Barriers To Long-Term Visioning In Racial Justice Work. Journal of Futures Studies (2023).

- Christina Chau and Sky Croeser. 2023. Weaving in the Threads. M/C Journal 26, 6 (2023).

- Elizabeth Chin. 2022. Speculating spiritual technologies. Interactions 29, 4 (2022), 60–61.

- Jean Ho Chu and Ali Mazalek. 2019. Embodied engagement with narrative: a design framework for presenting cultural heritage artifacts. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 3, 1 (2019), 1.

- Adele E Clarke, Carrie Friese, and Rachel S Washburn. 2017. Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Sage publications.

- Laura Cortés Rico, Jaime Patarroyo, Tania Pérez Bustos, and Eliana Sánchez Aldana. 2020. How can digital textiles embody testimonies of reconciliation?. In Proceedings of the 16th Participatory Design Conference 2020-Participation (s) Otherwise-Volume 2. 109–113.

- Sasha Costanza-Chock. 2020. Design justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need. The MIT Press.

- Tomas Sanchez Criado and Adolfo Estalella. 2023. An Ethnographic Inventory: Field Devices for Anthropological Inquiry. Taylor & Francis.

- Jay Cunningham, Gabrielle Benabdallah, Daniela Rosner, and Alex Taylor. 2023. On the grounds of solutionism: Ontologies of blackness and HCI. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 30, 2 (2023), 1–17.

- Ella Dagan, Elena Márquez Segura, Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Miguel Flores, Robb Mitchell, and Katherine Isbister. 2019. Design framework for social wearables. In Proceedings of the 2019 on designing interactive systems conference. 1001–1015.

- FE Russell Davis and Changi Rach. 2004. The women's response to internment. The Internment of Western Civilians Under the Japanese, 1941-1945: A Patchwork of Internment 24 (2004), 115.

- Laura Devendorf, Kristina Andersen, and Aisling Kelliher. 2020. Making design memoirs: Understanding and honoring difficult experiences. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–12.

- Laura Devendorf, Joanne Lo, Noura Howell, Jung Lin Lee, Nan-Wei Gong, M Emre Karagozler, Shiho Fukuhara, Ivan Poupyrev, Eric Paulos, and Kimiko Ryokai. 2016. "I don't Want to Wear a Screen" Probing Perceptions of and Possibilities for Dynamic Displays on Clothing. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 6028–6039.

- Christine Dierk. 2020. Heirloom Wearables: A Hybrid Approach to the Design of Embodied Wearable Technologies. University of California, Berkeley.

- Jill P. Dimond, Michaelanne Dye, Daphne Larose, and Amy S. Bruckman. 2013. Hollaback! The Role of Storytelling Online in a Social Movement Organization. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (San Antonio, Texas, USA) (CSCW ’13). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1145/2441776.2441831

- Lynn Dombrowski, Ellie Harmon, and Sarah Fox. 2016. Social justice-oriented interaction design: Outlining key design strategies and commitments. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems. 656–671.

- Felix Anand Epp, Anna Kantosalo, Nehal Jain, Andrés Lucero, and Elisa D Mekler. 2022. Adorned in memes: exploring the adoption of social wearables in Nordic Student Culture. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–18.

- Sheena Erete, Jessa Dickinson, Caitlin Martin, Anna Bethune, and Nichole Pinkard. 2020. Community conversations: A model for community-driven design of learning ecosystems with geospatial technologies. (2020).

- Sheena Erete, Emily Ryou, Geoff Smith, Khristina Marie Fassett, and Sarah Duda. 2016. Storytelling with Data: Examining the Use of Data by Non-Profit Organizations(CSCW ’16). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1273–1283. https://doi.org/10.1145/2818048.2820068

- Bonnie Fan and Sarah E. Fox. 2022. Access Under Duress: Pandemic-Era Lessons on Digital Participation and Datafication in Civic Engagement. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 6, GROUP, Article 14 (jan 2022), 22 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3492833

- Laura Forlano. 2013. Making waves: Urban technology and the co–production of place. First Monday (2013).

- Laura Forlano and Dharma Dailey. 2008. Community wireless networks as situated advocacy. Situated Technologies Pamphlets 3: Situated Advocacy (2008).

- Sarah Fox, Mariam Asad, Katherine Lo, Jill P Dimond, Lynn S Dombrowski, and Shaowen Bardzell. 2016. Exploring social justice, design, and HCI. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 3293–3300.