Domestic Cultures of Plant Care: A Moss Terrarium Probe

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3715336.3735689

DIS '25: Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Funchal, Portugal, July 2025

Houseplants are increasingly being used as part of interactive systems that aim to foster pro-environmental concern and awareness of more-than-human life. Yet such interventions rely on conflicting and untested assumptions about how people relate to houseplants. We therefore studied domestic plant care in 11 purposefully sampled households, applying a sensor-equipped moss terrarium as a living ‘thing ethnography’ probe, supplemented with semi-structured interviews. We find that social and intergenerational cultures of plant care inform people's individual concern and accountability through constituents and mechanisms like gift-giving, signalling, knowledge transfer, or joint practical care. We identify five domestic cultures of plant care in our sample, each of which frames plants differently and leads to different practical approaches to plant care. We propose design considerations that emphasise enculturation and shared care over individual behaviour change and reframe houseplants from decorative objects into living household members.

ACM Reference Format:

Nirit Binyamini Ben-Meir, Patrick G.T. Healey, and Sebastian Deterding. 2025. Domestic Cultures of Plant Care: A Moss Terrarium Probe. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS '25), July 05--09, 2025, Funchal, Portugal. ACM, New York, NY, USA 19 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3715336.3735689

1 Introduction

Using plants in human-computer-interaction (HCI) has been growing over the last 30 years into a distinct field of human-plant interaction (HPI) [73]. Researchers and designers have justified such work with plants in various ways [54]. Initially, works tended to employ plants as engaging or calming interfaces or ambient displays, placing them in a more auxiliary role [14, 17, 18, 21, 61, 70, 76]. However, there has been a gradual shift towards a more eco-centric approach, viewing plants as living beings that need care, and developing tools to augment their signals [1, 23, 37, 40, 42, 85]. This shift intersects with growing interest in more-than-human perspectives [15, 30, 81] and ethical considerations of nature in HCI [22]. It also aligns with moves toward sustainable interaction design (SID) [5] and sustainable HCI (SHCI) [19] that aim to promote working with nature rather than controlling it [52], or citizen science and slow technology which match design with living organisms and plants [50].

Much HPI research concerns plants, and particularly houseplants, as a means and/or end of digital behaviour change to drive pro-environmental behaviours and attitudes [54]. In this, HPI researchers have relied on varying and often contradictory assumptions and theories of change. Some presume that people spontaneously appreciate and care for plants and therefore use plants as motivational drivers for behaviour change [7, 35, 68]. Others presume ‘plant blindness’: people tend to overlook plants and lack care for them; HPI therefore needs to computationally amplify plant signals to communicate their needs more clearly [3, 36, 40, 78] to drive plant care.

These opposing assumptions have been discussed [54] but remain largely empirically untested. More-than-human HCI has begun to use ethnographic and designerly methods to trace entanglements between humans, material objects, and other species [15, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31, 79, 80], or study people's sensitivity toward and noticing of the signals of living systems [40, 50, 64, 66, 82]. However, this still leaves unanswered how intervening in households by introducing new houseplants affects plant care, and what personal and situational factors shape people's care for and sense-making of houseplants in domestic settings and thus, the effect of any design intervention.

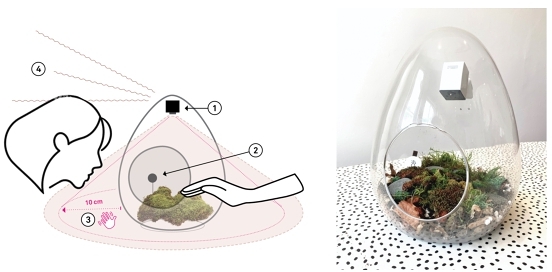

To build this missing understanding, we conducted a living thing ethnography [29] to investigate people's daily interactions with a moss terrarium they hosted. Using qualitative data analysis [58], we analysed mixed data from a purposive sample of 11 households and 2 additional interview-only participants. We designed and deployed moss terraria with sensors and a motion-activated camera (fig. 1) as a minimal intervention probe to record daily in-situ plant care and the arrangements around it over two weeks, accompanied by semi-structured interviews on participants’ experiences with the terrarium and their sense-making of houseplant care in general.

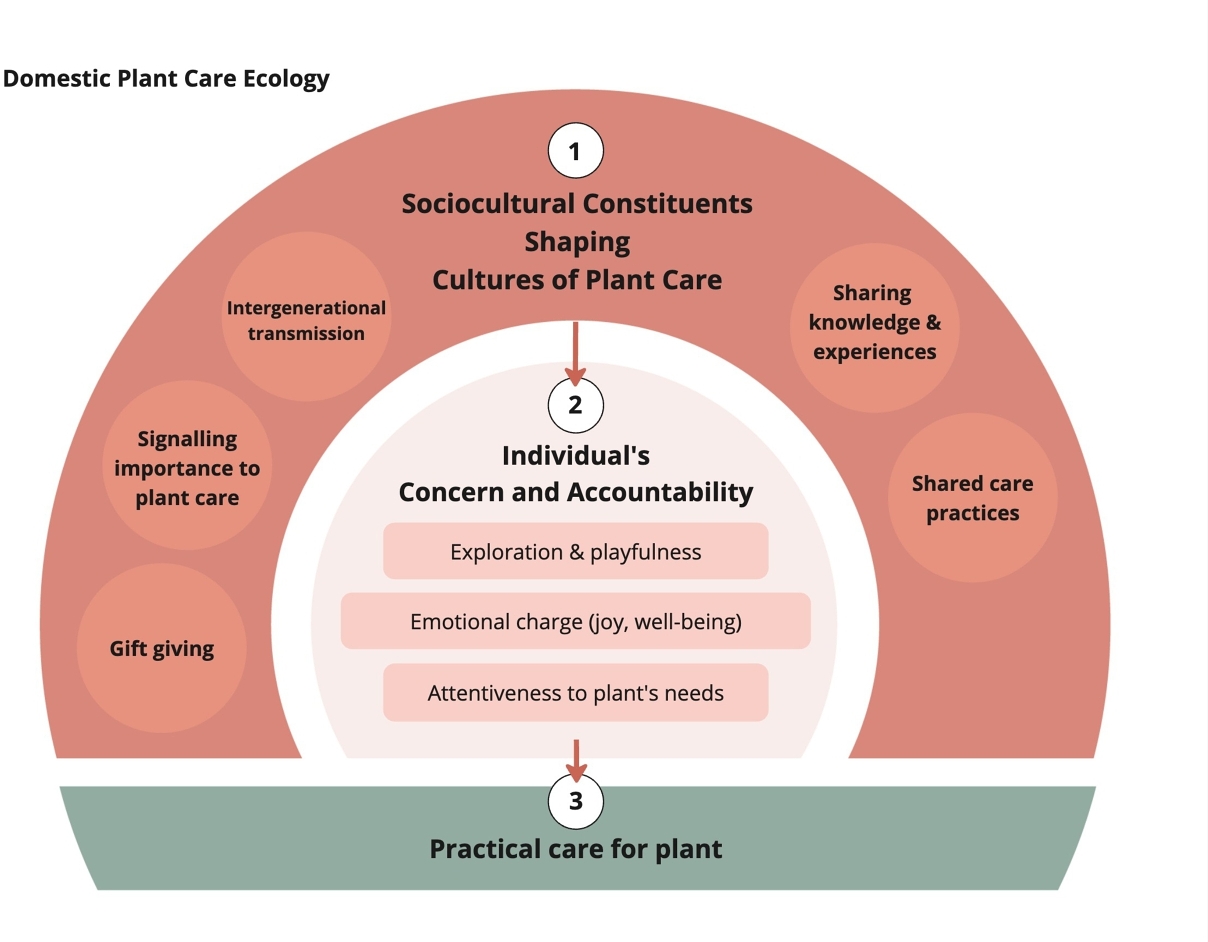

We identify a domestic plant care ecology that drives plant care mediated by an individual sense of concern and accountability that comprises attentiveness to plant needs, emotional charges, and exploration and playfulness around learning a plant's signals. Importantly, this individual concern is embedded in and reproduced by social and intergenerational cultures of plant care, including constituents and mechanisms like gift-giving, signalling the importance of plant care, sharing knowledge and experiences, shared care in practice, and intergenerational transmission: people are often enculturated into plant care during childhood. Further, we present five domestic cultures of plant care, which can be framed as as different ways of enacting and understanding houseplants: as (a) a chore, (b) precious living ornaments, (c) a prompt for bonding, d) a member of the milieu, and (e) an interconnected part of the family's ecology. We elaborate on how social factors constitute and impact these cultures and related attitudes and propose considerations for future HPI design based on these insights.

Our work contributes to DIS and HCI communities by (a) building background knowledge about domestic cultures of plant care to inform future HPI design; (b) challenging prevalent (if often implicit) HPI theories of change that focus on short-term changes targeting individuals, arguing that effective interventions may have to target longer-term social and intergenerational enculturation; (c) identifying social and family cultures of care as entanglement nodes and dynamics worthy of attention to more-than-human HCI more generally; (d) applying and reflecting on thing ethnography as a method involving a living thing.

2 Background

2.1 Houseplant and terrarium research

Houseplants are the most commonly used kind of plants in HPI research [54]. They represent one of the few remaining opportunities for daily interaction with plants in urban life, especially for those who do not have access to a garden. Caring for houseplants connects with many broader socio-cultural factors linked to ecological stewardship, such as social norms, values, literacy, experience, and practice [16]. Yet while psychological and ethnographic work has explored the complex relationship between people and plants within gardens or parks [41, 44, 45], houseplants have received much less investigation.

Houseplants often function as aesthetic or decorative objects that symbolise a particular social identity and lifestyle. This is still evident today in commercial contexts, where houseplants are often treated as decorative objects or commodities, purchased from furniture stores or supermarkets. It is also a common narrative in current houseplant how-to guides and coffee table books. This continues a sociocultural and economic tradition of houseplants as bourgeois displays of wealth and sophistication [39, 56, 67]. The invention of the plant terrarium by Ward in 1829 revolutionised plant transportation and further enriched this tradition of cultivating plants indoors. During the Victorian era, terrariums became a popular decorative element in homes, enabling people to enjoy exotic plants in domestic settings [43]. Today, moss terrariums attract new attention, appreciated as miniature ecosystems and tiny gardens [60].

Houseplants continue to be identified with health and well-being benefits, both in popular literature and environmental psychology [9]. Houseplants can improve the quality of the indoor environment, especially air quality [2]. Beyond that, the Covid-19 pandemic saw a significant rise in houseplant popularity [51] and claims about how houseplant care might mitigate loneliness and disconnection from nature during lockdowns [20, 63, 65].

In addition to such supportive qualities and benefits, houseplants are often positioned as part of a caring relationship. Although “plant parents” express attachment to their plants as living beings [10], recent studies highlight the poor record of houseplant care, with estimates that over 50% of houseplants die within a year of purchase in their owners’ homes [75]. Thus, the symbolic value accorded to plants is at times at odds with at least some people's actual practices. This gap between values and actions is commonly discussed in studies of pro-environmental behaviour in general [4, 59], but it is less well understood what generates it in the case of domestic houseplant care.

2.2 Human-Plant Interaction

A number of recent reviews have synthesised the state of HPI research in HCI. Zhou and colleagues [87] developed a taxonomy for the roles of technology in biodesign, particularly in relation to co-habitation with non-human entities. Chang and colleagues [11] mapped design concepts of application contexts, interaction modalities, and the like. Fell and colleagues examined plant-related HCI projects through a biocentric ethical lens, finding that most HPI work in HCI is anthropocentric and lacks ethical respect for nature toward the plants involved. [22]. Most recently, Loh and colleagues [54] have analysed the literature from a critical more-than-human perspective. They identify three forms of entangling plants: as proxies for nature, triggers for human behaviour and experience, and as interfaces. They find that HPI interventions overwhelmingly frame plants as utilitarian objects, not co-inhabitants. Notably, these reviews analyse how HCI researchers use and conceptualise plants, not how the actual people engaging with HPI systems (i.e., the study participants) conceptualise plants and care for them (or not). Nor do they unpack what factors shape everyday people's engagement and sense-making around houseplants. This matters particularly because current design interventions using houseplants as triggers for human behaviour [54] are grounded in conflicting implicit assumptions – somewhat simplified, whether people ordinarily manifest ‘plant blindness’ or ‘plant love.’ Flawed assumptions are likely to lead to flawed starting points or targeted levers of change in design (e.g., ‘just digitally foreground the plant's health status’) and ultimately, ineffective interventions.

In more recent more-than-human HCI, several studies have unpacked different forms of sensibility toward or noticing of plants that people manifest spontaneously or in response to design interventions [36, 64, 66]. Poikolainen Rosén, Normark, and Wiesen's participant [64] and speculative design [66] ethnographies with urban farmer communities developed a model of noticing and three approaches to noticing the environment: controlling the environment, developing sensibility to its state, and just being and appreciating. Hansen and colleagues [36] identified three kinds of sensibility toward plants that their design interventions could elicit: hermeneutic, existential, and socio-cultural. These studies bring welcome attention to human plant sensitivity as one dimension of plant care. Yet they do not unpack the personal and situational factors that give rise to noticing in some people but not others – which present useful points of intervention for design.

2.3 Ethnographies of Care for Non-Humans

Previous work has developed grounded understandings of care in the context of living with and caring for domestic microbes. Chen and colleagues describe the ethnographic accounts of six participants who spent 10 days taking care of, talking to, and being addressed by the Nukabot, a food-fermenting bucket with microbes. They analyse their experiences through three ethopoietic elements of care: maintenance, affection, and obligation [12]. Zhou and colleagues offer extensive empirical insights on what motivates individual care for a novel life form - a photosynthetic microbial living artefact - in domestic contexts. Participants lived with and cared for the artefact for two weeks, knowing its air-freshing functionality. The identified motivations of care include livingness, curiosity towards a new life form, joyful interactions and mutualism [88]. Jasmine Lu and Pedro Lopes explore how a living slime mold that embedded as a functional component of an interactive smartwatch device changes user-device relationships enhancing the sense of reciprocity and responsibility towards the organism [55]. Our study extends these explorations to houseplants—organisms that are even more commonly seen in everyday life—and considers care within broader social and cultural contexts. Furthermore, while the above-mentioned works have not incorporated the perspective of the living organism itself, this study complements existing approaches by including data collection from a ’thing perspective’, offering insights through a more-than-human lens.

In sum, much HPI aims to develop interventions that foster eco-centric sensitivities and behaviour toward plants, yet with conflicting and empirically untested assumptions about people's existing everyday relation to houseplants. Existing research outside HPI offers little insight into these daily practices and perceptions of houseplant care and the factors that shape them. Some more-than-human work has begun to chart everyday plant sensitivities and care relations with microbial organisms, still there is a need for empirical understanding of the personal and contextual factors that shape existing everyday domestic plant care as the baseline for any contextual design intervention. In this study, we therefore aimed to understand how domestic plant care toward a newly introduced plant unfolds, and what personal and situational factors shape it.

3 Method

To answer our research question, we employed a qualitative approach using ethnographic methods. We use qualitative data analysis following Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña [58], emphasising inductive reasoning and the constant comparison of data to identify patterns, commonalities and differences, eventually proposing an explanatory causal model for phenomena identified in the data through data charting and modeling. For this, we collected and compared both observational data through a terrarium probe and verbal data from semi-structured interviews with participants.

3.1 The Moss Terrarium as "Co-Ethnographer" and "Minimal Intervention"

Capturing actually occurring human-plant relationships in everyday domestic contexts requires creative methodological tools. During the study design and pilot interviews, several considerations came to shape our approach. First, we aimed to capture a range of attitudes toward plants, ranging from enthusiastic caretakers to those indifferent to plants. Second, social desirability, post-rationalising, and participants’ lack of awareness of subtle or routine everyday interactions could impede capturing relevant behaviour through interviews since human participants may not consciously notice, recall, or wish to articulate them. This required methods that could record implicit behaviours with minimal researcher presence. Finally, domestic plant care is varied and distributed, often involving multiple household members at different times. To get an integrated picture, we needed to capture data from the single ‘point of view’ of the care-receiving plant, but in a privacy-conscious fashion fit for the insides of people's homes.

These considerations led us to Giaccardi's thing ethnography [29] and cultural probes [27, 33] to capture elusive activities in context and how people made sense of those activities [34, 38, 77]. Thing ethnography equips everyday things with a camera and sensors, thus challenging the common anthropocentric perspective of ethnography, instead capturing phenomena and relations from the thing's ‘point of view’ [29, 32]. By equipping a moss terrarium with camera and sensors of the moss's living conditions and health, we created a ‘living thing ethnography’ that allowed us to gently centre our attention on and through a house plant. Choosing a highly responsive moss whose health is easily outwardly visible to the human eye further aided this.

Notably, we introduced these moss terraria as a new plant to households. Thus, they also served as a ‘minimal intervention’ probe (fig. 1, fig. 3) – that is, one with minimal computational augmentation as compared to common HPIs. By integrating a new, less familiar plant into each participant's environment, we could examine participants’ propensity to explore and learn about its care. For participants with existing plant care practices, we could compare these new interactions with their regular routines. Finally, most domestic HPI interventions similarly deploy new plants in households, making this setup relevant for current intervention practice.

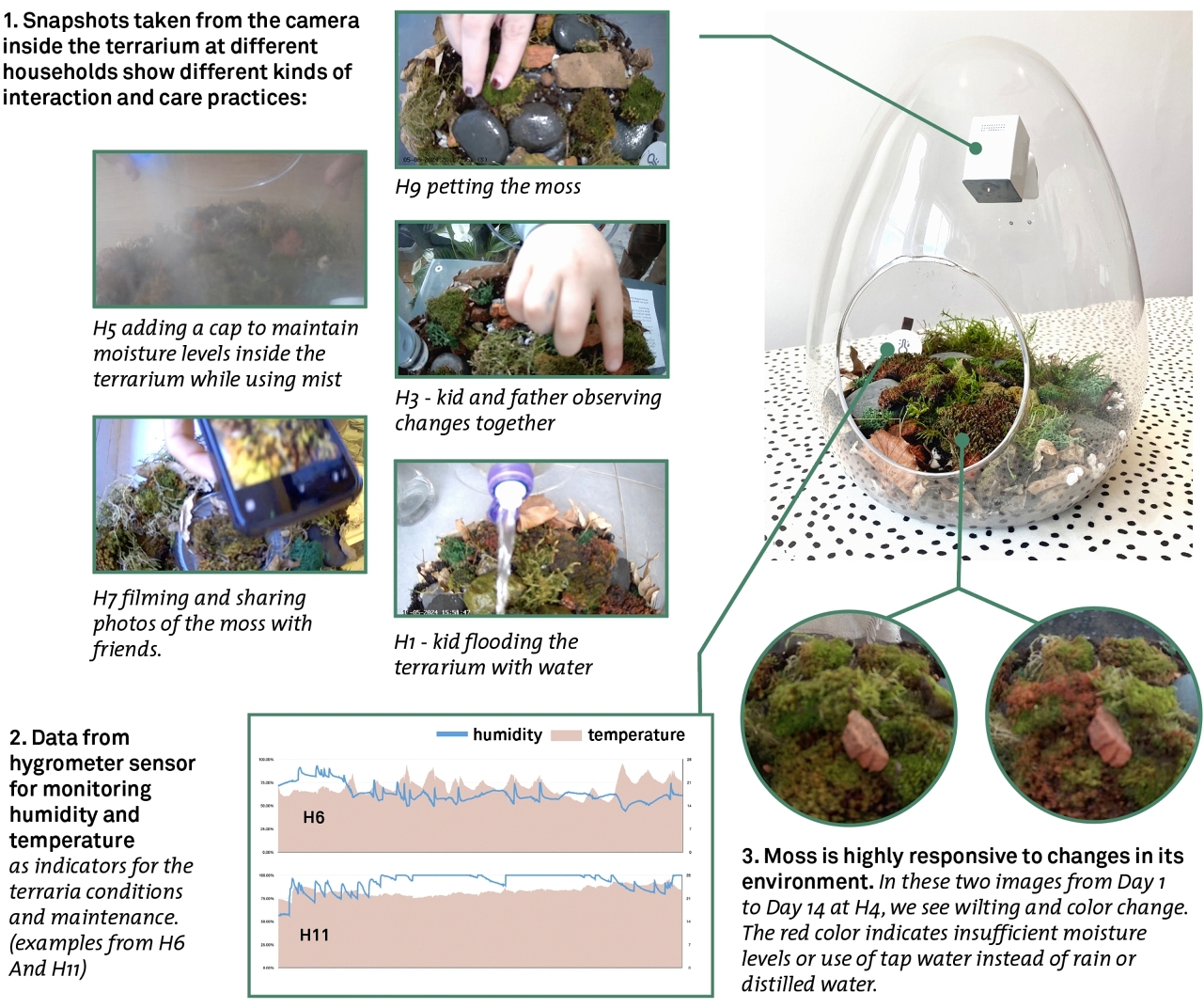

An unobtrusive motion-activated camera let us record direct interactions with the terrarium or plant care activities. This minimised researcher intervention while maintaining privacy by providing only a limited view around the terrarium and avoiding clear visibility of participants’ faces (fig. 1). The motion-activated camera started recording on detecting motion directly in the terrarium (see fig. 2 and fig. 4 for example stills). The narrow terrarium opening allowed for moving one's hand and the small water sprayer we provided into the terrarium, such that it would be video-captured. Additionally, daily still images of the moss were taken, and a hygrometer sensor captured environmental conditions inside the terrarium. (see full hygrometer readings in supplementary materials).

3.2 Which Mosses and Why

To encourage participants’ curiosity and close observation, we included a variety of moss types in each terrarium: three local mosses— didymodon vinealis (soft-tufted beard-moss), zygodon viridissimus (green yoke-moss), and calliergonella cuspidata (pointed spear-moss)— alongside cladonia rangiferina, commonly known as preserved reindeer moss, which is botanically classified as a lichen.

Our study is not the first HCI or design project to incorporate moss plants into interactive experiences, often drawing on their qualities as lush, living matter that symbolically represents nature [47, 74, 86, 89].

We here chose moss plants for four related reasons:

(a) The first author brings personal care for and expertise in moss thanks to several years of working with them in earlier art and design projects, which extend into the larger PhD project that this study is a part of (see full positionality statements in the supplementary materials). This personal care includes an appreciation for its vital ecological roles—serving as habitat for invertebrates and providing beds for seed germination, and thriving across diverse environments on every continent. Further, the first authors’ familiarity enabled more accurate analysis and assessment of the plants’ condition throughout the study, and informed the care practices that supported the mosses’ recovery and facilitated their return to their original habitat after the study concluded. Here, it helps that mosses are particularly remarkable for their resilience and can revive after long-term dormancy under extreme conditions.

(b) Mosses are highly sensitive to environmental changes and can provide immediate, visible feedback through shifts in colour and wilting, which makes them expressive of their surrounding conditions, the quality of care they receive, and their own wellbeing.1 Certain species, such as didymodon vinealis, are especially reactive: their leaves begin to close and brown within minutes of exposure to heat, dryness, or direct sunlight, and can reopen and regain their green colour within a minute of being misted (see Fig. 2 for examples). Though these changes may be subtle to the naked eye, they are perceivable for attentive plant carers and clearly visible in time-lapse footage or photo comparisons. This enabled us to monitor plant health and care using video documentation.

(c) Moss is less commonly kept as a houseplant and therefore less familiar to most participants. Moss terrariums create a contained microclimate primarily shaped by two key care factors—temperature and humidity—which are relatively easy to manage, teach, and measure. Unlike fully sealed, self-sustaining terrariums, the open design used in this study required participants to engage in daily care to maintain adequate humidity levels. Moss demands more attentive care than many common houseplants. All this offered an opportunity to observe how participants developed familiarity with it, learned to interpret its signals, and adjusted their care practices—even if they had no/different prior experience with other plants.

(d) Because mosses are non-flowering plants, they may not be perceived as aesthetically appealing, and their common presence in damp or neglected areas often leads to them being underappreciated or overlooked. Including moss in the probe allowed us to examine how participants responded to a plant that is not traditionally seen as ‘decorative,’ and to compare their attitudes and approaches toward different plant species.

From a more-than-human perspective, it is important to acknowledge that the moss plants may not have benefitted from all aspects of the study—for example, being kept indoors, receiving imperfect care, or being displaced from their natural habitats. The authors took care to minimise any long-term harm, actively supported the mosses’ regeneration, and aimed to return them to their original environments. At the same time, they believe that fostering public awareness of mosses—their signals, sensitivities, and unique characteristics—can enhance appreciation and protection of these often-overlooked species. In this context, involving moss in the study was seen as a way to help advance that broader aim.

3.3 Ethics and Procedure

The study received ethical approval from our institutional review board. Participants volunteered by responding to an open call sent to university staff and students and to a local school parents group. Participants and their household members completed informed consent forms, including permission to record and share pseudonymised data. Our screening survey asked about demographics (age, gender), family and household composition and interest and experience in gardening and houseplants. This allowed us to purposely sample participants.

The first author would bring the terrarium into a participant's household. Providing verbal and short written guidance on how to care for its plants. The terrarium remained in the household for a two-week period to collect recordings. Afterwards, it was retrieved, and the recordings were reviewed by the first and second authors before arranging a follow-up interview with the primary participant and any other household members willing to participate. All terrarium deployments and interviews took place between April 28 and August 9, 2024.

3.4 Participant sample

In total, we collected data from 13 single- and multi-person households spanning 34 household members across a large city in the United Kingdom; 11 households hosted a terrarium, plus two additional participants who were interviewed only, sharing their long experience in plant care (due to technical issues, the camera probe could not be installed at their homes) (table 1). Our final sample of lead participants (see table 1) varied in age (22 to 84), gender (8 women, 5 men), family status, household composition, and plant care experience. While all participants lived in the same city during the study, several were raised outside the United Kingdom, e.g., in Mexico, Germany, China, Brazil, India, and the Middle East. While nationality or home country were not collected during recruitment, many participants mentioned these details in their interviews. They also differed in occupations.

| ID | Household composition | Lead participant ID age and gender |

Occupation (Lead) | Plants owned |

Plant care experience |

| H1 | Couple with 2 children | P1, 40’s, Woman | Yoga teacher | 8 | Medium |

| H2 | Couple with 3 children | P2, 40’s, Woman | Marketing manager | 15 | Long |

| H3 | Couple with 3 children | P3, 40’s, Woman | GP doctor | 3 | Short |

| H4 | Couple with 1 child | P4, 40’s, Woman | Software developer | 13 | None |

| H5 | Father with 1 child | P5, 60’s, Man | Retired | 100+ | Long |

| H6 | Living alone | P6, 30’s, Man | Recruiter | 4 | None |

| H7 | Flatmates (3 members) | P7, 20’s, Man | MA student computer science | 6 | Long |

| H8 | Living alone | P8, 20’s, Man | MA student law | 0 | Short |

| H9 | Flatmates (3 members) | P9, 30’s, Woman | PhD student biological and behavioural science |

0 | Medium |

| H10* | Living alone | P10, 80’s, Woman | Retired | 30 | Long |

| H11 | Flatmates (3 members) | P11, 20’s, Woman | PhD student molecular science | 1 | Medium |

| H12 | Flatmates (2 members) | P12, 20’s, Woman | PhD student computer science | 1 | None |

| H13* | Living alone | P13, 30’s, Man | MA student filmmaking | 10 | Long |

3.5 Data Collection

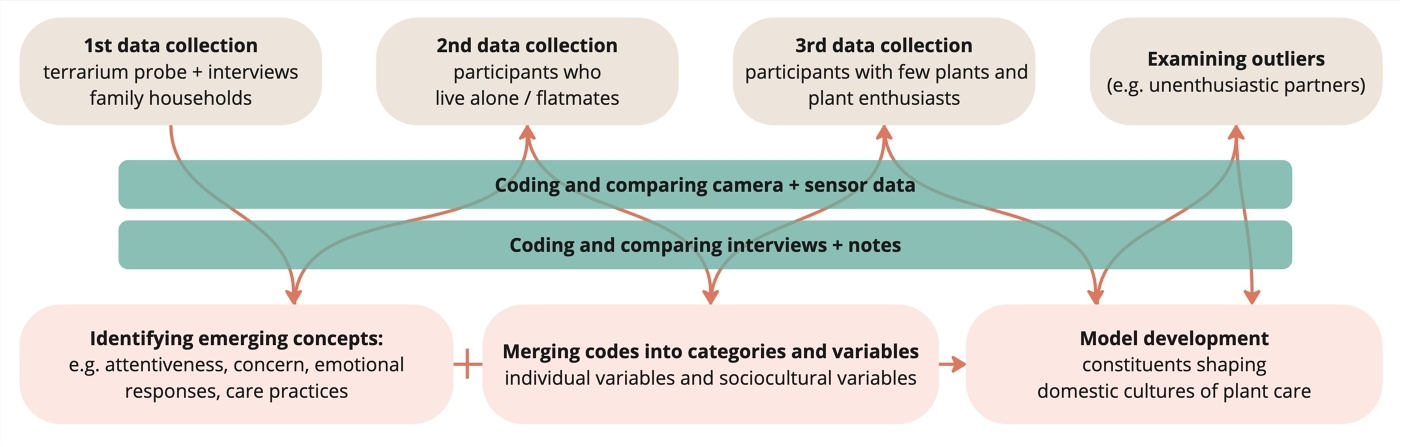

To allow for cycling between data collection, coding, and theorising, we constructed four terrarium probes and collected data in three waves, each time capturing 3-4 households. We started the first wave by sampling family households. Wave two sampled participants who lived alone or with flatmates as a useful comparison group. The third wave included two individuals who own very few plants and two additional interview-only participants with long plant-care experience.

We collected and compared three main types of data:

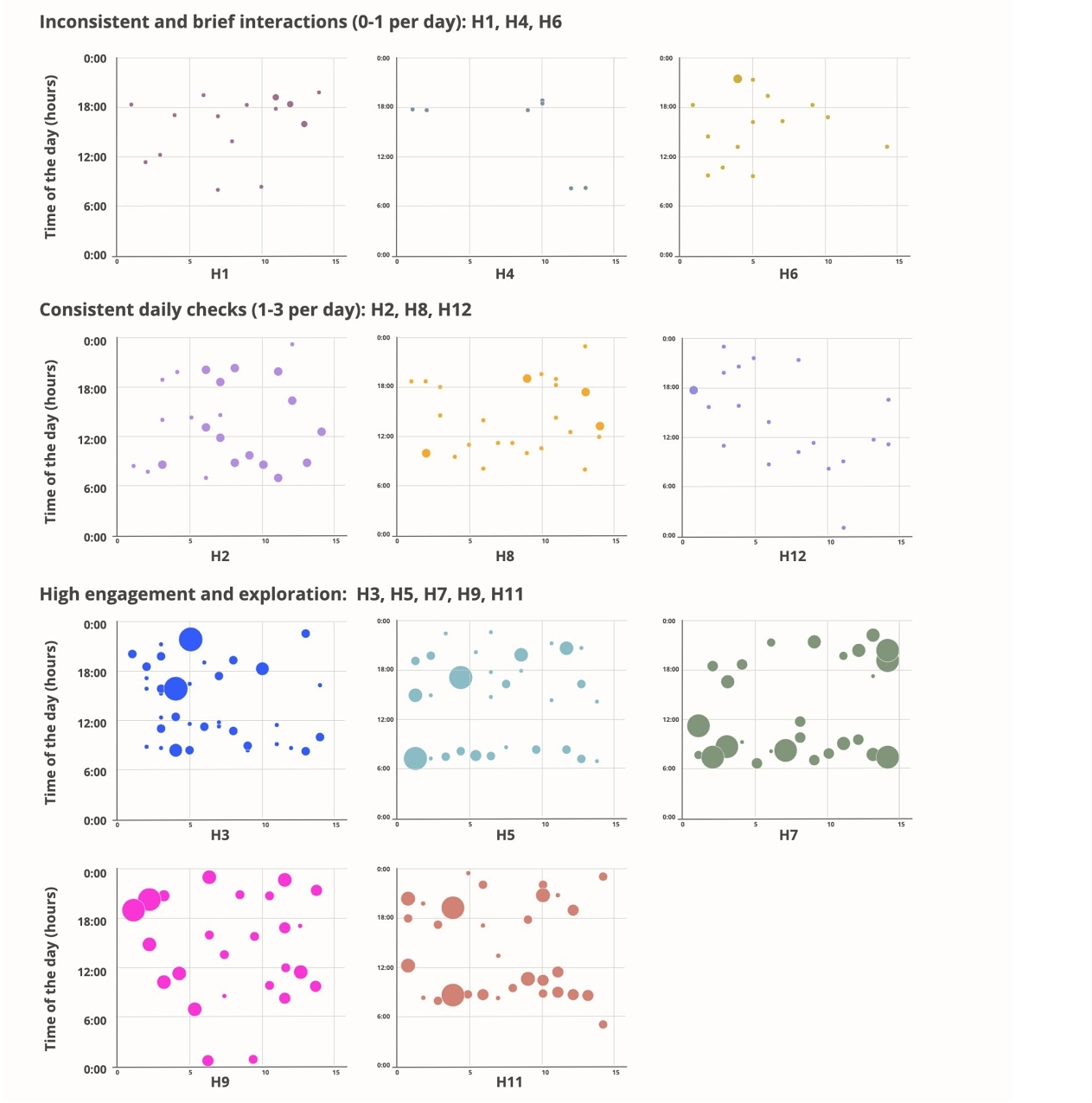

a) Recordings of participants’ interactions with the terrarium: Before each interview, we visually reviewed video interaction recordings and transcribed them as log entries in MS Excel, capturing interaction time, duration, type of interaction (watering, touch, speech), who interacted, and whether they did so individually or with others. Frequency and length of these interactions indicated participants’ engagement with the terrarium (table 2). We also visually plotted this log data to see differences (figure 8). In total, we collected and analysed 436 video recordings from the terarria intervention probes.

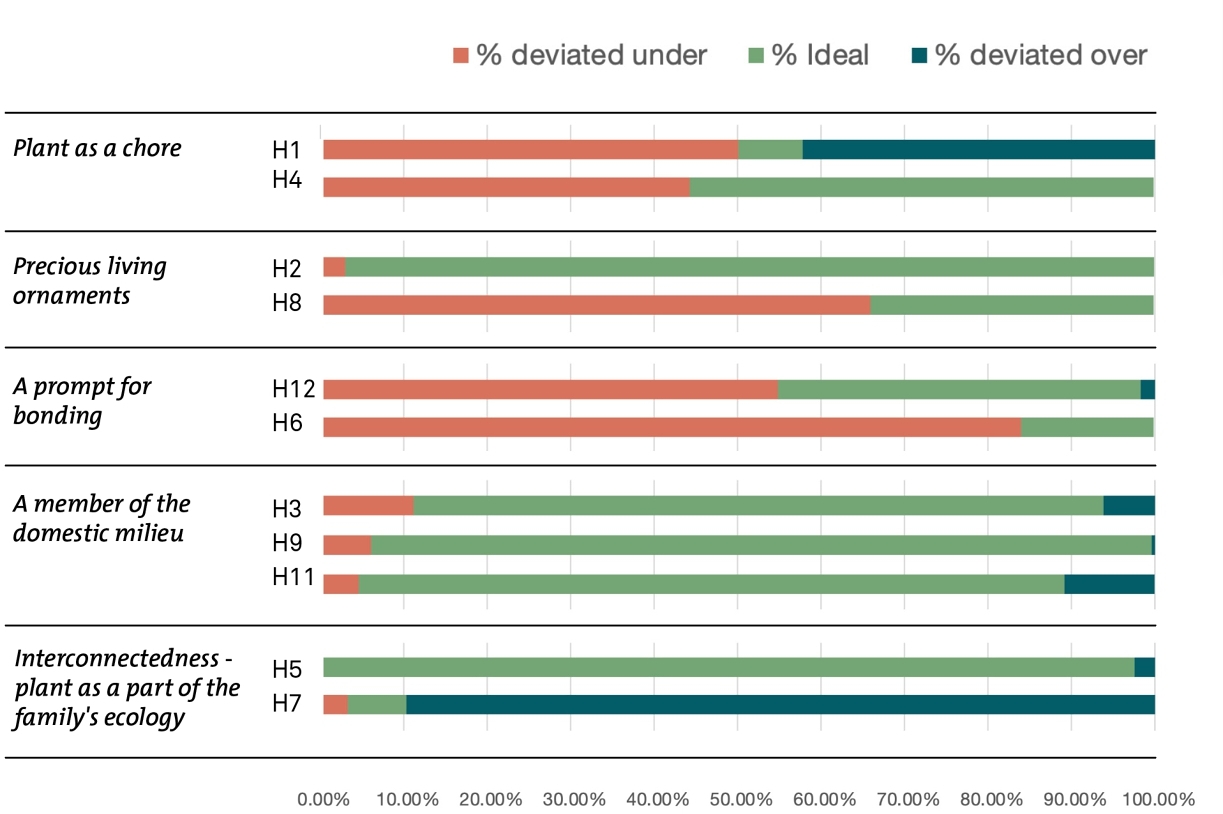

b) Moss's welfare status: We assessed the moss's welfare by analysing sensor-generated moisture and temperature data, comparing these values to the optimal conditions (see hygrometer readings data in supporting materials), coding the proportion of time that humidity was under or over the ideal range (75-96.5%) (fig. 9). Additionally, we reviewed daily photos and a time-lapse video (see supplementary materials) to track changes in the moss's colour and wilting over the two-week period, and whether the terrarium was placed in suitable lighting conditions or watered properly (indicated by changes in the leaves’ colour to red, yellow or brown).

c) Interviews with lead participants, household members and researcher's memos: Household visits typically took place 2-7 days after the two-week terrarium hosting period and lasted approximately 45 minutes, including recorded interviews lasting 11–35 minutes, for a total of 51,760 words of transcripts, done using the f4 software.2. Some household members joined the lead participants for the conversation or gave an interview separately. Additionally, we kept field notes during the installation and retrieval of terraria, along with comparative notes and memos across households.

Informed by a prior review and analysis of their terrarium recordings, interview prompts focused on participants’ experience with the moss terrarium, what they observed or noticed and decisions they made while taking care of it, as well as views and attitudes towards houseplants, their understanding of plant needs, perceived accountability, and attachment to their plants. We added and refined questions to explore recurring themes and emerging questions such as family and social circle involvement in plant care, childhood memories, and cultural influences (see interview guide in the supplementary material).

| Participant Household Group |

Total Interactions |

Avg Interactions per day |

Avg Length/day (sec) | Min Length (sec) | Max Length (sec) | Std Dev (sec) |

Total Length (sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 20 | 1.4 | 16.9 | 8.0 | 31.0 | 7.0 | 236 |

| H2 | 26 | 1.9 | 32.0 | 9.0 | 33.0 | 7.0 | 448 |

| H3 | 41 | 2.9 | 68.8 | 9.0 | 134.0 | 27.6 | 963 |

| H4 | 8 | 0.6 | 5.6 | 9.0 | 13.0 | 1.5 | 79 |

| H5 | 32 | 2.3 | 82.3 | 5.0 | 377.0 | 69.0 | 1,152 |

| H6 | 14 | 1.0 | 9.7 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 1.9 | 136 |

| H7 | 28 | 2.0 | 171.1 | 9.0 | 293.0 | 80.0 | 2,395 |

| H8 | 25 | 1.8 | 19.6 | 7.0 | 30.0 | 5.5 | 275 |

| H9 | 27 | 1.9 | 116.7 | 9.0 | 242.0 | 49.9 | 1,634 |

| H11 | 33 | 2.4 | 96.8 | 8.0 | 172.0 | 38.5 | 1,355 |

| H12 | 19 | 1.4 | 12.6 | 4.0 | 20.0 | 2.8 | 177 |

| Total | 24.8 (avg) | 1.7 | 57.4 | 4.0 | 377.0 | 47.7 | 804.5 (avg) |

3.6 Data Analysis

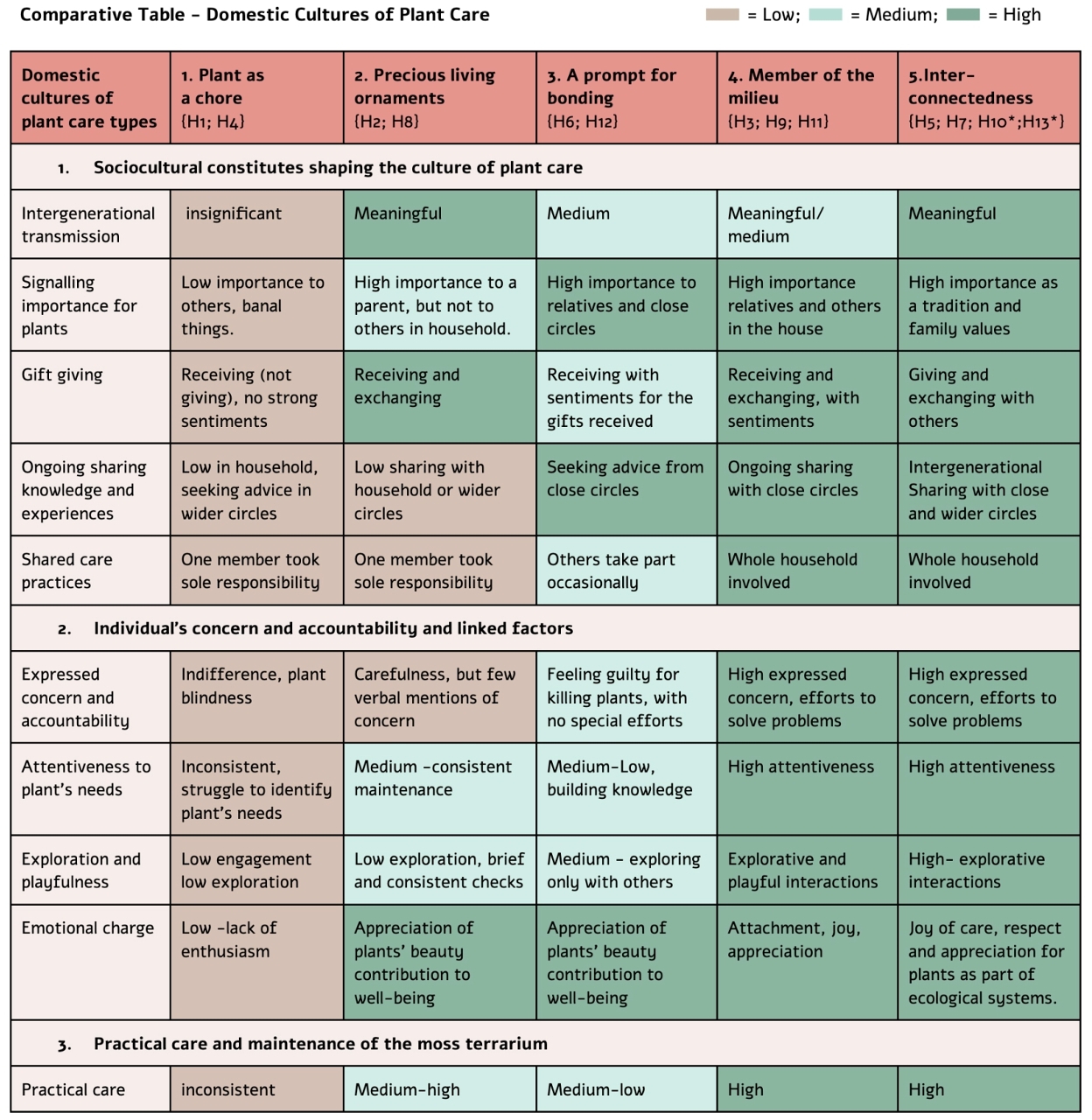

We followed qualitative data analysis by Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña [58], which employs common ‘first cycle’ and ‘second cycle’ coding of data to develop initial concepts and more integrated categories and variables, followed by more inductive model development through various forms of compressed data display (see analysis process in figure 5). Two main data display formats are matrix displays (tables comparing cases or other units of analysis by chosen parameters) and cross-case causal networks (boxes and arrows modelling causal processes). In our case, this culminated in the development of our explanatory causal network model (figure 6) and the matrix of five types of domestic cultures of plant care (figure 7).

Our analysis began with the first and second authors reviewing camera/sensor data from five initial households (all families), making preliminary annotations and first cycle open codes. The first author then coded interview transcripts and field notes line by line, and compared data from the probe's sensors with verbal quotations from interviews, memoing and coding noteworthy relations. All three authors then discussed open codes and memos to develop unifying concepts, supported by diagrammatic theorising on digital whiteboards. Early codes included awareness of plant needs, expressions of concern, emotional responses ranging from joy to indifference, mentions of childhood memories, and conceptualisations of houseplants (e.g., as resources, aesthetic objects, or companions).

After collecting and coding data from a second wave of households (focusing on those living alone), we constructed a matrix display of cases (=households) and merged codes into categories or variables. We iteratively revisited transcripts and interaction recordings, adding and refining categories and variables such as exploration and playfulness, attentiveness, accountability, gift-giving, shared care, and sharing experiences with others (see full coding tree and code counts in supplementary material).

In the third data collection and coding wave, we added two more households, along with two interview-only participants who had extensive experience with plant care, and ran additional interviews with participants’ partners claiming “no interest in plants” to capture diverse viewpoints. Beyond refining existing categories and variables, we now switched theorising from a case view to cross-case causal modelling, mapping how different constituents of domestic cultures of care impact each other and different forms of expression of concern and accountability. We then reconnected this model to our case matrix to identify different types of cultures of plant care, examining unaccounted ‘outlier’ cases and exploring alternative explanations including social desirability biases and participants’ self-presentation strategies, until our models and data reached thematic saturation for us [69].

See Supplementary Material for final interview guide, anonymised transcripts, coding tree, picture stills, sensor read-outs and the instructions participants received.

4 Findings

In our analysis, we sought to uncover factors shaping plant care attitudes and practices, to inform design interventions that foster deeper concern for plants. We found that individual concern and accountability are influenced by broader social, and familial plant care ecology which we define as domestic culture of plant care. These cultures are shaped by a combination of constituents including: intergenerational transmission, signalling importance to plant care, sharing of knowledge and experiences, shared care practices, and gift-giving (Fig. 6).

In the context of this study, “concern” means valuing a plant's welfare, coupled with a sense of accountability that drives both worry when challenges arise and motivation to resolve them. Observations and interviews revealed that participants showing higher concern and accountability maintained the moss terrarium more frequently and consistently, engaged in exploratory and playful interactions, showed notable attentiveness to the moss's needs, and voiced emotional responses such as joy, attachment, improved well-being, or nostalgic memories tied to plant care. Conversely, participants who viewed plants as burdensome chores or aesthetic objects indicated lower concern and exhibited reduced engagement with the terrarium.

A key insight was that social connections and family networks affect these attitudes. Participants frequently referenced the importance of plants within their close social circles, often rooted in intergenerational transmission – meaning the process by which behaviours and ideas are passed down through generations and early life experiences at home [53]. Attitudes were also shaped by ongoing domestic social dynamics, such as sharing knowledge or signalling the importance of plant care to other household members – either implicitly by taking active care and tending plants or explicitly by discussing values or giving plants as gifts with sentimental meaning. In households that emphasised shared care or discussion about the terrarium, engagement with the terrarium was more frequent, playful, and attentive, driving stronger concern and creative problem-solving.

We also observed that family households varied in how they involved children in plant care, showing different ways plant care knowledge and practices are—or aren't—passed down. From these observations, we identified five distinct cultures of plant care: (a) plant as a chore, (b) precious living ornaments, (c) a prompt for bonding, (d) a member of the domestic milieu, and (e) interconnectedness—plant as part of the family's ecology.

In the following sections, we show how the concepts in our model materialise in each of the five cultures, and how each culture influences individual attitudes and actions toward the terrarium, underscoring the impact of social factors - see comparative table (figure 7). Since unpacking and evidencing every code would exceed the scope of this paper, we direct readers to our coding tree (in the supplementary material) with instance counts and data excerpts.

4.1 Plant as a chore

“It's going to be in the corner. It's going to look nice (.) if it lives, like, if it thrives and it grows - Okay. And if it dies - fine" [H1 - father].

This culture represents households and participants [H1, H4] who discussed houseplants mainly as commodities or aesthetic objects that require maintenance, similar to mundane chores of cleaning the house. Framing houseplants as another type of routine chore is familiar and prevalent among modern societies where plant care guidebooks carry the name "How NOT to Kill your Houseplants"[62].

This approach was also adopted towards the moss terrarium in these households: "It's quite a distraction in a way (...) but it's also just part of the day (.) You load the dishwasher - you water the moss" [P4]. It correlated with comparatively low concern and accountability, demonstrated by minimal and inconsistent interaction with the terrarium, instances of missed watering days, overall low attentiveness to the moss's condition with little to no exploration or touch of the moss to assess its needs, like moisture levels or adjusting its position to avoid direct sunlight.

In the lively family at H1, both parents described a weak intergenerational transmission of plant-care practices or values. The mother (lead participant P1), new to plant care, recalled a childhood home without houseplants or meaningful family interest in plants as gifts. She appreciated plants for their aesthetics, noting “they (.) make the house look more lively (.) I am thinking about decorating the walls, so I should just put a plant there. It replaces art in some way”. But she referred to them as commodities that she constantly replaces, indicating low emotional charge in the context of plant care: "you spend like so much money on these plants and some of them die quite quickly"[P1]. Her partner expressed similar indifference and low accountability towards plant's welfare: “I didn't have particularly strong thoughts about it. Or emotions towards it (.) it was, you know, just another thing” [H1 father].

The family initially agreed to share responsibility for the moss terrarium, though the adults mostly viewed it as a chore and had little interaction with it, signalling low importance. The younger child proudly asserted taking on more care than his parents, remarking, "Mom, all you did was remind me to water it.” He showed keen interest in discussions about houseplants and the terrarium, but his curiosity received little support from family members. The older brother offered some school-taught knowledge but remained disengaged, saying, "It looks cool, but none of my friends would be interested in that.” This further illustrates the importance of social influence in fostering plant care, and the low motivation to share experiences among these household members.

In practice, the younger child handled most of the watering, occasionally with his mother present. However, inconsistent watering eventually led to flooding the terrarium with tap water (harmful to moss), a mistake his mother had also made with her other plants – despite the researcher and shared guidance material advising against it on setup. Compared to other families we observed, this example underscores that while child curiosity offers an opportunity to pass down plant care practices, it needs guidance from more knowledgeable others to be made productive.

In Household H4, the mother (lead participant P4) expressed a similar lack of enthusiasm for plant care, stating, “I don't have any passion for gardening or plants”. She attributed this to her upbringing, noting, “I grew up in the desert (.) with no houseplants. I have no knowledge.” [P4]. Despite this attitude, the family keeps several plants at home, although P4 admitted to low concern for their welfare, explaining, “We are just very busy and they are shrivelling. (...) some of them come with manuals (.) and some I kill very quickly.”

P4 neither shared responsibility for the terrarium with her partner—whom she described as the primary caretaker of their other plants—nor actively involved her son. However, recordings revealed that her son occasionally interacted with the terrarium, rearranging moss and pebbles, playing, and even watering it a couple of times without his parents’ awareness. P4 was surprised to learn about her son's interest and later acknowledged the missed opportunity to explore the terrarium more herself and with him. Overall, the lack of sharing knowledge, experiences and care practices in this household limited interaction and exploration with the terrarium and led to the moss wilting (see Fig. 2).

4.2 Precious living ornaments

“The plants are part of the house, part of the furniture (.) part of our identity” [H2 - lead participant P2]

This culture of care was identified at H2 and H8, and involved viewing plant care as akin to preserving heirlooms or valuable ornaments, considering them as fundamentally interwoven with the home's identity. These households show high intergenerational transmission of plant appreciation from their childhood home and parents, but low active sharing of knowledge, experiences and care responsibilities with others in current close circles, eventually demonstrated as a very pragmatic approach to care and commitment to maintaining the plants successfully with little exploration.

P2, who has cared for plants for over 15 years, highlighted the aesthetic value of houseplants: “They are my precious. I love green; it makes me happy”, P8 had a similar perspective saying "It just feels nice to have something green around you. Something which is alive (.) But for the atmosphere (.) and (care for plants) it's really just a muscle". Both demonstrated accountability towards the terrarium, adhering closely to the guidelines provided by the researcher and displaying consistent care. As P2 noted: “I have dedication. I promise to take care of it. So I took care of it, and I was responsible enough to give it water twice a day”. However, their interactions with the terrarium were quite brief and lacked exploration. P2 explained the low interaction with the low decorative value of the terrarium: “I can't really enjoy it like the other greens. It's very flat, thin and small.” The lack of exploration limited opportunities to notice changes or creatively solve problems, particularly during hot weather which challenged conditions at H8.

Both P2 and P8 recounted strong appreciation for plants, rooted in their mothers’ dedication to maintaining a house full of greenery. However, P2 noted she was not involved in their care as a child and only learned to admire their beauty. This appreciation is demonstrated by exchanging plant gifts with others, but it was not shared with others from their close circles. Like her mother, P2 manages all houseplant care independently. When her family received the terrarium, she discouraged her children from interacting with it, saying, “I told the kids to be careful not to touch it (...) nobody paid attention to it other than me”. She assumed her children were uninterested, which was confirmed as no one else approached the terrarium. Her primary concern was to maintain its condition for the researcher, showing little curiosity or excitement about caring for a plant she found aesthetically unappealing and saw no reason to share her plant care knowledge with her family. Consequently, other family members avoided responsibility for the terrarium, expressing low confidence. P2’s partner voiced his reluctance after reading the consent forms, stating, “I don't mind the privacy issues; I just want to be sure I'm not committed to keeping the plant alive!”.

Despite P2’s strong dedication to her plants, the absence of communal care and knowledge sharing limited her family's engagement and exploration in plant care, and as she admitted, she can not trust others to take care of the plants when she is away. However, her mother's emphasis on plant care likely influenced P2’s appreciation for plants, which may be passed on to her children as they grow.

4.3 A prompt for bonding

“I send pictures of my succulent to my grandmas (...) they teach me how to care for it.” [P12]

In this culture, houseplants are seen as points of interest to spark conversation, prompt the exchange of stories, photos and experiences among close ones. This culture represents P6 and P12 who recently begun caring for plants, inspired by other's interest in plants. They are in the stage of building their plant care knowledge and practice by reaching out to their relatives for guidance, creating a new opportunity for connection, potentially enjoyable on both sides. This practice—much like cooking or crafts— both originated from and facilitated social and generational bonding.

Opposite the the previous culture, in this case the ongoing sharing of knowledge and experiences, the importance to other close ones and the sentiments carried with received gifts are dominant factors, while childhood memories were not as meaningful. P6 recounted that, although his parents were enthusiastic gardeners who opened their impressive garden to the public, he had always avoided gardening himself admitting past failures with a sense of guilt: “I've killed everything I've ever had before (..) I looked after my sister's plant once she moved to Canada and she gave me her favourite houseplant and I killed it in a month”. However, when his girlfriend gave him a plant as a gift after long hospitalisation, he started developing a shared interest with his parents as well, noting, “They were very happy when they found out I was doing stuff (with plants)”.

Although P6 and P12 had only brief, somewhat limited interactions with the terrarium, their engagement grew when more experienced individuals—like P6’s girlfriend or P12’s flatmate—got involved. Both participants showed greater enthusiasm when discussing shared plant care with friends or family, suggesting social support and collaboration are strong motivators. This could be viewed as a stage of building plant-care confidence, bolstered by others’ involvement.

4.4 Plant as a member of the domestic milieu

“We decided it (the terrarium) would be a girl because we don't have many girls at our home” [P3 lead participant (mother)]

In this plant care culture, the terrarium (or other plants) is viewed as members of the household's milieu akin to having pets. P3’s comment above is especially interesting- showing how household H3 explicitly (mentally) place the plant into their social network. This approach was also evident among other participants P9, and P11 (who live alone). They all showed high concern and engagement—spending extended time with the moss terrarium, and documenting their experiences through personally taken photos and videos, and sharing these with friends and family. As P9 explained, “I have a friend who also likes plants... I told my girlfriend and three friends from Brazil and sent them photos saying, ‘Look, I adopted a terrarium.’”

The practiced care and expressions of households represented by this culture were coded with high values for almost all factors. Members acknowledged plants’ importance to their close social circles, discussed exchanging plants as gifts and how this created sentiments, and most notably, emphasised and mentioned repeatedly their sharing of experiences, exploration and care responsibilities with their friends, siblings and parents.

Far from being a routine chore, plant care was a meaningful activity for them, often tied to emotional expressions, the youngest child at H3 suggested: “Maybe it's like a journey of making them grow". P9 recalled missing the plants she left in her hometown because “I really like to have this time to take care of them.” Participants likened plants to pets and emphasised the positive effect of nurturing a “living being” in their environment—especially if owning an actual pet wasn't feasible. P11 noted, “I've always liked having something living in my room... It makes me feel better... I'm taking care of it, and it's living. It feels good.” She fondly recalled the excitement of observing her family's balcony plants at home, especially the rare, sweetly scented night-blooming flower: “It smells really good. It's a really enjoyable experience.”

Another notable aspect in these households was the exploratory and playful nature of their interactions, and their creative plant care methods, going beyond the provided instructions. For instance, they sprayed rocks to mimic distilled water [P9] and frequently adjusted the terrarium's composition [P9, P11]. In family H3, with three children and dedicated parents, all family members frequently interacted with the terrarium, individually or together: observing it, experimenting with different spraying methods, reacting to its smell, and sharing observations. The family even named the moss “Kate Moss,” with the mother describing the terrarium as both “a wonderful toy and “a kind of a weird animal”, and the kids asked if they could keep “her” after the study.

The children at H3 discussed how they explored the terrarium, looking at it when bored, studying its composition and using different humidifier tools. One of them explained his interest in the terrarium: “we can actually do stuff with it, like spray it. Um, put the mist on, which is quite cool. So it's nice because you can actually take care of it actively", his brother added: “my brothers and I had different techniques for watering it. My technique (.) was watering the corners first and (then) the middle (..) and I saw how it turns greener".

Although the parents did not consider themselves experienced plant carers -the father admitted in the interview that “I don't find taking care of plants as a super important part of my day to day"-, their attitude toward their own houseplants and the terrarium showed high concern as well as curiosity. They read about the moss and made the care process accessible and enjoyable for everyone in the household, even placing the terrarium in the children's playroom. When asked about the other houseplants in the house, one of the kids expressed their importance, saying that without them, the house “wouldn't be so special I think (.) if we won't have lost plants (.) we don't have any, like, how can I say ’Mother Nature’ in our house".

H3 case shows how communal shared care for plants and active involvement of the family members can enhance exploration, joy of plant care and confidence in recognising plant needs among children and adults.

4.5 Interconnectedness - plant as a part of the family's ecology

“It's breathing, living with us. (...) I grow it near me, so it will grow with me.” [P13]

In this culture of care, intergenerational values and respect for nature were especially prominent, supported by a strong family tradition of gardening and nurturing plants. H5, P7, P10, and P13, who represent this culture, all described formative childhood experiences actively gardening with parents and close relatives. They also emphasised giving plants to others and sharing plant care knowledge, eager to pass on their enthusiasm and experience. They described their tradition of living alongside and nurturing plants as central to home life, highlighting the interconnectedness between people and plants, as P5 (lead participant, father) explained: “In India, usually the family stays along with plants and animals. We respect animals, and we respect plants also... We know plants have a life, so they shouldn't be bothered... we nurture them and they support us by absorbing CO2” further comparing caring for plants to nurturing a child, and sharing: “Some plants should be there to take care of; otherwise, you feel some emptiness... They say if you touch a plant, it will grow faster... we touch it, and we feel good.”

Family H5 consisted of a grown daughter and her visiting father, who owns hundreds of plants back in India. At their home, plant care is a shared family responsibility. As the daughter explained, “It's like a family house. My aunts usually take care of all the plants, and now that Dad is retired, he has joined the gardening.” The father and daughter tended to the terrarium with dedication and expertise, adding a cap to retain moisture and routinely checking it during meals—deciding if it needed “food or drink”. Although the daughter admitted she wasn't as enthusiastic as her father, she demonstrated confidence in plant care. Video recordings further showed that the father's culture of care encouraged her to engage with the terrarium independently.

P7 traced his passion and knowledge of plants back to childhood experiences helping his father in the garden, including attempts to save a diseased tree. He showed strong dedication to the terrarium, collecting rainwater for it and repositioning it multiple times a day to avoid direct sunlight. He noted that sharing space with plants significantly improves his well-being: “I was happy to see a lot of plants because it's like (.) I can feel more life inside the space.”

Other participants with lifelong experience in plant care: P10, who was raised in a rural area in the UK before moving to the city, and P13, who relocated from South Asia, expressed similar attitudes, and emphasised the joy and benefits of nurturing plants. P13 shared, “I would go with her (grandmother) and smell seeds and logs (.) dig the soil, smell of earth (.) and then you make beds for certain root plants like radishes (...) then three days later you see the plants coming out (.) it is giving us some sort of relaxation (.) that is a feeling of an achievement.”

P10 shared “I've always loved them. I've grown up loving them, influenced by my parents. (...) I love seeing them grow, the colours, the scent (.) aesthetically speaking, I think they are good companions (...) and I'm lost without them (.) as children, we had our own little garden (.) my parents taught us how to garden (...) It was very much part of my life. And we were self-supporting, you know, we never bought vegetables, we grew everything, (.) we grew a lot of fruit, which we picked and cooked, we made jam (.) my life was really very centred around the garden, and nothing went to waste.”

These participants maintain a cultural and family tradition of viewing plants as integral to their domestic ecology and seeing them as interconnected living companions. Beyond simply expressing love for plants (as seen in the previous culture), they describe relying on the plants’ vitality and closeness just as much as they enjoy caring for them.

5 Discussion

Our findings show that houseplant care spans a spectrum of forms— from framing them as mere decorations or chores to regarding them as living companions worthy of respect. From the terrarium probe, we learned that stronger concern and accountability correlated with attentiveness, exploration, and playfulness—individual behaviors fostering emotional engagement and problem-solving. Notably, these behaviors didn't necessarily align with owning many plants or having extensive experience; rather, they were boosted by social factors, particularly when novices received guidance from more knowledgeable peers. In contrast, when just one household member managed the terrarium in isolation, both engagement and consistency waned.

Thus, we observed how sociocultural influences shape attitudes toward houseplants. For instance, seeing a plant as a living being with moral standing often emerged alongside shared care and the joy of involving friends and family—through gift-giving, intergenerational learning, and peer knowledge exchange. Such communal involvement encouraged exploration, enjoyment, and greater appreciation for the plant's life.

In design terms, these findings highlight the importance of social context beyond the plant-individual, short-term interactions or interventions outside the domestic context. Prior HPI work has studied social contexts, especially urban and other farming or gardening communities [54, 64, 66]. However, their research attention and interventions then chiefly trace how to afford multi-species social connections and collectives between humans and plants (see also, e.g., [36]). The novel dimension our findings bring is a focus on human-human social relations as a pervasive, already-existing shaping force of plant care.

In the following, we tease out ramifications of our findings for design interventions and HPI research, centred on existing theories of change in HPI, design opportunities around fostering a culture of sharing plant care knowledge, the role of technology, and thing ethnography as a method.

5.1 Houseplants, Communal Care, and HPI Theories of Change

HPI work variously instrumentally positions HPI as a direct contributor to wellbeing or pro-environmental behavioural intervention. In our study, many participants viewed houseplants as a way to bring nature indoors, describing them as "having the outdoors inside" [P2] and noting how they make their homes feel more alive. The joy of observing plant growth or new blooms reinforced the felt connection between domestic spaces and broader living environments. However, few participants explicitly linked this experience or their houseplant care to concern for the larger environment. This contradicts prior HPI work suggesting that interacting with and caring for individual plants may foster broader environmental care [54].

Not only did caring for a new houseplant not appear to translate into heightened environmental concern: introducing the moss terrarium also did little to overcome a prior lack of accountability toward houseplants themselves, apart from social desirability prompting some participants to appear “good” in the study. That said, we found that the terrarium did spark spontaneous curiosity and shared exploration that led both younger and older participants to engage with family and social networks—a pattern underscoring the role of social dynamics in developing a culture of care and concern for plants. Along these lines, a two-week observation period may simply have been too short to develop houseplant or wider environmental concern. If so, this suggests at least a need to theorise and test what intensity and duration of enculturation in houseplant care is needed to change attitudes and behaviours.

Another upshot of our study is that HPI and other HCI interventions in domestic environments can potentially foster meaningful connections within close social circles — such as between parents and children, neighbours, flatmates, or even distant relatives. Houseplant care, a simple and accessible activity, can serve as common ground for multi-generational collaboration. While experienced family or community members can contribute valuable tacit knowledge, younger or less experienced members bring curiosity and enthusiasm. In settings where such interactions do not happen organically or where the culture of care and communication is weak, HCI interventions can focus on augmenting interest, accessible knowledge, or accessible social networks.

In short, our findings highlight the need for an additional perspective on theories of change in HPI—one that emphasises social factors and more longitudinal social processes to shape attitudes. Traditional HCI theories often focus on changing individual behaviour [84] or short-term, solutionist approaches [8]; our study advocates for a more holistic approach that designs for and with communal experiences, patiently cultivating a culture of care within families or close social circles.

5.2 Opportunities for Developing Cultures of Care in the Domestic Milieu

In some anthropological approaches, things are seen as person-like, as they are positioned in a web of social relations [28]. Our findings suggest that a houseplant is similarly embedded in a domestic milieu where plant care cultures emerge through key social interactions. This directs us toward new and different directions for designing interventions to reshape connections and perceptions of plant's moral status. At least two directions come readily to mind, informed by anthropology and the already spontaneously occurring practices of our participants: gift giving and intergenerational transmission.

Gift giving: Anthropologist Marcel Mauss described how a gift carries part of its giver [57]; thus, gifting a houseplant infuses it with emotional weight and can heighten accountability for its care. Plants inherited or kept long-term become heirlooms, further strengthening these bonds. Designing interactions that highlight a living plant as a growing gift can lean into this – and is something we already encountered among our participants.

Peer learning and intergenerational transmission of values and practice: Participants explored the terrarium more enthusiastically when doing so with others, whether in person or remotely, prompting shared discoveries and collective knowledge. This impact of close others on similar behaviours and perceptions is acknowledged in the wider context of pro-environmental behaviour research [13]. Design can again lean into this by offering supportive tools and connections for collaborative plant exploration and care, peer learning, intergenerational connections, and creating opportunities for individuals to signal the importance they place on plant care. By integrating such social and collaborative dimensions into human–plant interactions, design can enhance a plant's presence in the home and spark dialogue about its role and value within the domestic space. Designing experiences that cultivate joyful care, promote exploration, and invite the sharing of impressions and concerns among household members can foster deeper appreciation. Over time, this can lead to greater attentiveness, a sense of accountability, and a feeling of interconnectedness, as the social circle develops new routines, norms, and values around plant care practices.

5.3 The Role of Technology in HPI

“Can I see my moss terrarium's selfies?” one participant asked jokingly after the interview, personifying the terrarium as if it were an active subject. Our sensor-equipped moss terrarium was originally designed to gather data on participants’ daily care practices and attitudes, not technologically remediate the human-plant relation.

However, the cameras and sensors also shaped how participants perceived the terrarium. In several cases, household members were more curious about the technology than about the moss itself. This observation aligns with prior research on social media sharing around houseplants [51], suggesting both a design opportunity—where technology can help bridge the gap between people and plants—and a potential risk, if technology ends up distracting from the plants, shifting focus towards a virtual space.

Based on our domestic care ecology model, technology should prioritise enhancing social dynamics and shared exploration in plant care, rather than objectifying plants as mere inputs or outputs, as often seen in HPI [54]. This can involve standard forms of collaborative and networking technologies – including social media –, but also display or signal augmentation technologies more common in HPI, provided these contribute to framing and viewing houseplants as part or mediators of the wider social mesh of care.

5.4 Living Thing Ethnographies

Using the living moss terrarium as a thing ethnography probe alongside interviews enabled us to uncover rich, multi-layered insights into plant care practices. As hoped, it revealed tensions between what participants said about their plants and how they practically interacted with the moss terrarium. These comparisons surfaced underlying socio-cultural concepts—such as the plant's perceived moral status—that not only shaped care practices but also influenced how people understood and talked about plant care. It also surfaced kinds of interactions (pet-like engagement) and subtle differences in interaction (e.g., between caring alone versus with others) that would likely have remained invisible through traditional methods. These are solid, ‘standard-issue’ social research reasons for using living thing ethnographies in particularly mundane, routinised HPI.

Is there an additional more-than-human surplus? Some more-than-human methods, such as alien phenomenology, try to materialise “what it's like to be a thing” [6]. By comparison, our living thing ethnography remained content with a quite gentle and empiricist recentering: instead of speculative role-play or metaphorising, we banked on the human-visible colourisation and leaf shapes of moss to trace its wellbeing, and ‘merely’ captured interaction from its perspective and point in space and time. Still, we think this sufficed to reveal and recentre something important – that houseplants are a node within a network of plant-human relations and interactions. This would be hard to trace if the unit of analysis and data collection is the individual human participant. Especially when our attention shifts to tracing social relations and networks of multi-species agents across time and space, living thing ethnographies could offer a highly useful method for tracing.

5.5 Limitations

Moss is an uncommon houseplant—unfamiliar to most participants and differing aesthetically from typical flowering or vascular plants—which may affect the generalisability of our findings. Participants were asked to compare the moss to their other plants, and while some noted its uniqueness, their underlying attitudes toward care and moral framing of plants and the moss remained consistent. For instance, one participant described the moss as “too small to enjoy,” yet still expressed a protective, pragmatic care similar to that shown toward her other plants. Others who engaged playfully with the moss also tended to personify their other houseplants during the interview or when discussing them with others at their household. Although the moss was newly introduced, participants attributed to it a moral status similar to that of their other houseplants. The terrarium helped reframe moss—which is typically overlooked in outdoor settings—as a legitimate indoor plant with comparable moral value. While some of the curiosity and engagement observed may have been influenced by the moss's novelty, it is unclear whether similar responses would occur with more familiar plants. Nonetheless, the key socio-cultural dynamics identified—central to our findings—emerged consistently across both the moss and participants’ other houseplants.

We noted signs of social desirability [49], where participants adopted “good participant” or “evaluation-apprehensive participant” roles [83]. For instance, one participant worried that leaving the terrarium unattended might mean their interactions went unrecorded, implying they might have been more relaxed without the camera. In three households, participants increased their interaction with the terrarium toward the end of the study, perhaps knowing they would soon return it. Meanwhile, some participants claimed in interviews that they tended the terrarium more often than the recordings indicated, suggesting they were not always conscious of the camera. To address these effects, we asked about camera awareness during interviews and compared observed and sensor data with participants’ statements. This triangulation provided a more nuanced understanding of engagement. Crucially, our central insight regarding social factors appears largely unaffected by these biases, as participants directed their social desirability concerns toward their individual plant care practices rather than their social interactions.

Shorter attention spans among younger participants, language barriers, and limited plant care experience resulted in less detailed interviews for some participants, potentially limiting the depth of our codes. This issue is especially relevant since this group represents a likely target audience for future plant care interventions. That said, even these short interviews informed and were thus congruent with our model.

Other limitations arose from technical and ethical considerations. Some interactions may have gone undetected due to a limited motion detection range. Recordings were capped at 9 seconds unless interactions were longer, with the system pausing every 20–25 seconds to conserve battery life and reduce the risk of capturing sensitive data. Thus, some qualitative details may have been missed. The hygrometer readings had similar limitations as participants occasionally moved the sensor, affecting consistency. We addressed these issues by comparing readings with visual data and assessing the terrarium during collection.

A final limitation concerns our geographically and to some extent, socio-culturally homogeneous sample. The UK city we conducted our study in houses first-generation immigrants who were brought up in a wide variety of cultures and nations, which is reflected in the cultural diversity of our sample and made explicit by participants calling back to their childhood upbringing in, e.g., India. That said, we did not sample across different geographical locales embedded in local climates, infrastructures, and cultures, and due to our recruitment strategy, our sample skews educated and middle-class by local standards. Thus, our data is arguably insensitive to the potential impact of these wider contextual and demographic factors.

5.6 Future work

We see compelling opportunities for future research to expand understandings of care for plants through deeper engagement with social, intergenerational, and domestic contexts. In particular, we propose more in-situ interventions with individuals and communities who may not currently express a strong interest in plants, to explore how communal caregiving, playful shared interactions, and the formation of caring networks might shift attitudes and foster new domestic cultures of plant care. These explorations could reveal how plants become embedded as meaningful actors within the home, especially in environments where such relationships do not yet exist. We also envision designing for intergenerational engagement, where storytelling, peer learning, and shared curiosity create bridges between people and the plants they care for, reinforcing long-term attachment.

In addition, we are interested in how everyday care practices— such as tending to a mini terrarium—might offer a gentle but meaningful response to the problem described as the “Extinction of Experience” the degradation of everyday experiences with nature [71, 72]; Design may address this by reintroducing sensory and affective connections to the natural world through routine domestic interactions reinforced by social dynamics. We argue that such engagements hold potential not only for strengthening bonds with other-than-human companions but also for fostering environmental consciousness. Future longitudinal studies could examine how these designed encounters with plant care—especially when shared with others—might support broader practices of environmental stewardship. Inspired by perspectives in Human-Computer-Biosphere Interaction [48], we see value in investigating how domestic ecologies of care might be meaningfully linked to wider, even remote, ecological concerns, cultivating an ethos of mutual care that spans beyond the immediate home.

6 Conclusion

Using a moss terrarium as a minimal intervention and a co- ethnographer, our study found that in everyday domestic life, social and family cultures of plant care play a key role in fostering individual concern and accountability for houseplants and how they are framed. Put simply, we commonly learn to practically, emotionally, and morally care for houseplants from our family and friends. This challenges short-term, individual-focused HPI interventions, suggesting that social and domestic environments should be considered when designing HPI interventions and research. In this approach, technology's role can be to enhance communal care, facilitate shared experiences and responsibilities, and encourage knowledge exchange by acting as a central point of interaction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Intelligent Games and Game Intelligence (IGGI).

References

- Sara Adhitya, Beck Davis, Raune Frankjaer, Patricia Flanagan, and Zoe Mahony. 2016. The BIOdress: a body-worn interface for environmental embodiment. In Proceedings of the TEI’16: Tenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction. 627–634.

- Ahu Aydogan and Ryan Cerone. 2021. Review of the effects of plants on indoor environments. Indoor and Built Environment 30, 4 (2021), 442–460.

- Purav Bhardwaj and Cletus V Joseph. 2020. Plantimate: Personality augmentation for fostering empathy towards plants. In Companion Publication of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. 563–567.

- James Blake. 1999. Overcoming the ‘value-action gap'in environmental policy: Tensions between national policy and local experience. Local environment 4, 3 (1999), 257–278.

- Eli Blevis. 2007. Sustainable interaction design: invention & disposal, renewal & reuse. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. 503–512.

- Ian Bogost. 2012. Alien phenomenology, or, what it's like to be a thing. U of Minnesota Press.

- Fadi Botros, Charles Perin, Bon Adriel Aseniero, and Sheelagh Carpendale. 2016. Go and grow: Mapping personal data to a living plant. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces. 112–119.

- Christina Bremer, Bran Knowles, and Adrian Friday. 2022. Have we taken on too much?: A critical review of the sustainable HCI landscape. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–11.

- Tina Bringslimark, Terry Hartig, and Grete G Patil. 2009. The psychological benefits of indoor plants: A critical review of the experimental literature. Journal of environmental psychology 29, 4 (2009), 422–433.

- Giulia Carabelli. 2021. Plants, Vegetables, Lawn: Radical Solidarities in Pandemic Times. Lateral 10, 2 (2021). https://www.jstor.org/stable/48671655

- Michelle Chang, Chenyi Shen, Aditi Maheshwari, Andreea Danielescu, and Lining Yao. 2022. Patterns and opportunities for the design of human-plant interaction. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference. 925–948.

- Dominique Chen, Young Ah Seong, Hiraku Ogura, Yuto Mitani, Naoto Sekiya, and Kiichi Moriya. 2021. Nukabot: Design of care for human-microbe relationships. In Extended abstracts of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing Systems. 1–7.

- Silvia Collado, Henk Staats, and Patricia Sancho. 2019. Normative influences on adolescents’ self-reported pro-environmental behaviors: The role of parents and friends. Environment and Behavior 51, 3 (2019), 288–314.

- Ashley Colley, Özge Raudanjoki, Kirsi Mikkonen, and Jonna Häkkilä. 2019. Plant shadow morphing as a peripheral display. In Proceedings of the 18th international conference on mobile and ubiquitous multimedia. 1–5.

- Aykut Coskun, Nazli Cila, Iohanna Nicenboim, Christopher Frauenberger, Ron Wakkary, Marc Hassenzahl, Clara Mancini, Elisa Giaccardi, and Laura Forlano. 2022. More-than-human Concepts, Methodologies, and Practices in HCI. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts. 1–5.

- Judith IM De Groot and Linda Steg. 2007. Value orientations and environmental beliefs in five countries: Validity of an instrument to measure egoistic, altruistic and biospheric value orientations. Journal of cross-cultural psychology 38, 3 (2007), 318–332.

- Donald Degraen, Felix Kosmalla, and Antonio Krüger. 2019. Overgrown: Supporting plant growth with an endoskeleton for ambient notifications. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–6.

- Donald Degraen, Marc Schubhan, Kamila Mushkina, Akhmajon Makhsadov, Felix Kosmalla, André Zenner, and Antonio Krüger. 2020. AmbiPlant-Ambient Feedback for Digital Media through Actuated Plants. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–9.

- Carl DiSalvo, Phoebe Sengers, and Hrönn Brynjarsdóttir. 2010. Mapping the landscape of sustainable HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 1975–1984.

- Benjamin C Effinger. 2022. Ecological Homemaking: Houseplants in University Students’ Homemaking Practices During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ph. D. Dissertation. UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO.

- Till Fastnacht, Abraham Ornelas Aispuro, Johannes Marschall, Patrick Tobias Fischer, Sabine Zierold, and Eva Hornecker. 2016. Sonnengarten: Urban light installation with human-plant interaction. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing: Adjunct. 53–56.

- Jan Fell, Pei-Yi Kuo, Travis Greene, and Jyun-Cheng Wang. 2022. A biocentric perspective on HCI design research involving plants. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 29, 5 (2022), 1–37.

- Owen Noel Newton Fernando, Adrian David Cheok, Tim Merritt, Roshan Lalintha Peiris, Charith Lasantha Fernando, Nimesha Ranasinghe, Inosha Wickrama, Kasun Karunanayaka, Tong Wei Chua, and Christopher Aldo Tandar. 2009. Babbage cabbage: Empathetic biological media. In Proceedings of the Virtual Reality International Conference: Laval Virtual (VRIC’09). 20–23.

- Christopher Frauenberger. 2019. Entanglement HCI the next wave?ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 27, 1 (2019), 1–27.

- Anne Galloway. 2016. More-Than-Human Lab: Creative Ethnography after Human Exceptionalism. In The Routledge Companion to Digital Ethnography. Routledge. Num Pages: 8.

- Gionata Gatto and John R. McCardle. 2019. Multispecies Design and Ethnographic Practice: Following Other-Than-Humans as a Mode of Exploring Environmental Issues. Sustainability 11, 18 (Jan. 2019), 5032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11185032 Number: 18 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.

- Bill Gaver, Tony Dunne, and Elena Pacenti. 1999. Design: cultural probes. interactions 6, 1 (1999), 21–29.

- Alfred Gell. 1998. Art and agency: an anthropological theory. Clarendon Press.

- Elisa Giaccardi, Nazli Cila, Chris Speed, and Melissa Caldwell. 2016. Thing ethnography: Doing design research with non-humans. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM conference on designing interactive systems. 377–387.

- Elisa Giaccardi, Johan Redström, and Iohanna Nicenboim. 2024. The making (s) of more-than-human design: introduction to the special issue on more-than-human design and HCI. 16 pages.

- Elisa Giaccardi, Chris Speed, Nazli Cila, and Melissa L. Caldwell. 2016. Things as Co-Ethnographers: Implications of a Thing Perspective for Design and Anthropology. In Design Anthropological Futures. Routledge. Num Pages: 14.

- Elisa Giaccardi, Chris Speed, Nazli Cila, and Melissa L Caldwell. 2020. Things as co-ethnographers: Implications of a thing perspective for design and anthropology. In Design anthropological futures. Routledge, 235–248.