Preserving Writer Values in AI Writing Assistance Tools

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3690712.3690727

In2Writing '24: The Third Workshop on Intelligent and Interactive Writing Assistants, Honolulu, HI, USA, May 2024

Many creative writers see writing as a deeply personal, human endeavor rather than a means to an end. As LLMs stand to transform how we conduct and perceive writing, how can AI writing tools assist creative writers without conflicting with the values they hold dear? We interview 8 creative writers who extensively use AI writing tools to understand their core writing values and how these shape their use of AI. Our preliminary findings indicate writers prioritize personal values of authentic self-expression and love of process when deciding if and how to employ AI writing aids. We conclude by proposing design implications for AI assistants that uphold writers’ values.

ACM Reference Format:

Alicia Guo, Leijie Wang, Jeffrey Heer, and Amy Zhang. 2024. Preserving Writer Values in AI Writing Assistance Tools. In The Third Workshop on Intelligent and Interactive Writing Assistants (In2Writing '24), May 11, 2024, Honolulu, HI, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA 4 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3690712.3690727

1 Introduction

Recent large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated significant advances in the area of creative writing applications, ranging from poems [2] and video scripts [15] to screenplays [10]. Beyond traditional performance metrics like accuracy [11], coherency, and relevance [9], these AI-powered writing tools have further demonstrated their potential in the context of creative writing to proofread texts [1], describe scenes and characters, and inspire creative writers [5].

Despite the benefits of AI writing tools, their possible conflict with values core to writers may limit their appeal. Are writers transitioning from being the primary creators to mere curators in co-writing processes? If used carelessly, these tools may override creative writing's inherent values as a deeply personal, human endeavor. This research investigates writers’ core values, examining how those beliefs guide their application of AI writing aids. Interviews with 8 creative writers reveal a strong emphasis on ownership from a lens of authentic expression, as well as writer considerations on what makes the process enjoyable.

We find that writers use AI to unblock themselves, preferring aid where they struggle in the writing process, while limiting its role to keep the enjoyment of the process. As we move forward, it is crucial to engage in ongoing dialogue with the writing community to ensure that AI tools enrich the writing landscape, fostering creativity while preserving the cherished values of authenticity and personal engagement in the creative process.

2 Related Work

Support for writing through computational means has evolved significantly, beginning with the advent of initial spell-checkers [13] and advancing to contemporary software that guides story creation [3]. These tools serve various purposes, from simplifying the task of texting [14] and assisting in selecting words with precise connotations [4], to enhancing emotional writing [12], and facilitating writing in professional settings [7].

While prior research has engaged real-world writers to evaluate the capabilities of AI writing tools, it often conducted their evaluation in a controlled lab setting: writers are invited to communicate their needs with researchers and then try using the implemented prototypes for some predefined tasks. These evaluations have often prioritized system usability and user engagement. As a result, little research has examined how writers might use these AI-powered writing tools in their daily writing experience. However, the daily writing experience is a deeply personal and human endeavor to these creative writers. Without a close examination of their daily writing experience, it is unlikely to observe how these writing tools might compromise the intrinsic values of writing. Prior interview studies have explored writerly values on receiving support in the writing process [6]. Others have explored longer term insights from professional writers using an AI tool, examining how these tools integrate into and affect the daily creative processes [8].

3 Methods

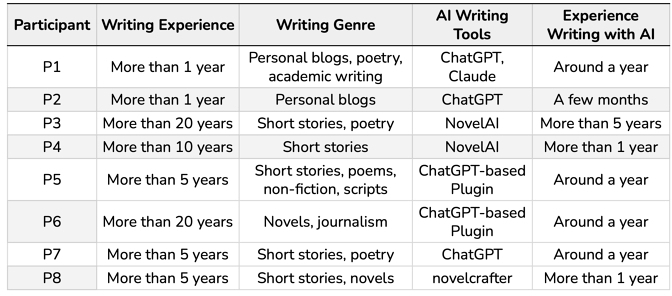

We conducted 8 semi-structured interviews with writers who regularly use AI (6 fiction writers, 2 blog writers) detailed in Appendix 1. Our interview questions are structured to understand writers’ interactions with AI tools across different stages of the writing process for all manners of tasks (grammar checks, writing prose, brainstorming ideas, and developing characters). Interviews lasted 90 minutes, with 30–40 minutes spent observing live-writing sessions where participants continued or began new pieces and discussed prior AI-assisted work (Appendix A.2). This was presented as time for participants to work on what they would have even had they not participated in the interviews. This enables us to capture the nuanced interactions in the translating and reviewing stages, as well as to gain insights into the role of AI in the planning phase of writing. We are especially interested in writers’ motivations around using, not using, or correcting AI output. For the majority of our interviews, participants stated that they would not have done things differently without observation, with one participant answering that they would have written more slowly if not observed. Each participant was paid $40 in the form of gift cards. This study was reviewed by our IRB and deemed exempt.

4 Preliminary Findings

We analyzed the interviews with the first author leading the open coding process. We find two values that writers cherish: 1) authentic expression, or the feeling that the writing is true to their vision and original expression, with the AI helping them achieve it; and 2) the love of the writing process, or specific aspects of writing that they would like to preserve, even while using AI. We also observe a tension between how some writers rationally view their use of AI and how they feel.

4.1 Writers value authentic expression and use AI to help achieve it

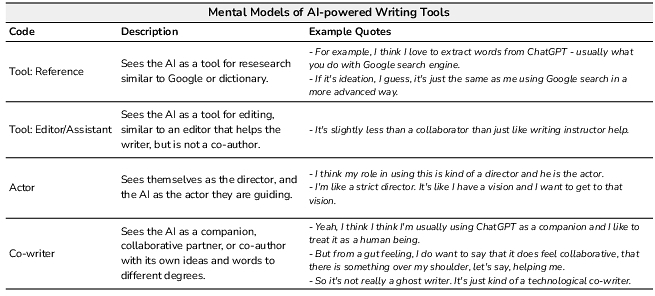

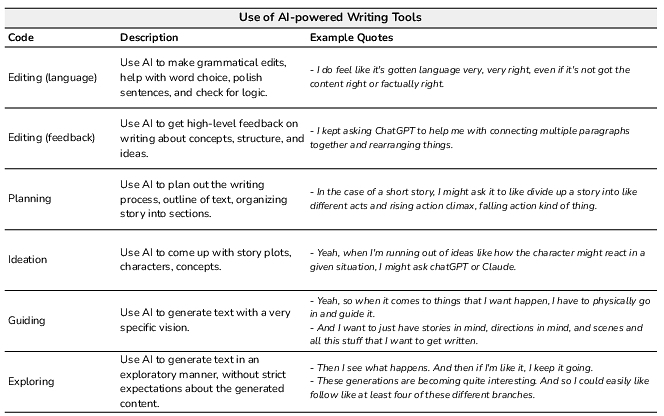

We detail the ways writers interact with AI in Appendix B.2. In order to preserve the value of authentic expression, many writers spend significant effort to iteratively prompt a model to achieve output that aligns with their vision, rejecting along the way content that does not feel authentic to them. For example this can come in the form of sentence level syntax, stylistic elements, or adherence to the author's vision for plot or characters. One might ask why spend this time trying to guide a model instead of simply doing the writing. For most of our interviewees, it was a tool for getting unstuck. A main reason many of our participants turned to AI was to speed up their writing process, with a large portion of the benefit coming from overcoming writers’ block. Oftentimes, the writers had their own ideas on how they would like their story to proceed and would use AI to help connect plot points, generate continuations, or suggest ideas, emphasizing that even unsatisfactory generations can still be useful to move the writing forward. Mental models of AI-powered writing tools (Appendix B.1) also affect perception of ownership (utilizing AI as a tool retains full ownership), yet there are still ambiguities—some see ownership concerning legal rights, others in terms of authorial pride.

4.2 Writers retain a love of the writing process

Many writers stated that if AI generated the majority of the content and ideas for a story, it would not be enjoyable to write and they would not use AI. On the other hand, P5 had a different stance of wanting the AI to generate the majority of the text, but in a way that represented their own writing and stayed consistent with their story. Other writers, while wanting AI involvement to different degrees, still valued consistency with their own voice and style. Each writer had different aspects of the writing process that they enjoyed, such as coming up with ideas for the story or characters, writing dialogue, and turned to the AI for aspects that they struggled with, such as first drafts or connecting plot points.

4.3 Writers are still negotiating their relationship with LLMs in their work

We noticed two types of tensions amongst writers in how they viewed the use of AI. In one, the way in which they would like to see the AI or could reason rationally (e.g. as a tool) did not match up exactly with how they felt (a hint of some intelligence or collaboration) and these tensions remain unresolved. In the other, especially with the two blog writers who used AI less extensively for text generation, this was the first time they tried to articulate their thoughts on the matter of devaluing AI text, and would go back and forth between a gut reaction to what they would then reason rationally. This tension is partly attributable to the unsettled public discourse surrounding generative AI.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Our preliminary findings highlight the importance of authentic expression in writers’ interactions with AI in the context of how each individual writer expresses these values, whether that is through the ideas or prose itself. We find that one of the main benefits to using AI in the writing process is getting unstuck, which can inform design decisions for future creative writing applications. These tools should aim to support aspects of the process that writers dislike while preserving the aspects that they enjoy. One direction of exploration could be to focus more on a notion of closeness to the vision of the writer as a metric. We see that writers are still working out their relationship to LLMs and how to negotiate their values. In addition, the current stigma surrounding using AI for writing complicates how writers would like to share their work. Another avenue of exploration is tracking the provenance of a written piece, so that authors can track where suggestions came from at different levels of sentences, paragraphs, beats, and overarching ideas. Not only does this enable them to reflect on their usage of these tools, it may provide a way to be transparent about how AI was used that also shows their own effort and creative vision in the process, especially with the insight that AI use that doesn't contribute directly to the text output can still be helpful to the writing process. In continuing our research, we wish to ask what makes a good AI writing assistant that puts writers’ values first? How do we think about where, when, and how much the AI should be involved compared to the writer?

References

- Alex Calderwood, Vivian Qiu, Katy Ilonka Gero, and Lydia B Chilton. 2020. How Novelists Use Generative Language Models: An Exploratory User Study.. In HAI-GEN+ user2agent@ IUI.

- Tuhin Chakrabarty, Vishakh Padmakumar, and He He. 2022. Help me write a poem: Instruction Tuning as a Vehicle for Collaborative Poetry Writing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.13669 (2022).

- John Joon Young Chung, Wooseok Kim, Kang Min Yoo, Hwaran Lee, Eytan Adar, and Minsuk Chang. 2022. TaleBrush: Sketching stories with generative pretrained language models. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–19.

- Katy Ilonka Gero and Lydia B Chilton. 2019. How a Stylistic, Machine-Generated Thesaurus Impacts a Writer's Process. In Proceedings of the 2019 on Creativity and Cognition. 597–603.

- Katy Ilonka Gero, Vivian Liu, and Lydia Chilton. 2022. Sparks: Inspiration for science writing using language models. In Designing interactive systems conference. 1002–1019.

- Katy Ilonka Gero, Tao Long, and Lydia B Chilton. 2023. Social dynamics of AI support in creative writing. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–15.

- Julie S Hui, Darren Gergle, and Elizabeth M Gerber. 2018. Introassist: A tool to support writing introductory help requests. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–13.

- Daphne Ippolito, Ann Yuan, Andy Coenen, and Sehmon Burnam. 2022. Creative Writing with an AI-Powered Writing Assistant: Perspectives from Professional Writers. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.05030

- Chin-Yew Lin. 2004. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text summarization branches out. 74–81.

- Piotr Mirowski, Kory W Mathewson, Jaylen Pittman, and Richard Evans. 2023. Co-Writing Screenplays and Theatre Scripts with Language Models: Evaluation by Industry Professionals. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–34.

- Kishore Papineni, Salim Roukos, Todd Ward, and Wei-Jing Zhu. 2002. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 311–318.

- Zhenhui Peng, Qingyu Guo, Ka Wing Tsang, and Xiaojuan Ma. 2020. Exploring the effects of technological writing assistance for support providers in online mental health community. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1–15.

- James L Peterson. 1980. Computer programs for detecting and correcting spelling errors. Commun. ACM 23, 12 (1980), 676–687.

- Philip Quinn and Shumin Zhai. 2016. A cost-benefit study of text entry suggestion interaction. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 83–88.

- Sitong Wang, Samia Menon, Tao Long, Keren Henderson, Dingzeyu Li, Kevin Crowston, Mark Hansen, Jeffrey V Nickerson, and Lydia B Chilton. 2023. ReelFramer: Co-creating News Reels on Social Media with Generative AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.09653 (2023).

A Study summary

A.1 Participants

A.2 Study procedure

Section I: On-boarding ( 15 minutes) We started the interview by briefing participants with an overview of the interview session. We then asked participants about set of background and onboarding questions regarding participants’ writing practices and AI assistance in general. Examples of questions include “Which aspect of your writing experience do you enjoy the most”, and “What AI-powered writing tools you have used”.

Section II: Live Writing ( 30 minutes) During the interview, participants were invited to live-write a creative piece using AI writing tools and their unique workflows. While some AI writing tools can document editing or interaction history, a live writing session provided us with the opportunity to observe the nuanced and dynamic interactions between the user and the AI tools, including some that may be subtle and not immediately recognized by the writers during the writing process. During these live writing sessions, we prioritized avoiding any interruptions to maintain the natural flow of the writing process. Instead, we focused on taking detailed notes and formulated follow-up questions to be discussed in the subsequent session.

Section III: Walkthrough of Previous Writing ( 20 minutes) Participants were also invited to share a piece of writing they had previously finished with the assistance of AI writing tools. We asked questions about what they remembered of the steps of the process as well as reflections of their views on creativity, attribution and ownership, and important moments.

Section IV: Follow-up Questions (25 minutes) In this section, our follow-up questions focused on the role of AI tools in the three cognitive processes of writing. Our aim was not only to understand how these tools are being used but also to explore the reasons behind the non-use of certain AI functionalities, which might reveal underlying value conflicts. Specifically, we delved into their experiences of co-creating a creative text with AI assistance. While the live writing session provided insights into the detailed interactions during the actual writing of paragraphs, these conversations allowed us to explore the role of AI in the planning stage of writing, such as the planning and development of character personas and story plots. We also asked participants to share their views on the value of AI written text and any ethical concerns.

Some participants did not do Section III of sharing a previous piece of writing due to time constraints or comfort. With the concern that some participants may not feel comfortable writing while being observed, we offered the options of letting participants be able to 1) pre-record a writing session conducted individually and then sharing for the interview followup or 2) conducting the writing session without recording and taking notes on the process to be shared and explained during the interview followup. Questions were skipped or added by the researcher according to the relevance to the participant's genre and background.

B Codes from findings

B.1 Mental Models of AI-powered Writing Tools

B.2 Resultant Collaboration with AI-powered Writing Tools

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 License.

In2Writing '24, May 11, 2024, Honolulu, HI, USA

© 2024 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-1031-5/24/05.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3690712.3690727