HygroShape: Programming Flat-pack, Self-shaping Wood Furniture

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3745778.3766658

SCF '25: ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication, Cambridge, USA, November 2025

Wood is inherently hygromorphic, shrinking and swelling with changes in moisture. The combination of high actuation force, material stiffness, and accessibility, make wood an ideal smart material for large scale applications (cm – m scale) [Rüggeberg and Burgert, 2015], [Zambrano-Jaramillo et al., 2024]. Inspired by the scales of conifer cones' natural change in shaping through desorption we design and fabricate a system for self-shaping, flat-pack furniture from bilayer wood sheets that transform to curved configurations simply through air drying. The system can be manufactured using standard processes and actuates fully autonomously in normal interior conditions in Western Europe (30-60% relative humidity at 20-26°C according to [CEN, 2019]) into the designed shape. Within a defined design space, we show that by using a computational design-to-fabrication process we can: tune the direction and magnitude of curvature, combine multiple parts to form larger functional, deployable mechanisms, and create usable furniture. Compared to other self-shaping and deployable material systems, our system shapes completely autonomously and passively in typical interior environments, and is made with sustainable and attainable wood materials and simple processing. Beyond proposing a fabrication strategy for flat-pack furniture, the work raises new questions about the role of dynamic materials in interior environments and suggests opportunities for integrating material-driven shape change into design processes.

ACM Reference Format:

Laura Kiesewetter, Dylan Wood and Achim Menges. 2025. HygroShape: Programming Flat-pack, Self-shaping Wood Furniture. In ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication (SCF '25), November 20-21, 2025, Cambridge, MA, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 24 Pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3745778.3766658

1 Introduction

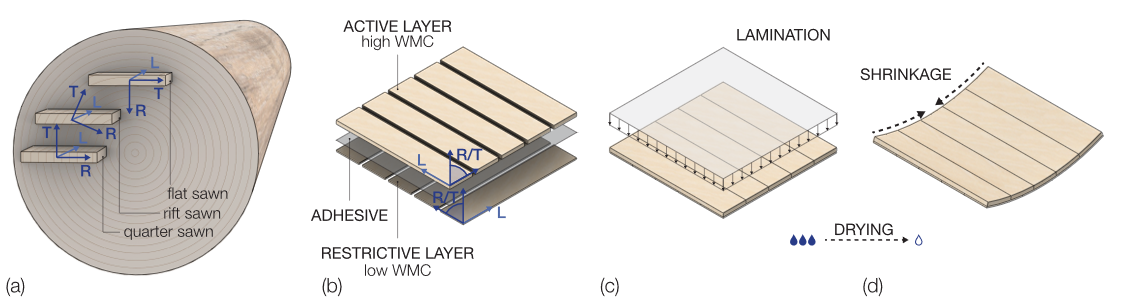

1.1 Self-shaping wood

In the furniture industry, wood has traditionally held a dominant position due to its widespread local availability, relative ease of processing, and robust structural performance. Woodworkers and carpenters commonly exploit its well-understood anisotropic properties, particularly utilising the stronger primary fibre direction for principal load-bearing elements such as stool or table legs. However, the hygromorphic properties of wood are conventionally regarded as a significant drawback. The volumetric deformation of wood is often observed in the subtle dimensional changes of doors that fail to close properly with seasonal shifts, frequently leading to undesirable deformations such as cupping, twisting, bowing, or even cracking [Hoadley, 2017]. Crucially, the shape changes in the radial (R) and tangential (T) directions of the annual rings are considerably more pronounced compared to the largely insignificant changes in the longitudinal (L) direction, which runs parallel to the tree stem. Furthermore, tangential shape changes are typically slightly stronger than radial ones. Depending on how a board is sawn—be it plain-sawn, quarter-sawn, or rift-sawn—the dominant dimensional change along its width can be predominantly radial or tangential (see Figure 1 a). Efforts to mitigate these strong and directionally dependent shape changes have led to the fabrication of processed cross-laminated wood products, such as laminated veneer lumber, plywood, cross-laminated timber (CLT), and particleboards, with the explicit aim of achieving material homogeneity and reducing these active hygromorphic properties [Young, 2007].

In stark contrast to this conventional approach, nature provides compelling examples where the very same cellular phenomena that cause these unwanted deformations are harnessed to advantage. A notable instance is found in conifer cone scales, where elongated fibre cells are arranged in a double-layered configuration at the meso-scale (arrangement of tissue layers). This structural organisation translates anisotropic shape change, occurring at the micro-scale (cellular and subcellular level), into a precisely pre-programmed shape change at the macro-scale (cone scales). This mechanism enables conifer cone scales to open completely passively in response to external stimuli, specifically changes in ambient relative humidity (RH) throughout the seasons, reliably and without any energy input, including metabolic energy from the tree itself [Dawson et al., 1997].

Instead of attempting to mitigate the inherent hygromorphic properties of wood, this natural principle can be harnessed for the passive generation of curvature [Reyssat and Mahadevan, 2009]. Previous research has demonstrated that, analogous to the lamellar structure of conifer cone scales, a double-layered, cross-laminated wood plate, referred to as a 'bilayer', can passively deform into a programmed curvature (see Figure 1 b-d). In the manufacturing process, an 'active' layer is prepared with an elevated wood moisture content (WMC). The 'restrictive' layer is typically significantly thinner to facilitate a higher degree of curvature. When these two layers are bonded together, the differential dimensional shrinkage in the R and T directions within the active layer, occurring during the drying process, can be exploited to passively generate curvature.

Furthermore, preceding research has established that this phenomenon can be predicted with considerable reliability using an adjusted version of Timoshenko's bilayer theory [Rüggeberg and Burgert, 2015], [Timoshenko, 1925]. To fully facilitate the design and fabrication potentials of materially programmed self-shaping wood elements, robust computational strategies are necessary.

1.2 Practices in furniture industry

In current furniture manufacturing practices, the creation of organic, curved shapes often incurs significant costs, primarily due to the necessity for large transport volumes and intensive machining processes. This approach typically demands expensive presses and necessitates large production batches, as the processing often involves shaping in three dimensions. An alternative strategy widely adopted in the industry is the design of furniture for flat-pack delivery, which shifts the assembly task to the end-user. While this reduces transport volume and manufacturing complexity, it frequently leads to lower quality of the assembled product and a shorter product lifespan due to inexpert assembly [Safi, 2022]. Furthermore, this design approach often compromises the aesthetic and functional integrity of the final product, sacrificing design intent for logistical efficiency.

1.3 Hypotheses and contributions

We investigate the use of the intrinsic hygromorphic property of wood to enable the passive, material-driven transformation of flat-packed bilayer sheets into three-dimensional curved furniture. By leveraging hygroscopic actuation, we seek to advance design and fabrication strategies for autonomous self-shaping systems suitable for interior furniture. These systems are specifically designed to be fabricated flat, transported in a compact flat-pack configuration, and subsequently self-shape autonomously under typical interior conditions (30-60% RH at 20-26°C according to [CEN, 2019] in Europe). This endeavour necessitates the development of a comprehensive material programming workflow capable of supporting the design, fast and reliable prediction, and precise fabrication of such self-shaping wood furniture. Furthermore, a key aspect of our work explores how the inherent material heterogeneity can inform and drive the iterative design process itself.

2 Related work

2.1 Self-shaping wood in architecture

Within the architectural context, we distinguish three primary avenues for the application of self-shaping wood.

The first avenue explores the use of self-shaping for prefabricating load-bearing, surface-active curved CLT components. Projects such as the Urbach Tower [Wood et al., 2020] and Wangen Tower [Alvarez et al., 2025] demonstrate how self-shaping can be integrated into an industrial workflow: large-format bilayers are fabricated flat and then shaped under controlled conditions in an industrial kiln during a standard drying cycle and are consequently glued together into CLT. As shaping occurs in the factory, these elements must be transported in their final, curved state, resulting in volumetric shipping. In this context, self-shaping is primarily used to generate architectural form, but the reliance on artificial environmental control for drying and the handling of pre-curved components still pose fabrication and logistical challenges.

The second avenue, moving in an opposite direction, focuses on the use of self-shaping devices for responsive and adaptive building applications, such as shading. These meteorosensitive building skins are designed to open and close in response to fluctuations in ambient RH. Responsive shading devices made from wood have been tested in prototypes [Bridgens et al., 2017]. More recently, the concept has evolved into wood-based 4D-printed elements and has already been integrated into an architectural demonstrator [Cheng et al., 2024]. These devices capitalise on simplified flat fabrication and their inherent shape-changing, responsive capacity, without aspiring to fulfil any load-bearing function.

The third avenue, and arguably the most relevant for our research, encompasses the use of self-shaping both for the generation of form in load-bearing, surface-active building components and for supporting on-site assembly. While previous research exploring more freeform geometries has largely remained at a conceptual level [Wood et al., 2018], the Hygroshell research pavilion stands as the first 1:1 scale demonstrator, albeit highly experimental [Wood et al., 2023], [Takahashi et al., 2024]. In the Hygroshell research pavilion, bilayers are manufactured flat and subsequently processed into building components, complete with the necessary detailing for connections and building skin, all while remaining in their flat state and maintaining a higher WMC. These flat components are then transported to the site in a compact package. Only upon exposure to drier ambient conditions on site do they self-shape, thereby minimising on-site assembly work and scaffolding requirements. Consequently, the self-shaping capacity is employed not only to generate form but also to facilitate efficient flat-pack transportation and enable partial self-assembly. While a building, even an experimental research pavilion like the Hygroshell, represents a complex system with demands concerning structural integrity and weather protection, achieving completely autonomous assembly remains a significant challenge. Given the comparatively reduced complexity required for interior furniture, this application scenario presents a highly promising use case for the material system. An interior actuation also typically experiences fewer fluctuations in ambient conditions. This research, to our knowledge, marks the first exploration of self-shaping wood for furniture applications.

2.2 Self-assembling and deployable furniture

Various approaches to self-assembling furniture-scale objects have been explored, particularly using textile actuators [Kamijo and Tachi, 2024]. These systems often rely on tailored fibre placement on pre-stressed membranes, but face a core dilemma: structures are either too stiff to bend or too weak to carry load [Aldinger et al., 2018]. Significant pre-stress would be required to achieve structural function, raising concerns around stability and user safety. Moreover, such systems often depend on materials and fabrication techniques not commonly used in furniture production. A hybrid approach by the MIT Self-Assembly Lab uses wood as the structural element and textiles primarily to guide assembly, though it remains limited in scale and geometric flexibility [Tibbits et al., 2015]. Other textile-based solutions involving shape memory alloys or smart materials offer little structural performance and are mainly suited to specialized, small-scale applications like prosthetics or soft robotics [Kongahage and Foroughi, 2019].

Beyond textiles, 4D printing represents a rapidly developing research area, though it predominantly operates at a small scale [Cheng et al., 2021a]. While examples at furniture scale exist, the use of 3D-printed plastic is not generally a favourable material in the furniture industry, and fabrication speed might become an issue when scaling up to larger quantities, with size often limited by the printer's build volume [Wang et al., 2018]. Relevant work on robotic 3D printing of self-shaping bilayers has shown potential but has not been extended to interior furniture applications [Özdemir et al., 2022], [Cheng et al., 2021b]. Similarly, flat-pack furniture and design objects made from cellulose sponge, actuated by moisture, offer an innovative and appealing approach to flat-pack interior objects. However, this method requires water as an external actuator for the shaping process, and the robustness and structural capacity of the final product, remain inherently limited [ECAL, 2024]. Our work specifically investigates the application of self-shaping wood in the previously unexplored area of interior furniture. We position ourselves within the field of self-assembling and deployable furniture, aiming to contribute a load-bearing, safe-to-use approach that actuates fully autonomously purely by exposure to ambient indoor conditions.

2.3 Material-informed computational design-to-manufacturing workflows

Designing with natural, shape-changing materials requires workflows that integrate material behavior into the digital design-to-manufacturing process. In 4D printing, such workflows link material-specific structuring with simulations of the resulting 3D shape, allowing precise control over anisotropy despite uniform material composition [Tahouni et al., 2020]. Similar strategies are used in shape-changing edible films made from gelatin, cellulose, and starch, where behavior is designed and predictable, without the need to account for natural variability [Wang et al., 2017]. At the architectural scale, some workflows address the anisotropy of wood, as seen in the RawLam project, which uses high-resolution material data for board allocation within glulam beams [Svilans and Ramsgaard Thomsen, 2024]. However, these approaches do not engage with wood's hygromorphic properties or its potential for passive, moisture-driven shape change.

3 Integrative computational workflow

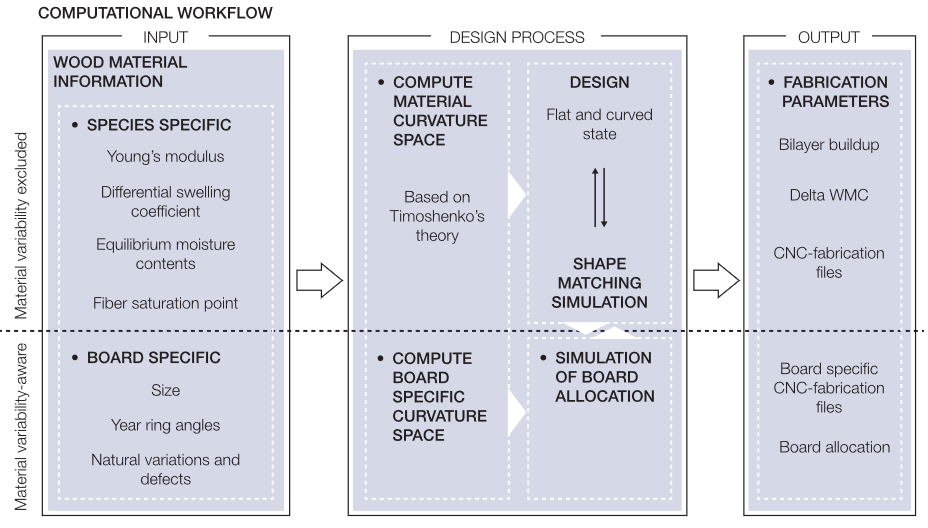

This chapter outlines the methodology for designing and fabricating self-shaping furniture prototypes, including material characterisation, curvature prediction, and the iterative design process (Figure 2). It also covers the digital fabrication workflow, handling of material variability , and methods for documenting and analysing the shape change.

3.1 Material information

The foundation of the computational design process was the comprehensive material information. For each wood species, several physical and mechanical properties were of importance, including the Young's modulus, the swelling coefficient, the equilibrium moisture content at the targeted interior conditions, and the fibre saturation point. While the Young's modulus E describes the stiffness of the material, meaning its resistance to elastic deformation, the differential swelling coefficient quantifies the difference in dimensional change in the distinct fibre directions L, R and T in response to a change in moisture content. The fibre saturation point is the moisture content at which the cell walls are fully saturated with bound water, but no free water exists in the cell lumens. Above the fibre saturation point, additional moisture is free water and does not cause further dimensional change of the wood. The equilibrium moisture content is the moisture content that wood eventually reaches when exposed to a specific RH and temperature in its surrounding environment for a sufficient period, where it neither gains nor loses moisture [Rijsdijk and Laming, 1994].

In the context of this research, two specific wood species were procured: Sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) and wild cherry (Prunus avium). The physical and mechanical properties utilized for the computation of the curvature space for these species are detailed in Table 1.

| Wood species | Young's modulus [MPa] | Differential swelling coefficient [%-1] | Fibre saturation point [%] | Equilibrium moisture content in adsorption at ambient conditions (30-60% RH) [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) |

L: 14370 R: 1750 T: 1070 |

L: 0.0001 R: 0.0011 T: 0.0024 |

> 30 |

7.8-12.6 |

| Wild cherry (Prunus avium) |

L: 10620 R: 910 T: 2090 |

L: 0.00023 R: 0.0014 T: 0.0033 |

28 | 7.2-11.1 |

3.2 Curvature space

The basis for defining the curvature and material design space in our study was the Timoshenko formula, originally developed to describe deformation in bimetallic strips [Timoshenko, 1925]. Preceding research on self-shaping wood has adapted and rigorously tested this formula for its application in predicting the curvature $\frac{1}{\rho }$ of self-shaping wood bilayers (Equation 1) [Rüggeberg and Burgert, 2015]. The relevant physical properties considered in this formula are the Young's Modulus of the two layers, denoted as E₁ and E₂, and their respective differential swelling coefficients, α₁ and α₂. The parameters defining the bilayer configuration are the layer thicknesses, ℎ₁ and ℎ₂, and the WMC at the point of fabrication (c₀) and in the final curved state (c).

(1)

3.3 Computational and material design process

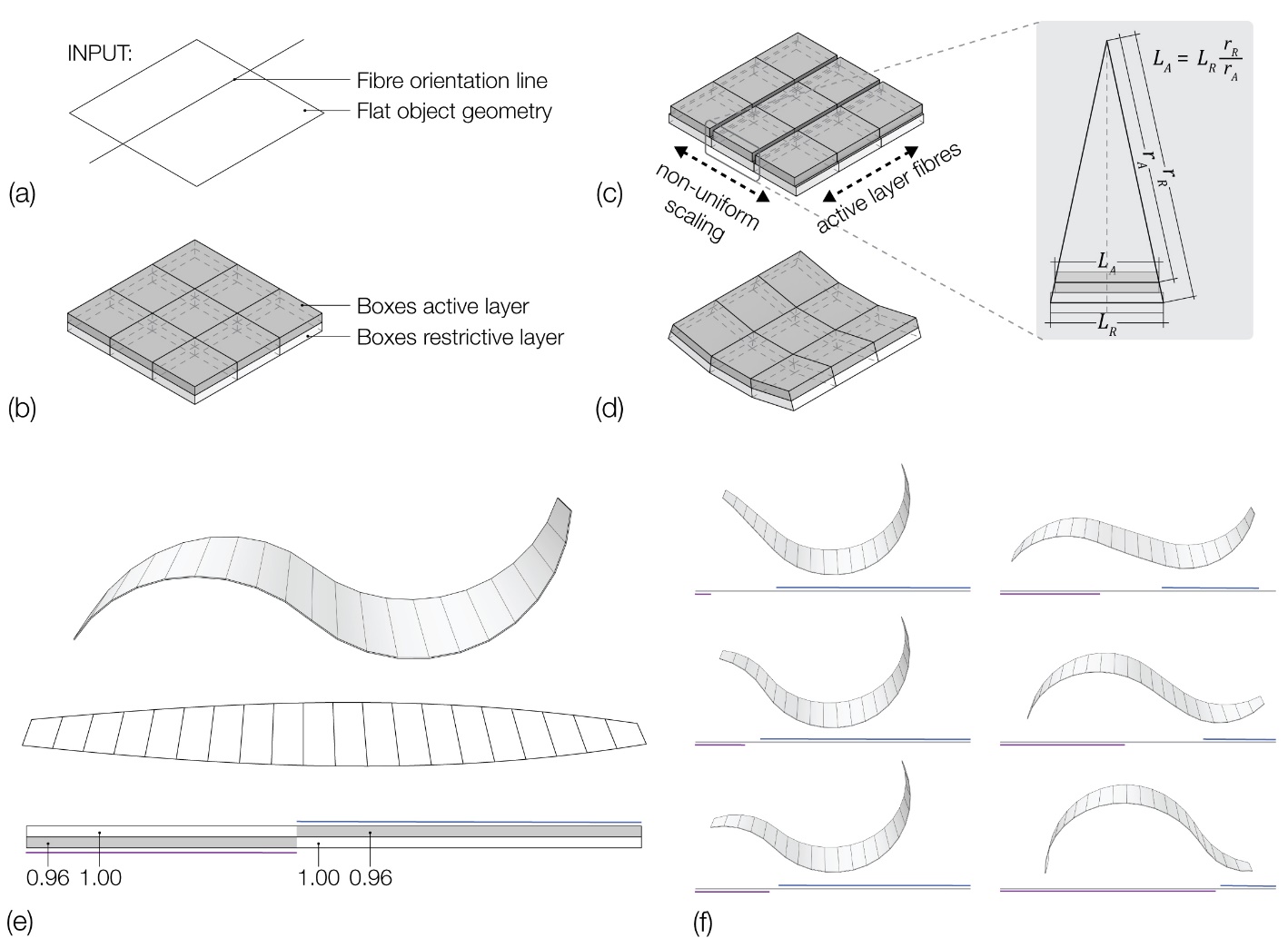

Using the adapted Timoshenko equation, literature values for E₁ and E₂ as well as α₁ and α₂ and measured values for each board for the start and end WMC and ℎ₁ and ℎ₂ we defined curvature values for a given stock of input boards. In case studies 1 and 2, boards were procured with tight specifications regarding grain angle and dimensions, resulting in clearly grouped curvature ranges. In contrast, case study 3 used boards derived from cutting a single short log, producing a limited and specific set of curvatures as the basis of the design. While the adapted Timoshenko equation is an efficient method for generating the board curvatures in relation to the available stock, it is difficult to design, visualize, and adjust geometry and larger mechanisms from curvature values. To address this we developed an interactive computational design workflow for an inverse design process inside Rhinoceros 3D (Version 7, McNeel, USA) and its visual programming environment Grasshopper (Build 1.0.0007) to rapidly design with and adjust self-shaping mechanisms. The workflow incorporates an adapted version of a constraint-based geometric solver, Shape-Up, implemented in C# as a custom goal component in the Kangaroo2 Plugin (Version 2.5.3, Daniel Piker)[Piker, 2013] , [Bouaziz et al., 2012]. Using the flexibility of the shape constraints based solver from Shape-Up inside of Rhino and Kangaroo our approach allows for quick, intuitive, and interactive exploration of 3D self-shaped geometries and their relationship to the arrangement and variation of properties in the physical wood boards (Figure 3 e,f). Compared to strict material modeling and Finite Element methods, our workflow focuses on larger board assemblies, is adept at handling large deformations, and offers near-live visual feedback.

In this method, flat geometries as surfaces and lines, indicating the fibre orientation of the active layer and thus controlling the direction of curvature, serve as input (Figure 3 a). In case board specific dimensions and curvatures are used, the input geometry must consist of separate surfaces or meshes for each board. The geometry is then transformed into a quad mesh with targeted, uniform edge lengths, and separate geometries (e.g. boards) are joined together. The mesh vertices serve as the basis for constructing twisted boxes using Grasshopper's native Twisted Box component, representing both the active and restrictive layers (Figure 3 b). A central element of the workflow is the non-uniform scaling of each twisted box. The base plane for this scaling operation is an XY plane placed at the centroid of each box and oriented according to the closest fibre orientation line. The scale factor LA/LR—where LA is the width of the active layer box and LR the corresponding width of the restrictive layer—is derived from curvature predictions computed with the Timoshenko formula and back-calculated using trigonometry (Figure 3 c). The relative position of the fibre orientation line determines the direction of curvature: if the line lies above the flat geometry, the boxes of the upper layer are defined as the active layer and thus receive the non-uniform scaling, while the boxes of the lower layer are defined as the restrictive layer and remain unscaled (factor = 1), and vice versa. The vertices of the boxes after the non-uniform scaling operation serve as the goal objects for the shape matching. After solving, the curved geometry is reconstructed from the output mesh (Figure 3 d).

Our case studies involved relatively small sets of curvature configurations and board counts, allowing for a clear and specific mapping between the curvature design space and the design geometry—even enabling manual assignment and sequencing of boards.

The flexibility and speed of this design method also make it suitable for integration with larger material databases and finer tuning of geometric parameters. In addition to the specification of boards in linear arrangements, multiple plates can be mechanically linked to form larger mechanisms. The workflow parametrically outputs a board list, quantity takeoff, and computer numerical control (CNC) milling details for both layers of the bilayer sheets.

3.4 Fabrication parameters and digital fabrication

The fabrication process commenced with the equalisation of boards designated for the active layer. These boards were conditioned in a high RH environment (approximately 95%) over a period of two to six months to achieve a homogeneous WMC throughout their entire cross-section. Following this, and based on the determined bilayer configuration, boards were planed to a thickness 2 mm greater than the desired final thickness for both the active and restrictive layers. This allowed for subsequent planing to the exact total thickness after the initial bilayer sheets had been produced, ensuring dimensional accuracy.

In the CNC-fabrication files, a slight offset was applied to the flat design outlines. This strategic offset facilitated a final contour CNC-cutting step, resulting in clean and precise edges. Both the active and restrictive layers were discretised into strips, ensuring that the strip width did not exceed the dimensions of the available stock boards. For each board in the active and restrictive layers of the flat design, a milling outline with rounded dovetail joints was generated. These joints facilitated easier handling during fabrication, as both layers could be preassembled into sheets. In the tested samples, the connections did not interfere with the self-shaping behavior of the bilayers. The detailed outlines were then nested onto the digital representation of the physical boards, optimising material utilisation, and subsequently CNC-cut.

Throughout the process, exposure of the active layer to ambient conditions was minimised; boards or segments were covered or stored in the high RH environment whenever possible to prevent premature drying. Once cut, the edges were sanded, and the individual segments were assembled into larger restrictive and active layer sheets. These sheets were then bonded and pressed together in a vacuum press, utilising a 1K PUR glue (Henkel LOCTITE HB S309). Following the pressing stage, a final routing pass was performed around the perimeter of the bilayer to account for any minor inaccuracies in layer placement and to remove excess adhesive. To achieve a clean and smooth surface finish, both faces of the bilayer were either surface routed or planed, followed by sanding. The final processing steps involved the integration of connection or locking details and, where applicable, the assembly of multiple bilayers to form the complete furniture piece.

3.5 Designing with material variability

The fabrication strategy outlined above largely adhered to a conventional timber processing paradigm, which typically presumed uniform performance across wood boards and relied on stringent selection criteria for high-quality timber. This included selecting material free from knots or branches and within a narrow range of allowable annual ring angles (e.g., 0° for rift-sawn or radial cut). Furthermore, the approach often assumed the use of standard board sizes, in this case active boards of 2000x150x20 mm and restrictive boards of 2000x150x10 mm. While this simplified the design and fabrication workflow, it imposed economic and ecological constraints on the proposed method, running counter to the inherently variable nature of wood as a natural material.

To embrace this natural variability, additional aspects were considered in the design process. Beyond the species-specific material properties, board-specific characteristics, including individual dimensions, annual ring angles, and natural variations or defects, were meticulously recorded and integrated as input (Figure 2). These parameters were added to a material library with unique identifiers for each board. With this comprehensive information, a curvature space could be computed for each individual board using Timoshenko's theory at a higher resolution to capture nuanced behaviour. For design guidance, a radius gradient was considered within this board-specific curvature space. This approach necessitated an iterative process with the shape matching simulation and board allocation, allowing for an estimation of how closely the simulation aligned with the target geometry and whether adjustments to the board allocation were required. Consequently, the CNC-files had to be generated to precisely account for each board's specific location and unique identifier. The outcomes of these board allocation iterations during the design process were then directly used to generate detailed board placement instructions for fabrication.

3.6 Self-shaping and geometric data acquisition

For actuation, the prototypes were placed in regular indoor conditions (around 23°C and 30% RH) under controlled lighting. To document the self-shaping process, a time-lapse recording was captured using two cameras (SONY ILCE-6100 and NIKON D7100), positioned to capture the prototype from different angles. One camera provided a frontal view, which was subsequently used for curvature evaluation during shaping.

To quantitatively assess the self-shaping performance, the following method for curvature analysis was employed. Fiji (version 2.16.0) was used for point extraction, where points were manually placed along the edge of each prototype [Schindelin et al., 2012]. Consistent placement of these points was ensured by orienting on visual markers, such as the edges of the active layer boards. Points were consistently placed on the concave side of the radius (corresponding to the outside edge of the active layer). Following point extraction, geometric processing and visualisation were performed with Matplotlib and in Rhino 8 with Grasshopper.

4 Case Studies

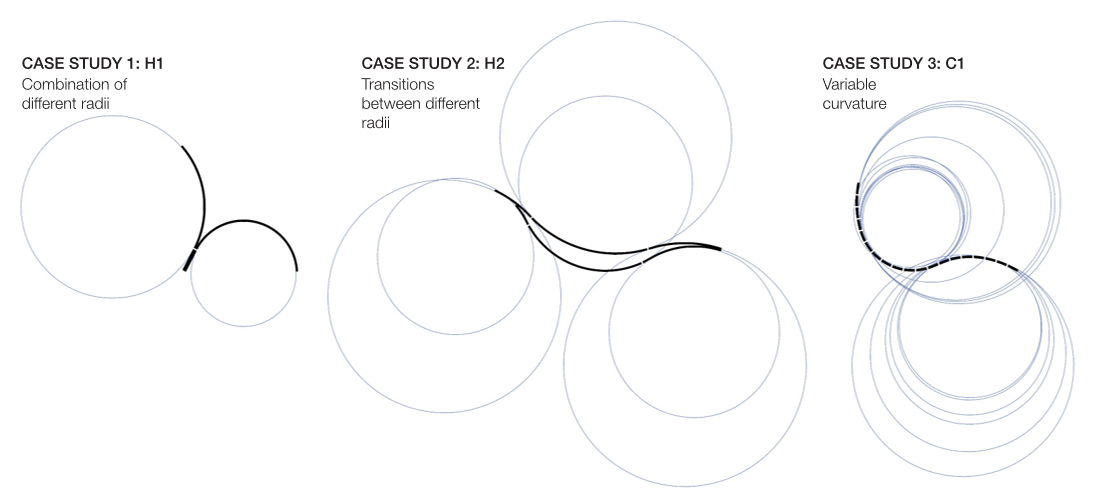

This chapter presents three case studies (Figure 4) that exemplify the application of our computational workflow for designing and fabricating self-shaping furniture. Each prototype was developed with specific geometrical and functional objectives. The first case study, H1, explored the simultaneous shaping of combined radii, demonstrating a dramatic transformation from a compact flat-pack configuration to the expansive geometry of an upright lounge chair. H2 geometrically showcased the transition between opposite curvatures, forming a more complex S-shape, and functionally integrated a simple pawl mechanism to stabilise the geometry after shaping. Finally, C1 served to demonstrate the implementation of variable curvature, leveraging natural material variability as both a design driver and a means for more sustainable material utilisation.

4.1 Unfurling and expanding flat-pack chair (Case study 1: H1)

Case study H1 served as a primary demonstrator for the self-shaping capability of wood in a furniture application, focusing on a lounge chair designed for a dramatic volumetric transformation from a compact flat-pack.

Material: The prototype was fabricated from high-quality, radial cut European maple wood, sourced in the state of Baden-Württemberg. The active layer was prepared to operate within a WMC range from the fibre saturation point of 30% down to an average of 10.2% (equilibrium at typical indoor conditions), as previously detailed in Chapter 3.

Design Process: The primary design objective for H1 was to achieve a significant change in bounding box volume. The furniture piece was conceived as a highly compact flat-pack, with the outlines of both layers largely overlapping in the initial flat configuration (Figure 5). Upon actuation, it was designed to unfold into an upright lounge chair, exhibiting a distinct curling and expansive geometry (Figure 5 c). Detailing of the feet was specifically incorporated to ensure stable and intentional support in the final shaped state.

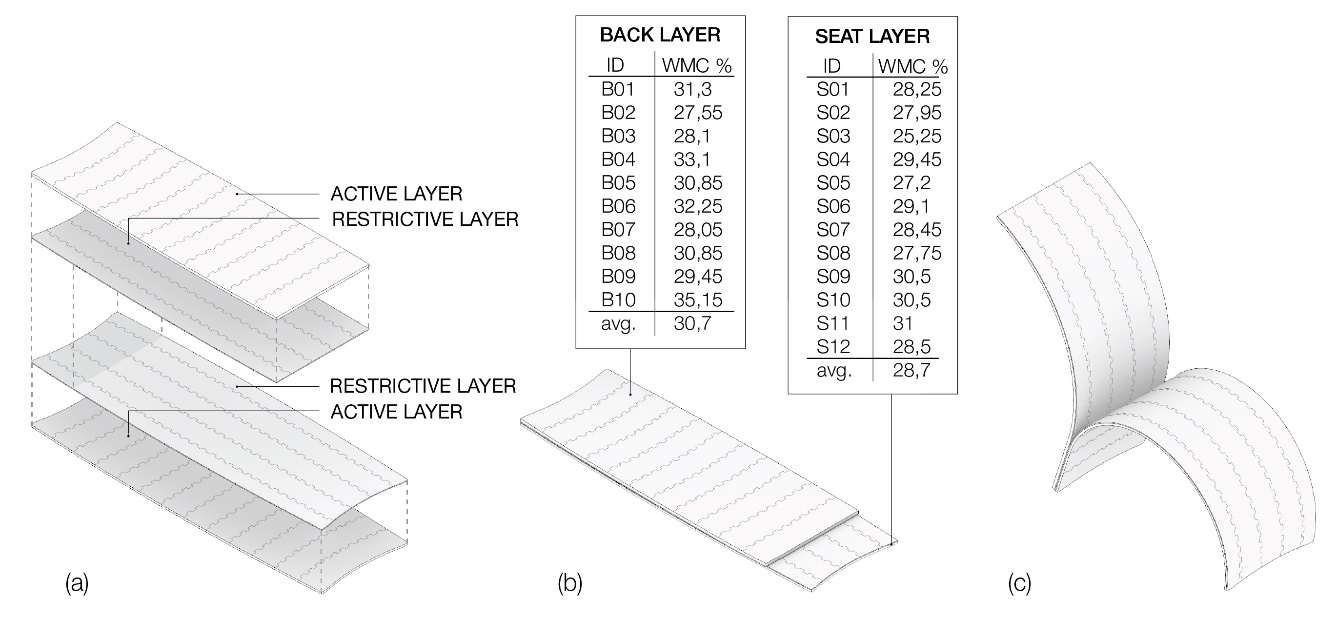

Bilayer Design: The H1 prototype comprised two separate bilayers: a seat layer and a back layer, which were joined together in a flat, ‘inactive’ bilayer segment (Figure 5 c). This design explicitly aimed to showcase two distinctly different curvatures in opposing directions within a single piece. Both layers were designed to undergo the same WMC delta, from a starting point of approximately 25% to a target end state of 10%. However, they featured different total bilayer thicknesses: the seat layer was 11 mm thick, while the back layer was 14 mm thick.

Fabrication: The seat layer was fabricated from an 8 mm thick active and a 3 mm thick restrictive layer. The backrest, conversely, comprised an 11 mm thick active and a 3 mm thick restrictive layer (Figure 5 a). The active layers were equalised at 95% RH to achieve a WMC of above 25%, accounting for potential moisture losses during the subsequent fabrication steps (Figure 5 b). The WMC was monitored in regular intervals with a handheld moisture meter (Brookhuis FMW). The bilayers were then CNC cut, bonded, and trimmed to their final outlines. The flat chair segments were finally planed and sanded.

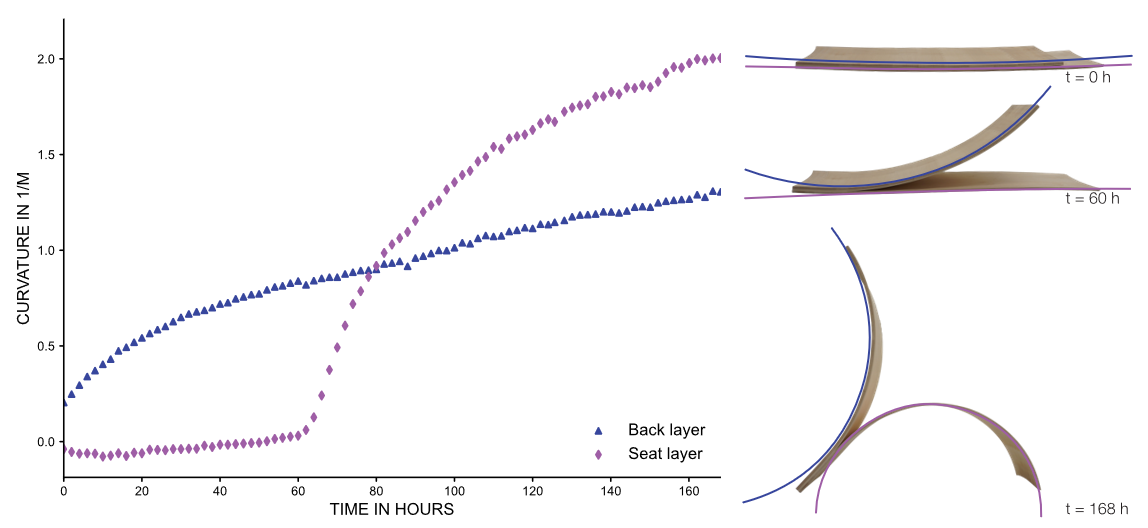

Self-shaping and geometric data acquisition: The majority of the shape change occurred over a period of approximately seven days. A set of 85 frames, with a two-hour time step between each, was selected for analysing the curvature. Ten points were placed manually on each frame in Fiji; half of these were located on the back layer and half on the seat layer, at regular distances (corresponding to two active layer boards).

Within the Rhino/Grasshopper environment, a circle was fitted to the points of both the back and seat layers using an algebraic fit. From these two circles, the curvature development over the seven-day self-shaping process was evaluated (Figure 6). The back layer began curving as soon as it was exposed to environmental conditions. Within the first 30-40 hours, the fastest shaping occurred. Afterwards, it continued almost linearly and slowed down slightly, progressing towards a curvature of 1.3 1/m (or a radius of 770 mm).

The seat layer initially exhibited a reverse (negative) curvature due to its storage in a high RH environment and slight spraying with water during setup. It only began curving in the designed direction after approximately 50 hours. This was attributed to the layer being placed flat on the ground (a non-porous polycarbonate surface) and thus not fully exposed to air. In the timeframe between 60 and 130 hours, it shaped extraordinarily fast, slowing down as it approached a curvature of around 2 1/m (which corresponded to a radius of 500 mm). Once it was exposed to air, the thinner seat layer shaped more quickly, as was expected with a smaller cross-section (indicating quicker desorption of moisture). While the prototype continued shaping further after the seven days of recording, it had already reached a functional geometry that was within the planned design range.

Evaluation of the method and design: This first demonstrator successfully showed that self-shaping wood could be used to create curved furniture that actuated reliably at ambient indoor conditions (Figure 7). It served as a crucial proof-of-concept for both the developed computational workflow and the fabrication method. From a design perspective, the combination of different radii was successfully tested, yielding an extreme change in bounding box volume, with a volume increase of 25 times and reaching a final height of 980 mm. The prototype exhibited some compliance, with the grain direction in the bilayers oriented for shaping rather than for structural stability. One key takeaway from the shaping process was that the shaping sequence could be choreographed through intentional exposure or coverage of parts.

4.2 Curvature transitions and pawl mechanism in a flat-pack chaise lounge (Case study 2: H2)

Case study H2 focused on achieving a more complex S-shaped geometry, exploring the controlled transition between opposing curvatures within a single furniture element.

Material: The prototype was fabricated using the same high-quality, rift-cut European maple wood as employed for Case Study H1.

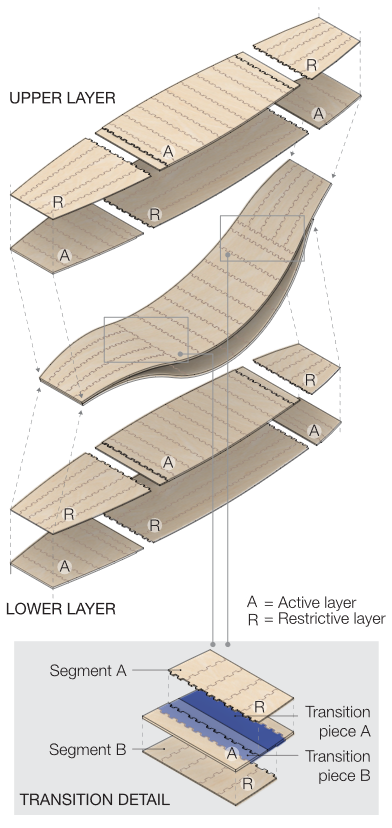

Design Process: The objective for H2 was to create a lounge chair featuring a smooth transition between two opposing curvatures, forming a sophisticated S-shape. The upper curvature was designed to conform to the shape of the body, while the lower curvature functioned to elevate the sitting layer from the ground. The lower layer was configured to exhibit a higher curvature than the upper one. The curvature and outline cuts of the two layers were adjusted to ensure the lounge chair intentionally balanced on the arch of the lower layer. The outline bulged slightly in the middle, corresponding to the intended centre of gravity, and tapered towards both ends. The two layers were connected at the foot of the chair, where their outlines were identical. From this foot connection onward, the outline of each layer was detailed to ensure a precise match in the final curved state. During the shaping process, the lower layer, was intended to slide along the underside of the upper layer until it engaged a simple pawl mechanism, which subsequently stabilised the geometry when the seat was loaded or when ambient conditions fluctuated. This configuration necessitated a transition from a positive to a negative curvature, requiring a switch in the relative location of the active and passive layers. A specific transition detail (Figure 8) enabled this, wherein two active layer segments included a milled pocket for the opposing passive layer.

Bilayer Design: The H2 prototype incorporated two different bilayer buildups within its two main layers, maintaining a constant total thickness of 13 mm for both. The lower layer, designed for a higher curvature, comprised a 4 mm thick restrictive layer and a 9 mm thick active layer. The upper layer featured a 5 mm thick restrictive layer and an 8 mm thick active layer. To emphasise the distinct curvatures in both layers, a different WMC delta was targeted: the upper layer was planned to have a starting WMC of 22.5%, while the lower layer commenced with a WMC of 18%. Both layers were planned to dry to approximately 10% WMC in ambient conditions similar to those for H1.

Fabrication: Both layers were manufactured flat from boards that had been equalised in a 90% RH environment. For the targeted different starting WMCs, boards with lower WMCs from the material stock were selected for the upper layer, while those with higher WMCs were used for the lower layer. The three segments of each layer were glued together with the designated transition pieces in one lamination step. A simple pawl mechanism was detailed to allow the two layers to interlock after shaping. Prior to actuation, the two layers were glued together at the foot end of the prototype.

Self-shaping and geometric data acquisition: The self-shaping process was recorded over a period of seven days, during which the majority of the shape change occurred. A set of 164 images was evaluated, with one-hour time steps between each. Within the first 2 days the data set exhibits some gaps due to camera failure, the longest of which spans over 5 hours. Nineteen points were placed in Fiji on each frame: thirteen in the upper layer and six in the lower layer.

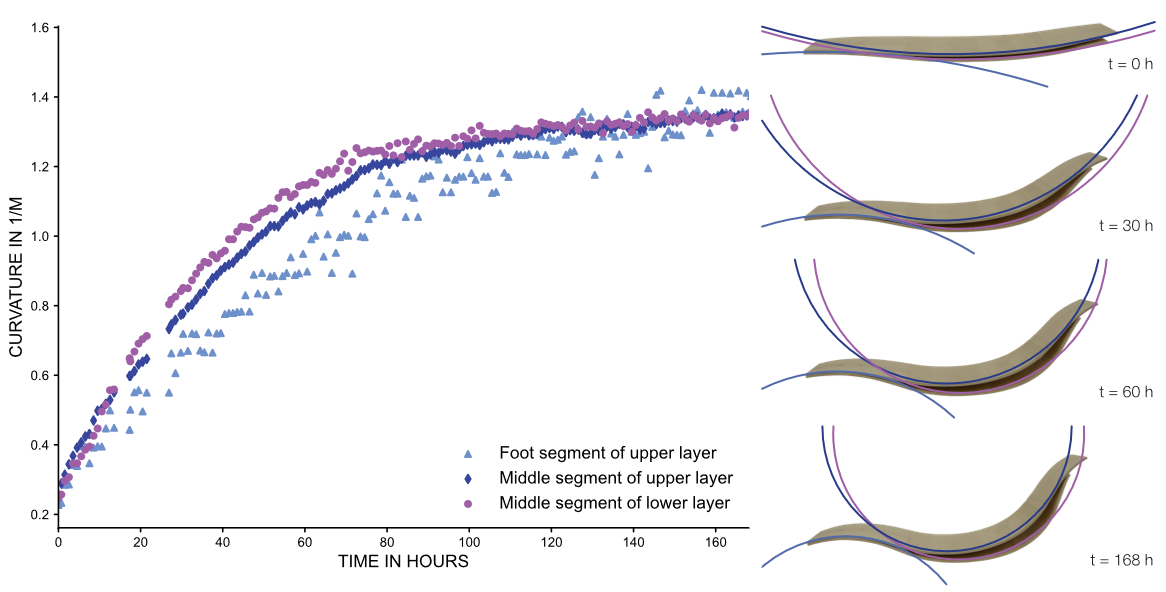

In the Rhino/Grasshopper environment, circles were fitted through the points using an algebraic fit. Segments that were too short to yield reliable results were omitted; instead, circles were fitted through the middle segment of both the upper and the lower layer, which were sufficiently long to provide reliable data. In the upper layer, circles were also fitted through the foot segment. Figure 9 illustrates the curvature development over the seven-day duration.

At the beginning of the recording, both layers already exhibited a slight curvature, hence the shaping did not commence from zero curvature. In the first 13 hours, the middle segment of the upper layer shaped slightly faster than its counterpart in the lower layer. This was likely due to better exposure to air, which accelerated the desorption process. However, in this case, the lower layer's actuation was not as significantly delayed by reduced air circulation in comparison to H1, as the active layer faced upwards, and a slight initial curvature already enabled some air circulation between the layers.

After approximately 13 hours, the thinner lower layer began to shape faster. After around 70 hours, at a curvature of roughly 1.25 1/m (or a radius of 800 mm), the speed of shaping in the lower layer reduced. The reason for this could be that the resistance of the lower layer pushing against the upper one from below became too high, inhibiting further shaping. At roughly 115 hours, the curvatures in the middle segment of both layers reached similar values, which persisted until the end of the recording.

Evaluation of the method and design: This case study successfully showcased how a continuous element with a transitioning curvature could be realised. From a design perspective, the double-layered buildup with different radii enabled a higher level of sophistication and resulted in an aesthetically pleasing form (Figure 10). The interplay of the two layers allowed for the integration of a simple pawl mechanism, which added structural stability when the chair was loaded, as well as form stability under slightly varying ambient conditions. Regarding the shaping process, it was observed that the self-weight and interaction of both layers had a significant impact on the shaping, a factor not explicitly considered in the Timoshenko computation of the expected curvatures. Concerns that the lower layer would be inhibited from shaping due to being covered by the upper layer proved unnecessary. The use of different WMC deltas caused more effort in the preparation of the material (necessitating a larger material stock to select boards with higher or lower WMCs for the respective layers). This also led to the prototype not being completely flat at the beginning of the shaping process. A key takeaway was that for efficient flat-pack transport, a uniform WMC delta is beneficial.

4.3 Natural variability in a single log, flat-pack lounger (Case study 3: C1)

C1 explored the integration of natural material variability into the design and fabrication process, aiming for a more sustainable utilisation of wood resources.

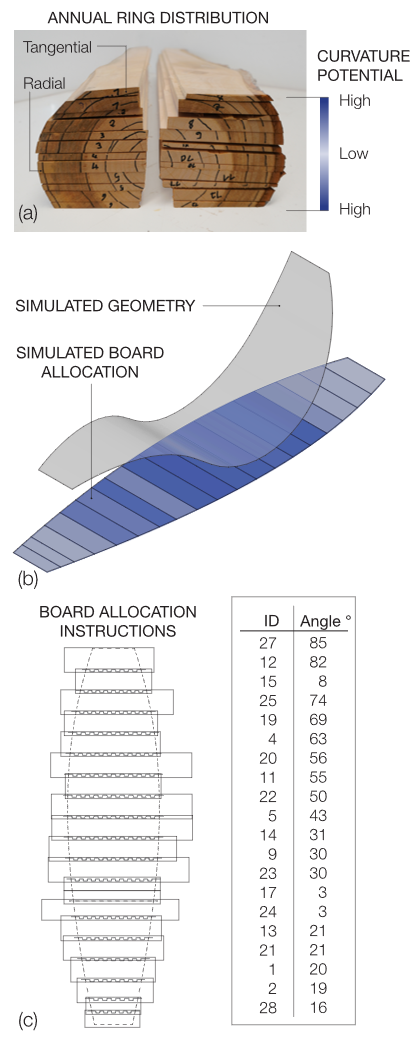

Material: The material for this prototype was sourced from a section of a single wild cherry tree, an older tree that had begun to rot internally. This material was part of the ‘Slowwood’ initiative, a collaborative effort dedicated to showcasing diverse uses for timber derived from a single tree. The total stock comprised 28 boards, exhibiting variable widths and, critically, a range of annual ring angles (Figure 11 a). This inherent variability in annual ring inclination significantly influences the moisture-related swelling and shrinking behaviour of individual boards. The entire stock was carefully catalogued and documented, including any natural defects. To make optimal use of the limited stock and based on the availability of specific annual ring angles, some boards were split into two thinner thicknesses to serve as passive layers.

Design process: The primary design objective was to develop a form that maximally utilised the diverse material properties present in the varied stock. For each board in the stock pile, its individual curvature potential was computed, serving as a direct input for the design (Figure 11 b). The aim was to exploit the full range of possible curvatures. The resulting form was an S-shape with a single curvature transition, characterised by a gradient where the curvature became less pronounced towards the ends of the prototype and most extreme at the lowest point of the shape.

Bilayer design: The bilayer configuration featured a total height of 11 mm, with an active layer of 9 mm and a restrictive layer of 2 mm. The target starting WMC was 25%, aiming for an end WMC of 9%, corresponding to an RH of slightly above 40%. The annual ring angle was designed to change gradually throughout the length of the lounge chair. Specifically, the most tangential active layer boards were placed in the central sections of the prototype, where extreme curvature was desired, while the most radial active layer boards, which yield a more subtle curvature, were positioned towards the ends. The precise arrangement of the boards and the resulting shape was designed through a combination of manual arrangements of the board parameters into the shape matching model and sorting the boards to form smooth gradients.

Fabrication: Boards were equalised in a 95% RH environment. Initially, boards were planed to a thickness 2 mm greater than the final bilayer configuration. Based on the specific board allocations, the boards were CNC cut, bonded, and trimmed to their final outline (Figure 11 c). To achieve a smooth and clean surface, the flat chair component was face milled from both sides to the designed thickness. Due to the high WMC delta and the inherent variability in the material, some deformation already occurred on the milling bed, resulting in uneven final thicknesses in certain areas.

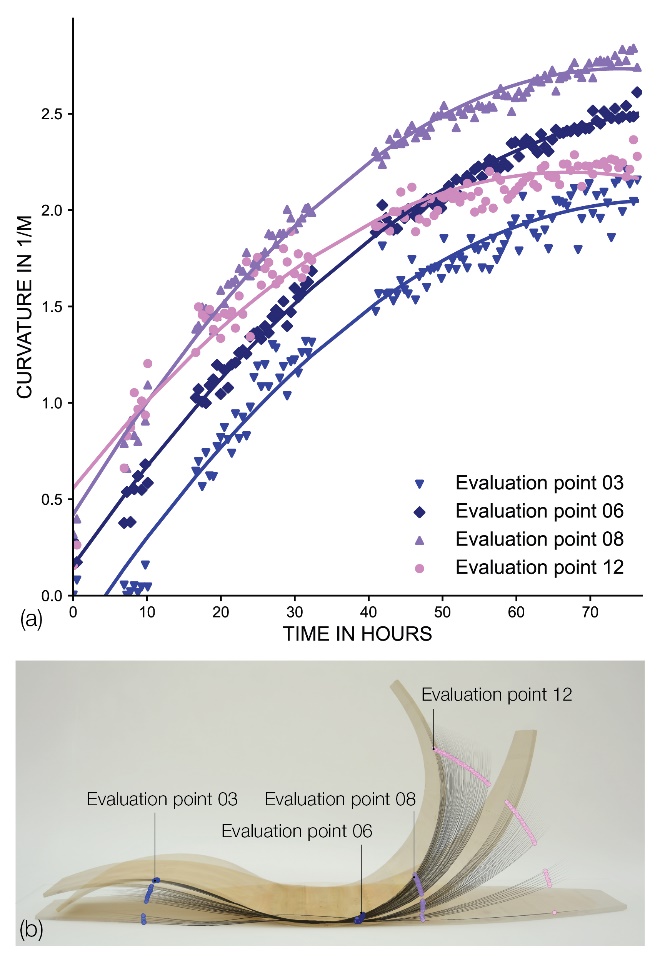

Self-shaping and geometric data acquisition: The self-shaping process was recorded over a period of 77 hours. A set of 115 frames was analysed, with 30-minute time steps between each. Although several camera failures occurred during this period, including one spanning over 8 hours and 40 minutes, the available data allowed for comprehensive analysis. Ten points were placed at regular distances on the edge of the active layer in Fiji.

Given that the curvature was designed with a gradient, a curve rather than a simple circle was fitted through these points. Within the Rhino/Grasshopper environment, a parametric spline interpolation was employed to generate a smooth curve through the collected points. To minimise local irregularities and ensure a geometrically coherent representation, this interpolated curve was subsequently approximated using a degree-3 curve fitting method. We placed 12 evaluation points along the curve at 100 mm intervals, deliberately omitting the inflection point where the curvature approached zero. From the set of evaluation points, six exemplary points were selected for an absolute curvature visualisation (Figure 12). For each point on the self-shaping prototype, the evolution of curvature over time was approximated using a second-degree polynomial regression. The fitting was performed using a least-squares approach, yielding smooth, continuous functions.

As the prototype did not start completely flat, the initial curvature values did not commence at 0. As expected, evaluation points 6 and 8, located in the centre of the prototype, reached the highest curvature values. Point 12, at the head end of the chair, began with a relatively high curvature compared to the other evaluation points. However, after approximately 40 hours, its curvature fell behind both points 6 and 8, finishing with a curvature of around 2.3 1/m (or a radius of 435 mm). The rapid initial shaping might have been due to the evaluation point's location being close to the head end of the chair, where the impact of self-weight was minimal.

Evaluation of the method and design: With this prototype, it was successfully demonstrated that natural variations in wood could be utilised to inform a design with variable curvature (Figure 13). This method proved suitable for small, low-grade, variable stock, such as offcuts or leftover material. However, the case study also highlighted limitations and difficulties associated with low-grade wood possessing highly heterogeneous material properties. A higher degree of sorting and stock management was necessary. Furthermore, processing the prototype in its flat state proved challenging due to the material's rapid and strong deformation.

5 Conclusion

This study presents the novel concept of self-shaping wood furniture, driven by the natural hygromorphic properties of wood to actuate passively when exposed to regular indoor conditions. Our method enables a simplified 2D fabrication, using standard wood processing machinery enabling a flat-pack transportation and autonomous shaping—without the need for mechanical actuation, or complex manual assembly.

The proposed computational workflow begins with material-specific parameters and curvature prediction, continues through flat-state design, and concludes with digital fabrication and self-shaping actuation. This workflow was tested on three distinct prototypes. Case Study 1 demonstrated a dramatic increase in bounding volume through combined radii and confirmed the reliability of the system under typical indoor conditions. Case Study 2 explored a smooth transition between opposing curvatures and the integration of a locking mechanism, and highlighted the impact of multi-part interaction and self-weight effects. Case Study 3 investigated natural material variability as a design driver and points toward a more holistic and resource-efficient use of wood.

Looking ahead, three major areas of future work are evident. First, the curvature development in all prototypes indicates that shaping continues beyond the initial actuation period, influenced also by seasonal ambient fluctuations as became visible through qualitative observations of the prototypes over time. This necessitates further investigation into long-term form stability and potential locking mechanisms, especially for load-bearing applications. Second, further refinement of the design and simulation workflow is required: in complex assemblies, simulation methods must capture self-weight, material interaction, and friction. Beyond supporting inverse design, a more comprehensive tool could also enable more intuitive forward design exploration. Third, progressing toward real-world implementation will require quantitative structural assessment. On a larger scale, this research opens up possibilities for real-time material-driven design, where curvature is informed by digital inventories derived from board or log scanning, including annual ring angle, defects, and current WMC. Such a workflow could enable designs to directly respond to the material's condition post-harvest, using elevated WMC stock that only slightly dries during transport or storage.

This work contributes to the fields of material programming, deployable furniture systems, and digital fabrication with natural materials, and lays the groundwork for further integration of shape-changing behavior in interior environments.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by the internal funding of the university of Stuttgart for knowledge and technology transfer and by the agency for Renewable Resources (FNR) under the number 2221HV096C as well as the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) as part of Germany's Excellence Strategy - EXC 2120/1-390831618. We would like to thank our project partners, namely Prof. Markus Rüggeberg for their expertise and advice as well as the Slowwood initiative for providing material and Baumustercentrale Zürich for exhibiting our prototype. We also wish to thank Kristina Schramm, Lena Strobel, Amrutha Tattamangalam Vaidyanathan, Lasath Siriwardena, Michael Schneider, and Michael Preisack for their technical assistance and support, and Robert Faulkner for his skillful photographic and videographic documentation. The authors disclose that this research is the subject of European Patent EP20216959.5. In addition, some authors are founders of the spin-off company Hylo Tech, which seeks to commercialize this technology.

References

- Zuardin Akbar, Dylan Wood, Laura Kiesewetter, Achim Menges, and Thomas Wortmann. 2022. “A Data-Driven Workflow for Modelling Self-Shaping Wood Bilayer, Utilizing Natural Material Variations with Machine Vision and Machine Learning.” 393–402. https://doi.org/10.52842/conf.caadria.2022.1.393.

- Lotte Aldinger, Georgia Margariti, Axel Körner, Seiichi Suzuki, and Jan Knippers. 2018. “Tailoring Self-Formation Fabrication and Simulation of Membrane-Actuated Stiffness Gradient Composites.” Proceedings of the IASS Symposium 2018: Creativity in Structural Design 141 (July).

- Martin Alvarez, David Stieler, Laura Kiesewetter, et al. 2025. “INNOVATIVE SELF-SHAPING TIMBER CONSTRUCTION: THE WANGEN TOWER.” World Conference on Timber Engineering 2025, 863–72. https://doi.org/10.52202/080513-0108.

- Sofien Bouaziz, Mario Deuss, Yuliy Schwartzburg, Thibaut Weise, and Mark Pauly. 2012. “Shape‐Up: Shaping Discrete Geometry with Projections.” Computer Graphics Forum 31 (5): 1657–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8659.2012.03171.x.

- Ben Bridgens, Artem Holstov, and Graham Farmer. 2017. Architectural Application of Wood Based Responsive Building Skins.

- CEN. 2019. EN 16798-1:2019. Energy Performance of Buildings – Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics – Module M1-6. European Standard EN 16798-1:2019. https://standards.cen.eu.

- Tiffany Cheng, Yasaman Tahouni, Ekin Sahin, et al. 2024. “Weather-Responsive Adaptive Shading through Biobased and Bioinspired Hygromorphic 4D-Printing.” Nature Communications 15 (November). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54808-8.

- Tiffany Cheng, Marc Thielen, Simon Poppinga, et al. 2021. “Bio‐Inspired Motion Mechanisms: Computational Design and Material Programming of Self‐Adjusting 4D‐Printed Wearable Systems.” Advanced Science 8 (13). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202100411.

- Tiffany Cheng, Dylan Wood, Laura Kiesewetter, Eda Özdemir, Karen Antorveza, and Achim Menges. 2021. “Programming Material Compliance and Actuation: Hybrid Additive Fabrication of Biocomposite Structures for Large-Scale Self-Shaping.” Bioinspiration & Biomimetics 16 (5): 055004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/ac10af.

- Colin Dawson, Julian F. V. Vincent, and Anne-Marie Rocca. 1997. “How Pine Cones Open.” Nature 390 (6661): 668–668. https://doi.org/10.1038/37745.

- ECAL. 2024. “Under Pressure Solutions.” Exhibition for the 2024 Milano Design Week. https://underpressuresolutions.ch/.

- Philippe Grönquist, Falk K. Wittel, and Markus Rüggeberg. 2018. “Modeling and Design of Thin Bending Wooden Bilayers.” PLOS ONE 13 (10): e0205607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205607.

- R Bruce Hoadley. 2017. Understanding Wood: A Craftsman's Guide to Wood Technology. Completely revised and Updated. Taunton Press.

- Haruto Kamijo, and Tomohiro Tachi. 2024. “Curvature Design of Programmable Textile.” Proceedings of the 9th ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication, July 7, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1145/3639473.3665789.

- Dharshika Kongahage, and Javad Foroughi. 2019. “Actuator Materials: Review on Recent Advances and Future Outlook for Smart Textiles.” Fibers 7 (3): 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib7030021.

- Eda Özdemir, Laura Kiesewetter, Karen Antorveza, Tiffany Cheng, Dylan Wood, and Achim Menges. 2022. “Towards Self-Shaping Metamaterial Shells: A Computational Design Workflow for Hybrid Additive Manufacturing of Architectural Scale Double-Curved Structures.” Proceedings of the 2021 DigitalFUTURES (Singapore), 275–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5983-6_26.

- Daniel Piker. 2013. “Kangaroo: Form Finding with Computational Physics.” Architectural Design 83 (2): 136–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.1569.

- E Reyssat, and L Mahadevan. 2009. “Hygromorphs: From Pine Cones to Biomimetic Bilayers.” Journal of The Royal Society Interface 6 (39): 951–57. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2009.0184.

- Jan Rijsdijk, and Peter Laming. 1994. Physical and Related Properties of 145 Timbers Information for practice. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-8364-0.

- Robert Ross. 2021. Wood Handbook—Wood as an Engineering Material. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory.

- Markus Rüggeberg, and Ingo Burgert. 2015. “Bio-Inspired Wooden Actuators for Large Scale Applications.” PLOS ONE 10 (4): e0120718. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120718.

- Roozmehr Safi. 2022. “What Consumers Think about Product Self-Assembly: Insights from Big Data.” Journal of Business Research 153 (December): 341–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.08.003.

- Johannes Schindelin, Ignacio Arganda-Carreras, Erwin Frise, et al. 2012. “Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis.” Nature Methods 9 (7): 676–82. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019.

- Skylar Tibbits, Athina Papadopoulou, Carrie McKnelly, et al. 2015. “Programmable Table.” https://selfassemblylab.mit.edu/programmable-table/.

- Walter Sonderegger, Anne Martienssen, Christiane Nitsche, Tomasz Ozyhar, Michael Kaliske, and Peter Niemz. 2013. “Investigations on the Physical and Mechanical Behaviour of Sycamore Maple (Acer Pseudoplatanus L.).” European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 71 (1): 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-012-0641-8.

- Tom Svilans, and Mette Ramsgaard Thomsen. 2024. “Drawing a Blank – Design Modelling Composite Timber Elements.” Architectural Intelligence 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44223-024-00048-1.

- Yasaman Tahouni, Tiffany Cheng, Dylan Wood, et al. 2020. “Self-Shaping Curved Folding: A 4D-Printing Method for Fabrication of Self-Folding Curved Crease Structures.” Symposium on Computational Fabrication, November 5, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1145/3424630.3425416.

- Kenryo Takahashi, Laura Kiesewetter, Axel Körner, Dylan Wood, Jan Knippers, and Achim Menges. 2024. “Structural Design and Construction of a Self-Shaping Single Curved Timber Structure HygroShell.” Paper presented at IASS 2024, Zürich. Proceedings of the IASS 2024 Symposium, August 26.

- Stepan Timoshenko. 1925. Analysis of Bi-Metal Thermostats. November 9.

- Guanyun Wang, Humphrey Yang, Zeyu Yan, et al. 2018. “4DMesh: 4D Printing Morphing Non-Developable Mesh Surfaces.” Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, October 11, 623–35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3242587.3242625.

- Wen Wang, Lining Yao, Teng Zhang, Chin-Yi Cheng, Daniel Levine, and Hiroshi Ishii. 2017. “Transformative Appetite: Shape-Changing Food Transforms from 2D to 3D by Water Interaction through Cooking.” Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2, 6123–32. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3026019.

- Dylan Wood, Chiara Vailati, Achim Menges, and Markus Rüggeberg. 2018. “Hygroscopically Actuated Wood Elements for Weather Responsive and Self-Forming Building Parts – Facilitating Upscaling and Complex Shape Changes.” Construction and Building Materials 165 (March): 782–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.134.

- Dylan Wood, Philippe Grönquist, Simon Bechert, et al. 2020. From Machine Control to Material Programming: Self-Shaping Wood Manufacturing of a High Performance Curved CLT Structure – Urbach Tower. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv13xpsvw.11.

- Dylan Wood, Laura Kiesewetter, Axel Körner, Kenryo Takahashi, Jan Knippers, and Achim Menges. 2023. “HYGROSHELL – In Situ Self-Shaping of Curved Timber Shells.” In Advances in Architectural Geometry 2023, edited by Kathrin Dörfler, Jan Knippers, Achim Menges, Stefana Parascho, Helmut Pottmann, and Thomas Wortmann. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111162683-004.

- Raymond Young. 2007. Wood and Wood Products. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-27843-8_28.

- Juan Zambrano-Jaramillo, Erica Fischer, and Dylan Wood. 2024. Geometry, Material, and Structural Exploration for Curved Cross- Laminated Timber Structures.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

SCF '25, Cambridge, USA

© 2025 Copyright held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 979-8-4007-2034-5/2025/11

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3745778.3766658